After most of the Hungarian left was forced into emigration following the fall of the Communist Soviet Republic in 1919, almost all its factions soon fell under the spell of communism or started accepting money from the successor states of the Monarchy.

Count Mihály Károlyi, for instance, tried to reach out to Vladimir Lenin—and at one point even took it upon himself to try to arrange it with the Soviet dictator that Transcarpathia remain part of Czechoslovakia—while Oszkár Jászi accepted financial support from the Yugoslav government to publish his writing in exile.[i] Trade union leader, writer, and social democratic politician Manó Buchinger, to cite another example, received an offer to set up a pro-Yugoslav social democratic newspaper in Novi Sad (formerly Újvidék) in Vojvodina.[ii]

However, none of these attempts yielded any real ‘results’ for the émigrés, and it is most likely that the Czechoslovaks and Yugoslavs who supported them in their own national interest wanted any results other than to disrupt a united Hungarian nationalist action in the international arena.

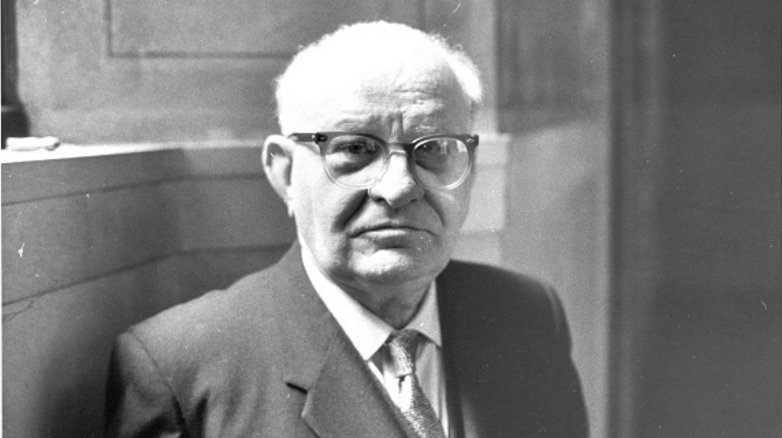

And although the greatest threat to the counter-revolutionary regime was the return of the Habsburg monarch Charles IV, there was indeed another politician lurking in the shadow of the Hungarian emigration who would have also been eager to seize power in Hungary. The communist dictator Béla Kun left little doubt in his articles about how he envisioned Hungary’s future. He named democracy and private property as his main enemies, but saw national and religious attachments as equally worthy of extermination: as he wrote, the ‘rotten crown’ of St Stephen would one day be crushed by the workers’ revolting hands.[iii] If some bourgeois sympathisers of communism accused Horthy of abolishing democracy, they too received a candid answer: Horthy was not abolishing democracy, he rather represented ‘real democracy’, because democracy is inherently dishonest and deceitful. The only solution, according to Kun, would have been to restore the dictatorship of the proletariat.[iv] He was not particularly bothered by the white terror: ‘To pity the suffering working class is the emotion of the bourgeois, the philanthropist. The revolutionary, hearing the cries of the old society’s mourning, is happy to hear the sounds of the revolution.’. He called the violence against his own former supporters ‘useful’, since the worsening of the situation of the workers could only mean an acceleration of the arrival of the communist revolution. ‘The worse, the better,’ his motto was.[v]

Given that at the time even social democrats and the working class grieved over Trianon, Kun’s following lines were particularly provocative: territorial losses ‘do not interest us in the least’, he said, since ‘we must take a direct and open stand’ against any revisionist aspirations. The acceptance of new post-war borders is, in his view, ‘the basis of the communist national policy in Central Europe.’.[vi] Kun even rejected the possibility of Hungarian cultural autonomy, saying that ‘if the oppressors have become oppressed in the successor states, this is today definitely not an important issue, as it will be solved in the blink of an eye by the social revolution.’[vii]

Compared to the writings of the Octobrists (pro-Károlyi leftists) and social-democratic émigrés, who were grumpy, bitter and preoccupied with their individual, private problems, Kun’s lines reveal the former dictator’s determination: ‘We are ready and waiting. It is doubtful how soon, but world imperialism, and with it white imperialism in Hungary, will fall. And then the Hungarian proletariat will welcome the communist dictatorship of the proletariat with open arms,’ he wrote in the spring of 1921.[viii] Although it was not the ‘open arms’ of the Hungarian proletariat that were awaiting him, but the Stalinist executioners, his ideology did indeed triumph a little less than a quarter of a century later.

Paradoxically, his views on democracy, political violence and capitalism were not much different from the ones who declared themselves to be opposed to Kun’s ‘revolution’ held, and in this respect there was more overlap between Kun and the contemporary nationalist racists than between Kun and the social-democratic or the left-leaning bourgeois emigration. In fact, the main achievements of the 1919 Soviet republic— the suppression of dissent, political terror and the complete abandonment of the institution of private property—were almost entirely embraced by the counter-revolutionary regime in its first two years, as demonstrated in particular by the events in the hazy months of the white terror.

[i] Tibor Hajdu, Károlyi Mihály, Budapest, Napvilág, 2012, 138, 146–147.

[ii] Politikatörténeti Intézet Levéltára (hereon cited as PIL), 696.f.124. 3.

[iii] PIL, 709.f.8. 3.

[iv] PIL, 709.f.8.

[v] György Borsányi, Kun Béla. Politikai életrajz, Budapest, Kossuth, 1979, 205.

[vi] PIL, 709.f.8.

[vii] PIL, 709.f.8.

[viii] PIL, 709.f.8.

Read Next