Between the 1020s and 1200, one of the most important pilgrimage routes to the Holy Land went through Hungary. It was a popular one, since making the long journey on sea was considered a lot more dangerous than walking, with ‘pericula maris’ (the perils of the sea) spoken of in terror. The opening of the pilgrimage route also had an outstandingly positive impact on the reputation of medieval Hungary.

Contemporary chronicler Rudolphus Glaber highlighted the opening of the new route in his work. However, he failed to mention that, aside from the Christianisation of the country by Stephen I (ruled 997/1000–1038), what was also necessary for that to happen had been the pacification of territories on the other side of the Southern border of Hungary by Byzantine emperor Basil II the Bulgar Slayer.

It would be tempting to think that the pilgrims were aware of the holy sites and saints of the Carpathian Base of the past centuries, such as St Martin and Quirinus in Szombathely (Savaria), St Hadrianus in Zalavár near Lake Balaton, or St Irenaeus and St Demetrius in Sirmium (today Sremska Mitrovica, Serbia). However, that was hardly the case. Rather, this was a brand new phenomenon.

Since the destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre by Fatimid Caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr (996–1021) in 1009, the attention of Christendom had been concentrated on the Holy Land, and the tumultuous fate of the holy sites was also followed with great interest.

The 1,000th anniversary of the Passion of Christ was an event of outstanding significance in that century,

as also mentioned by Glaber. Indeed, large masses set out for the Holy Land in 1033. The 11th century brought a huge uptick in the number of pilgrimages. While a total of 22 journeys to the Holy Land were recorded between 870 and 1026, this number multiplied many times over by the end of the century. However, because of their abundance, the exact number of pilgrimages is hard to determine with any confidence.

During the First Crusade, it was surprising how smoothly the provision of supplies for the thousands of crusaders marching through Hungary went.

In actuality, there was already half a century of experience behind the supplying of the crusaders traversing the country, something that had been being perfected since the pilgrimage route opened under the reign of St Stephen.

As the circumstances of the time dictated, the pilgrims travelled in groups and larger masses, since this was the only way to have any chance of fulfilling their vow. This is what Aryeh Grabois refers to as ‘la collectivisation du pélerinage’, where the personal atonement for one’s sins becomes a collective experience. It did seem like a reasonable solution for the travellers to join the company of a noble or a high clergyman, who could provide a certain level of protection regarding the safety of their person and their belongings.

The most important source we have is the chapters about the pilgrimage of William, Count of Angoulême (987–1028), written by French chronicler Adémar de Chabannes, from the years 1026–1027. Adémar himself embarked on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land across Hungary later, in 1033. The most notable pilgrim was the abbot of Verdun, Richard of Saint Venne (†1046), later venerated as a saint, who was received by both Emperor Constantine VII and the Patriarch in Constantinople. Richard was also gifted a fragment of the True Cross, which remained the cherished relic of the Monastery of Verdun for centuries. A direct link to Hungary is that St Gerard (Gellért) of Csanád, Bishop of Hungary (+1046), may have been in contact with him, as in Gerard’s surviving Latin-language work Deliberatio he mentions an Abbot Richard, who was likely the same person as Richard of Verdun[1].

Gerard is likely to have been one of the earliest pilgrims venturing to Hungary

since, according to his legend, he interrupted his pilgrimage from Venice and settled in Hungary on the request of King St Stephen. This holy expedition may have played a role in some of the clergymen of Verdun resettling in Hungary in the mid-11th century. What’s more, these pilgrimages may even have been the main source of information about Hungary for Western people.

The great pilgrimage of 1064–65, led by Gunther, Bishop of Bamberg (1057–1065),[2] stands far out among those in the 11th century. A rare astronomical alignment occurred for the first time in the century in 1065. The celebration of the resurrection of Christ fell on 27 March that year, almost coinciding with the Feast of Annunciation on 25 March.[3]

The group—or rather, army, since the sources speak of thousands of people taking part—of pilgrims included the Archbishop of Mainz, the Bishop of Utrecht, the Chaplain of the German Imperial Court, and many other, high-ranking clergymen, mainly from Southern Germany.

Gunther met his demise on his way back home, near the Hungarian border. His fellow pilgrims took his corpse back to Bamberg, where his tomb still stands to this day, and a large piece of Byzantine textile, ‘Gunther’s shroud’, can also be found in it to this day. He most likely got it as a gift from the Byzantine Emperor. This is backed up by the fact that German Emperor Henry IV had sent letters to the King of Hungary and the Byzantine Emperor with Gunther, thus we can be certain of his coming into contact with these courts.

The merging of pilgrimages and diplomatic missions was not uncommon at the time.

The Bishop wore his ornate piece of cloth on his pilgrimage too, which may have made him the target of robbers.[4]

Aside from Gunther, another notable figure of the pilgrims was Lambert of Hersfeld, a Franconian historian who had written about the Hun–Hungarian tradition in his works. He had made his journey to the Holy Land across Hungary years prior, in 1058. He wrote his chronicle, an almanack a long time after, relying on the experiences he accumulated through his journey.

Of all the pilgrimages, the English ones have been researched the most. The first group of pilgrims from England arrived in the 1050s, led by Ealdred, Bishop of Worcester (+1069), who later became the Archbishop of York. His pilgrimage across Hungary can be confidently dated to 1058.[5] From the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, we can learn that he gifted an invaluable grail to the Holy Sepulchre.[6] Whatever the case might be, the seal of Sophronius II, Patriarch of Jerusalem was found in Winchester, which is further evidence of his pilgrimage’s success.

The significance pilgrimages had in terms of building clerical and diplomatic relations cannot be overlooked either.

A whole slew of abbots, bishops, future archbishops, historians, poets, theological thinkers, and monks later canonised as saints visited Hungary.

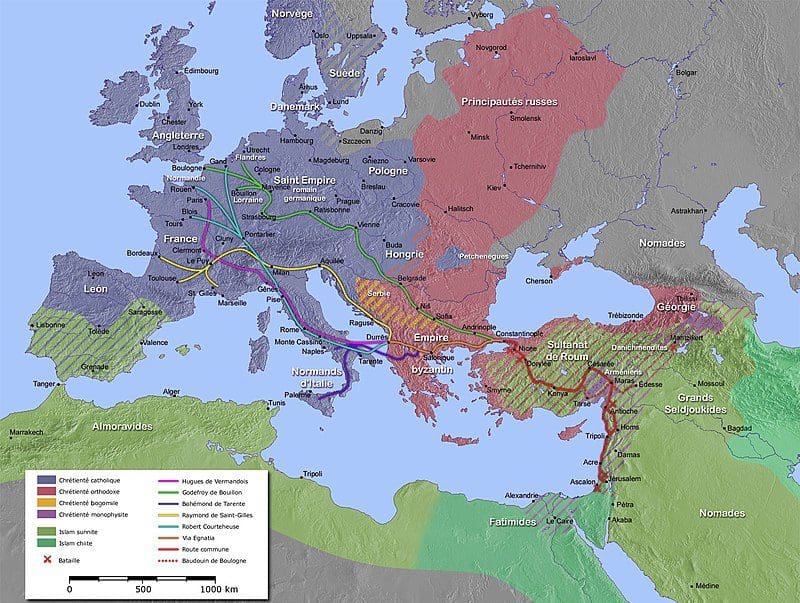

They brought highly cherished relics, luxury items of the East, and—not least—news with them. During the time of the Crusades, archdukes, kings, and queens traversed Hungary: the first ruler of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, Godfrey of Bouillon did so in 1096, Kings Conrad III, Louis VII with Eleanor of Aquitaine in 1046, and Emperor Barbarossa in 1089.

The intensity of the pilgrimages played an important role in the organic development of the crusading ideal in 11th century. Many contemporary historians, including Riley-Smith and Matthew Gabrielle, believe that the immense popularity of the idea of the crusades was the consequence of the Jerusalem tradition[7], which had already been present for decades at the time. All this convincingly refutes the opinion of some of the orthodox byzantologists that the crusades were the ad hoc decisions by popes, and the result of their condemnable, devilish scheming.

[1] Előd Nemerkényi, Latin Classics in Medieval Hungary: Eleventh Century, Debrecen – Budapest, 2004, pp. 74, 145.

[2] Carl Erdmann, ‘Gunther von Bamberg als Heldendichter’. Zeitschrift für deutsches Altertum und Literatur 74 (1937), p. 116.; David Jacoby, ‘Bishop Gunther of Bamberg. Byzantium and Christian Pilgrimage to the Holy Land in the Eleventh Century’, in Lars Hoffmann (ed.), Zwischen Polis, Provinz und Peripherie. Mainzer Veröffentlichungen zur Byzantinistik vol. 7, Wiesbaden, 2005, pp. 267–285.

[3] Rachel Fulton, From Judgment to Passion: Devotion to Christ and the Virgin Mary, 800-1200, New York, 2003, pp. 77–78.

[4] Jonathan Riley–Smith, The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading, Cambridge, 1997, p. 39.

[5] Frank Barlow, Edward the Confessor, Berkeley, CA, 1970, pp. 208–209

[6] The Anglo-Saxon chronicle, (trans.) G. N. Garmonsway, London-Toronto, 1975, 189.

[7] Matthew Gabriele, An Empire of Memory: The Legend of Charlemagne, the Franks, and Jerusalem before the First Crusade, New York, 2011, pp. 79–93.

Related articles: