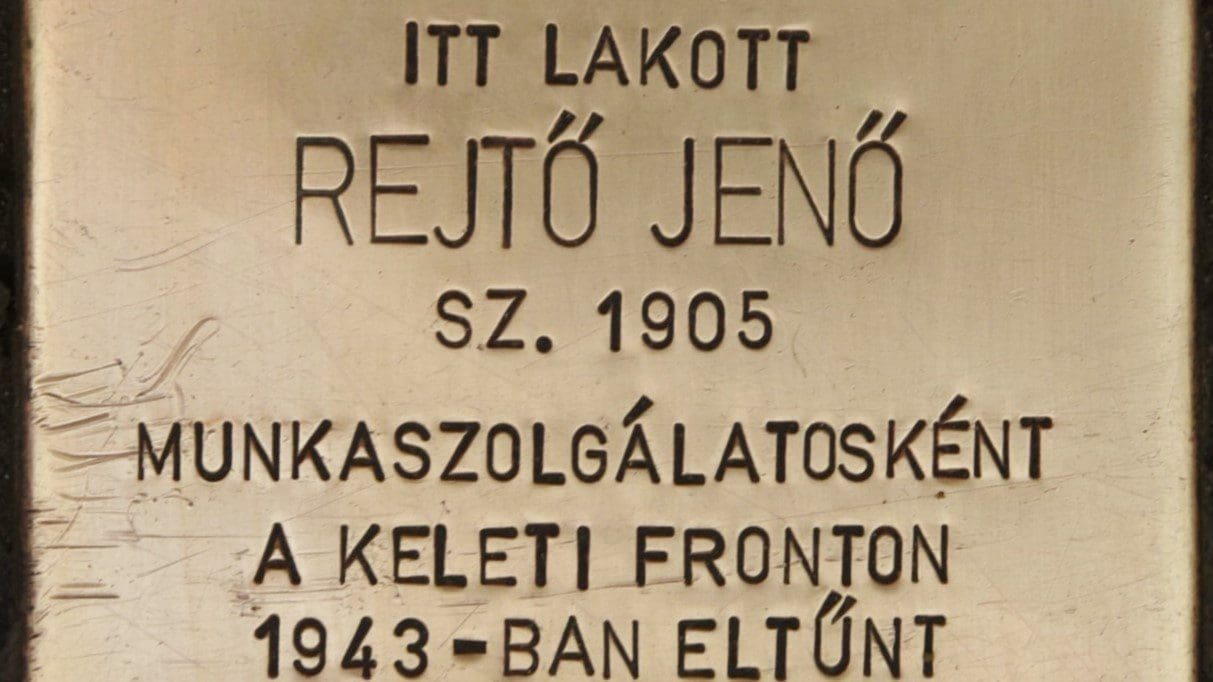

‘There are a lot of stories about Jenő Rejtő, but most of them are not supported by facts—he has no biography, so to speak, only a collection of legends. (…) Since little is known about his life, his readers remedied this shortcoming in their own way: they created all kinds of myths and tales, thus producing a non-canonized, constantly evolving, alternative biography.’[i] These are the opening lines of the 2016 volume of essays entitled The Tragedy Uncovered —In Memory of Jenő Rejtő, edited by Gergely Thuróczy. Although there is perhaps little to add to the words cited above, not long after the presumed anniversary of the death of the eminent quality pulp fiction writer, who published most of his work under the alias P. Howard, it is worth going through the facts and legends known about Rejtő’s last days. The great Jewish Hungarian author, born Jenő Reich, who has been extensively translated to English and other European languages, shared the tragic fate of many Hungarians of Jewish extraction in WWII.

‘Rejtő was sent to the then Soviet Union as a Jewish labour serviceman at the end of 1942, into occupied territory, and probably died in early 1943, about two weeks before the Soviet counterattack’—explains Olivér Perczel, the scholar who has so far been the most thorough researcher of the writer’s death.[ii] According to Rejtő’s casualty record, he was first listed as dead, but this was then changed to missing, and the location was listed as Yevdokovo (about 30 km southwest of the Don River). But the practice of the time was that anyone who was not seen falling was automatically deemed missing. The date doesn’t tell us much either: unknown disappearance/death dates were usually entered randomly in the records, and the date (1 January) given as the day of his death is also suspicious. Another Rejtő legend is related to this. Supposedly, his last words would have been ‘this year is starting well’, but this is probably a myth. According to a later pencil correction in his files, he was exhumed in 1944, but Perczel says this is probably wrong—no one was exhuming fallen Hungarian soldiers in that region at the time.

But Just How did Rejtő Die?

Israeli-Hungarian publisher Miklós Faragó wrote a full-page article about Rejtő in the Israeli Új Kelet (New East) magazine on 12 May 1961, according to which the writer ‘perished in the clutches of Hungarian soldiers in Ukraine’. However, it seems obvious that the writer got carried away here. We don’t know for certain whether Rejtő was killed by soldiers, or by Hungarians at all. Labour service—especially on the Eastern Front —was a cruel thing, where Jews were decimated by Hungarian soldiers, the Germans, the Soviets, frost, hunger and disease alike.

Another legend was born regarding the 1971 film The Immortal Legionnaire Called P. Howard (directed by Tamás Somló, whose father himself died as a labour serviceman). A review of the film was written by Oszkár Zsadányi, a Communist from Pécs and a survivor of labour service (and also a spy for the Communist state security), in the columns of the religious Jewish newspaper Új Élet. The article of 15 September 1971 was followed by another article in the 15 October issue, which was not signed, but it is clear from the introductory lines that Zsadányi was also its author.

According to Zsadányi, after the article appeared, he was contacted by ex-labour serviceman Sándor Peredi, who told him that he himself had been a member of the labour squadron that was the subject of the film and in which Jenő Rejtő had died. ‘The company number was 109/27. They had to go to Nagykáta in the autumn of 1942. They had already been there for a week when Jenő Rejtő, whom he had only known from cafés, arrived in Nagykáta in a yellow overcoat, slippers, and without any luggage, as if he were going on a weekend trip.’

Peredi watched the film, and informed Zsadányi that ‘in contrast to the good company commander and the soldiers portrayed in the film, the reality was somewhat different. Two figures, among others, prove this. At the time of the draft, the company numbered 204. On liberation, 28 survived. The company commander was a first lieutenant named Opolczer, who was the type of coward who cared nothing for his men and who completely ceded leadership to his deputy, who, in absentia, was sentenced by the People’s Court to several years in prison. He was sentenced in absentia because he had escaped to the West. Sergeant Bódi, the sergeant on duty, was a sadistic monster who beat people bloody for no reason, and he was also responsible for the death of the young organist Sándor Kuti. After his liberation, Sergeant Bódi was taken to the People’s Court, and, as a testament to his guilt, he hanged himself in his cell the day before the main trial for fear of being prosecuted.’ After watching the film, Sándor Peredi felt that he owed his 176 slain comrades a debt of gratitude that the film’s writer and director had forgotten.’

Anecdotes and Legends

The article thus gives two points of reference: the infamous Nagykáta enlistment centre, and the no. 109/27 labour service company and its respective trials in the People’s Court. The trial of Lieutenant Colonel Lipót Muray, the head of the Nagykáta centre, is disappointing for the researcher. Rejtő’s name does not appear in it, but the ‘appearance in summer clothes’ story was indeed told in connection with another famous Hungarian Jew: according to this, it was the Olympic athlete Attila Petschauer who showed up clothed in this way. Perhaps this motif was later somehow passed on to Rejtő. There were other trials in connection with Nagykáta, but we learn nothing about Rejtő from these either.

And although the files of ‘Sergeant Bódi’ could not be found, Lieutenant Ödön Opolczer, commander of the no. 109/37 labour company (the number was probably mistakenly given by Peredi), was indeed tried before the People’s Court. His trial ended in acquittal. The case, however, deals with events in Transcarpathia in the spring of 1944, and Opolczer became commander of the company after Rejtő’s death, so it is perhaps not surprising that Rejtő’s name did not appear in the trial. On top of that, the notification of the writer’s death to his family clearly states that Rejtő’s company number was 101/19. Witness Peredi was thus deceived by his memory, and Zsadányi’s article was just another contribution to the ever-evolving and expanding collection of Rejtő legends.

Did He Die of Typhus?

Later on, some authors, referring to certain witnesses named ‘János Rajna’ and ‘Sándor Balla’, wrote that Rejtő died of typhus. That is not unrealistic, but unfortunately, we do not know from these works without references who Rajna and Balla were, what proves their claim, or where their testimonies can be found.[iii]

In any case, the memorial erected in 2002 in the Hungarian military cemetery on the outskirts of Rudinko in Voronezh County bears the following inscription: ‘Jenő Reich labour serviceman’, but this is symbolic, as the names of all the deceased and missing are inscribed on the monument. Some recent works state as a fact that Rejtő was beaten to death by Hungarian soldiers on the Eastern Front, although it is not clear on what basis this conclusion was drawn.

Until credible, primary sources are found, we must unfortunately accept that, apart from the fact that Rejtő disappeared as a labour serviceman on the Eastern Front, we know nothing more about his death.

[i] Gergely Thuróczy (ed.), A megtalált tragédia. Rejtő Jenő emlékére, Budapest, Szépmíves, 2016. Foreword.

[ii] Olivér Perczel, ‘Leváltári nyomozás a Rejtő-ügyben’, in: A megtalált tragédia. pp. 292-306.

[iii] Quoted in ‘Levéltári nyomozás’.