The following is an adapted version of an article written by Emese Hulej, originally published in Magyar Krónika.

Hungarian folk art combined with American modernity. Happy motherhood and artistic self-expression. The names of the Kárász girls are hardly known here in Hungary, while their works are preserved in the most important American museums to this day.

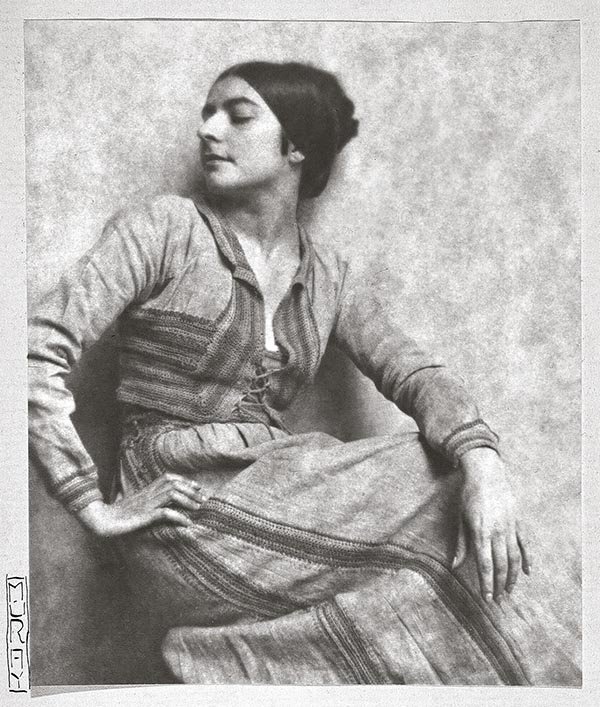

The Hungarian Heritage House’s exhibition titled Folk Fashion — Folklore in Fashion displays a picture of an elegant, folk art-embroidered women’s coat that was a big hit with women in turn-of-the-century New York. Its designer, Mariska Kárász, opened her salon on Madison Avenue in 1922, and who knows where her brand would have gone if her place full of fabrics, ready-made models, and designs hadn’t burned down. But alas, it did.

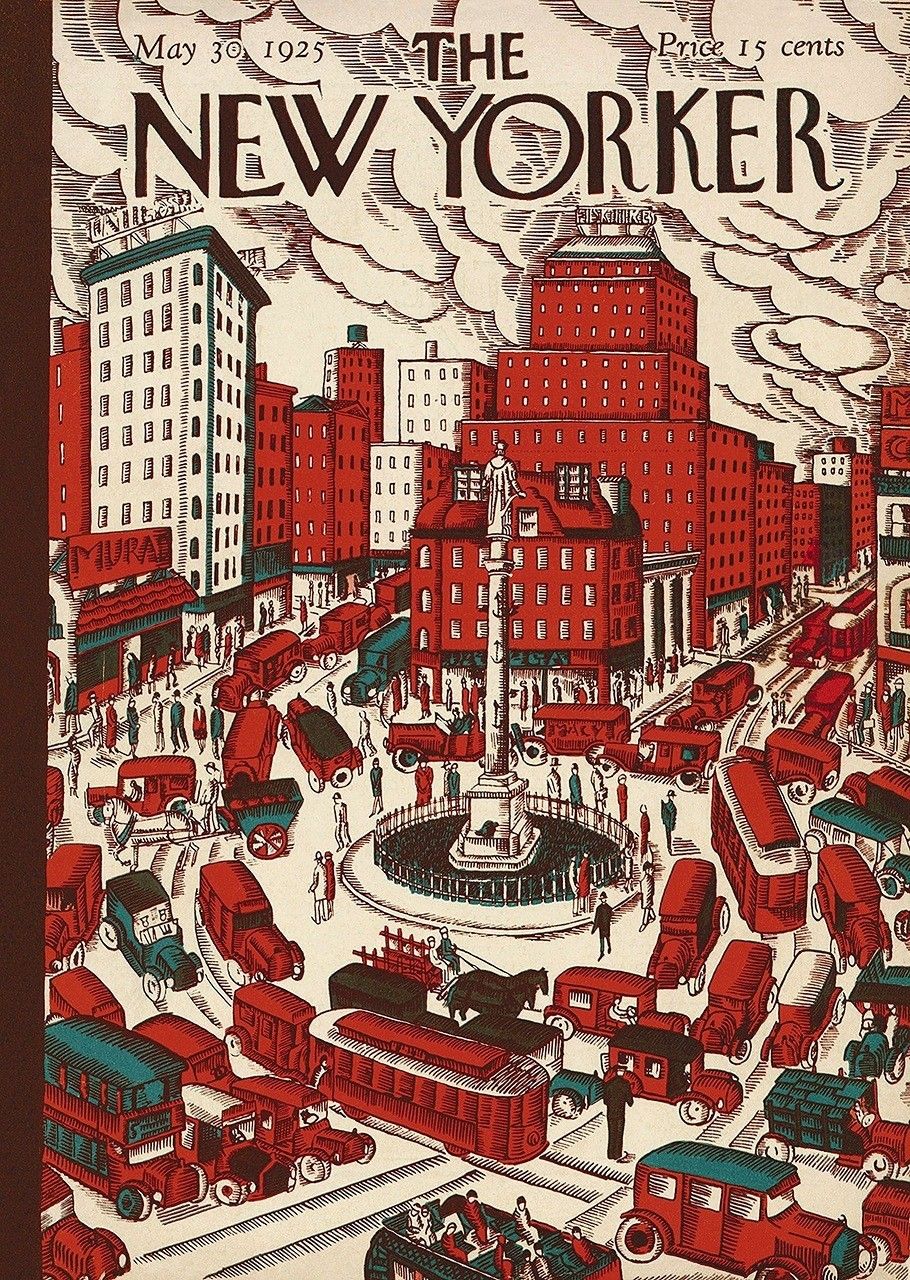

The names of the Kárász girls, Ilonka and Mariska, are little known here in Hungary, even though both were significant figures in American visual culture and are widely respected overseas. Ilonka drew two hundred covers for the legendary The New Yorker magazine and designed furniture, interiors, and fabrics, and her work, like that of her sister, is held in the most important American collections to this day.

Both girls were born in Hungary, and their father, who was most likely an underwear cleaner, died early of tuberculosis. His widow emigrated to America, followed by her children. Ilonka began studying at the textile department of the Hungarian Royal National School of Arts and Crafts in Budapest, where she acquired skills that won her the curiosity and appreciation of the Americans. She quickly entered the modern art scene, started a magazine, and began designing.

She married a Dutch chemist, and after their children were born, she turned to designing children’s rooms. Far ahead of her time, she designed furniture with rounded corners, a novelty at the time.

She and her husband built a twenty-one-room house for themselves outside the city, with elements reminiscent of Hungarian vernacular architecture and furniture—a carved wooden fence, an upstairs section resembling a church pulpit, a corner stove, and a corner bench. The house was natural, spacious, simple, and above all homey.

‘The names of the Kárász girls, Ilonka and Mariska, are little known here in Hungary, even though both were significant figures in American visual culture’

Her younger sister Mariska, born in 1898, was a skilled sewer and embroiderer already as a little girl and continued her studies in this line. When seeing her blouses, an American luxury department store ordered a collection from her, on which the young designer added Hungarian motifs. The next order, also from a large department store, was for pyjamas and nightdresses, decorated with Native American patterns. Typical of emigrants, she tried to combine the old and new worlds in her pieces, creating original and exciting clothing. American women loved her matyó and Buzsák embroidery and her folk art-embroidered coats, which, obviously, they had never seen before.

Always wearing trousers and a bob haircut, Mariska was a well-known and fashionable woman, and she had one great virtue: she was always capable of a fresh start. After the birth of her two daughters, she turned to children’s fashion, and even during her divorce and financial difficulties, she managed to make and paint tapestries, all of which were a huge success. She also wrote a book on needlework and sewing, which was way ahead of her time as well. She is the one who died earlier, aged only 62. Her sister Ilonka died in 1981.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.