Hungarian Conservative has launched a ten-part series of articles on the past decade and a half of the Hungarian economy and society, titled ‘Revealing the Facts’. Rather than looking at a lot of different, isolated data, it is worth providing an overview, comparing, and analysing trends over time, in order to understand the details. As we detailed in the previous parts, stable work and growing incomes), that is, the security of livelihood, are economically the most important for the Hungarian people. The improvement of living conditions, the reduction of poverty and the increase in family benefits has been the great achievements of recent years. Now inflation has not hit the Hungarian people as hard as it did during the regime change. Both the population and the economic players have been able to move forward, we have achieved substantial economic growth, which has been accompanied by a decade-long improvement in fertility. Today’s article, the eighth in the series, highlights the turnaround after 2010 in Hungary’s tax system.

Before 2010, Hungary’s tax system was inefficient. The tax authorities were only able to collect no more than one-fifth of the total VAT due. Taxes on labour were so high that they encouraged employers and employees alike not to declare all income, i.e. to employ illegally. The corporate tax rate also tended to discourage foreign investment, so when the state wanted to attract an investor to Hungary, it gave unique discounts that put Hungarian companies at a competitive disadvantage in the market. Business tax was also payable on total annual turnover, which meant that tax liabilities were incurred even if a company’s costs exceeded its revenues.

Government Vs. Tax Evasion

The tax policy of the previous government did not encourage companies to hire new workers, and in fact discouraged them from doing so. The cost of hiring a full-time employee for small and medium-sized enterprises – which employ three-quarters of Hungarian workers – was so high that companies could not afford it or found it unprofitable.

After the change of government in 2010, the tax system was fundamentally restructured. The basic principle was to reduce taxes on labour, while VAT became the main source of revenue and its collection was made much more efficient, significantly increasing budget revenues. Thanks to the right-wing turn, VAT evasion is no longer worthwhile in many respects; for example, the National Tax and Customs Administration maintains a publicly accessible database of businesses that have not fully complied with their tax obligations.

We have already achieved the most significant improvements in the efficiency of our tax system in Europe and among OECD countries. Let’s look at these key areas of taxation.

VAT Collection Is More Efficient, Unpaid VAT Has Decreased

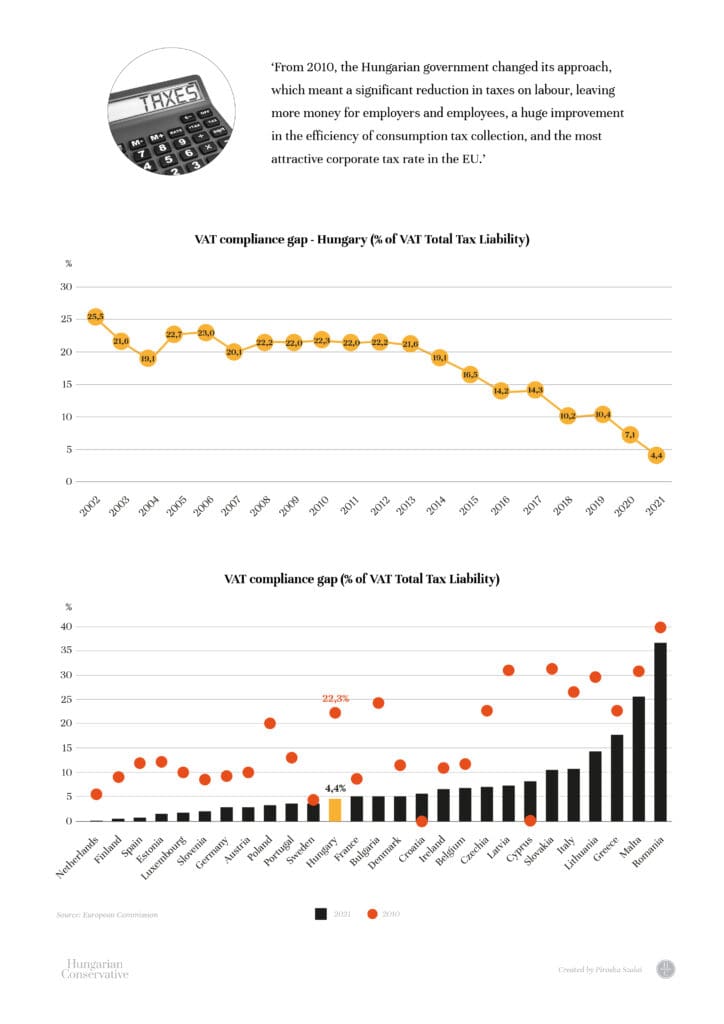

The VAT compliance gap is the VAT liability generated but not paid by economic agents. This ratio shows the efficiency of the tax administration and the tax system. According to the European Commission’s VAT Compliance Gap in the EU 2023 report, Hungary’s reduction in the VAT compliance gap since 2013 has been outstanding, making it one of the success stories among EU member states. Our improvement of 17.2 percentage points is the fourth largest after Poland, Slovakia, and Latvia. The improvement has not even stopped under Covid, with the latest figure for 2021 showing an uncollected VAT gap of only 4.4 per cent.

The improvement has been driven by a number of innovative tax measures. The tax office introduced online cash registers for retail, accommodation, and food services in 2014, the Electronic Public Road Trade Control System in 2015 and Real Time Invoice Reporting in 2018, which it has gradually expanded to cover the full range of businesses and the full volume of sales.

Labour Income Tax Deductions in Hungary See the Largest Drop Among OECD Countries

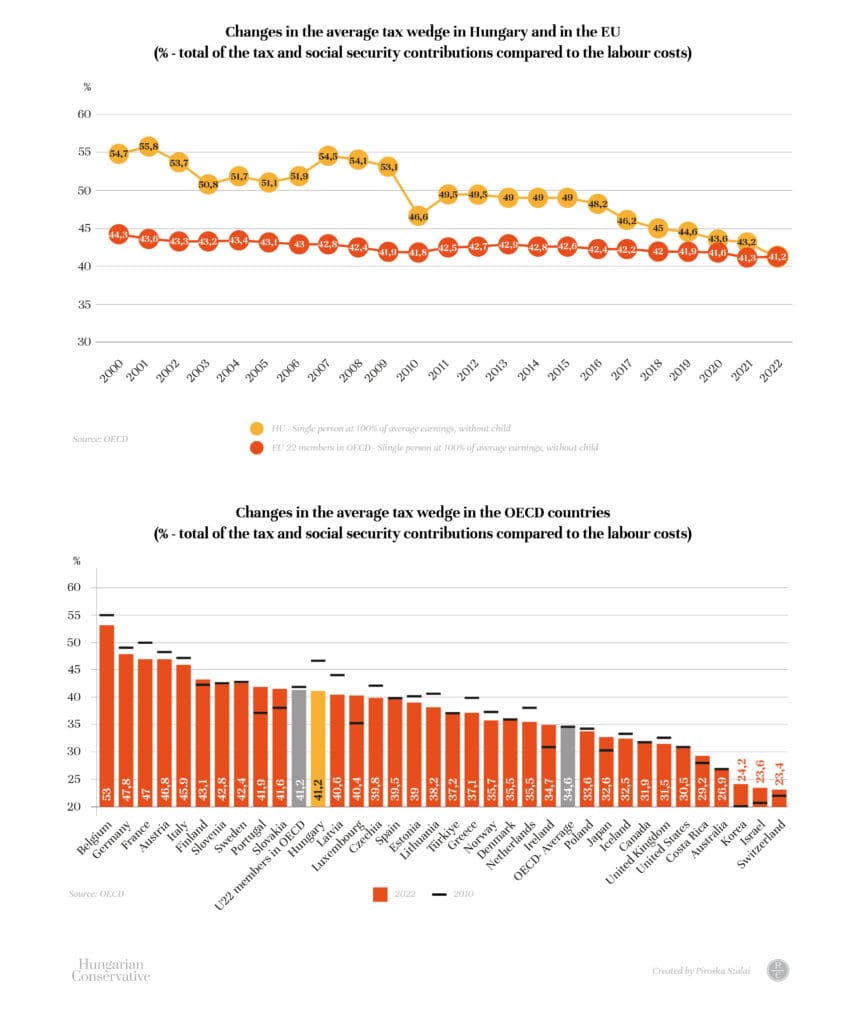

The average tax wedge shows the relationship between the total cost of wages paid by an employer to an ‘average worker’ and the net wages taken home by the worker. The tax wedge is the quotient of the total amount of taxes on labour (personal income tax, employee and employer contributions, social security contributions) and the total wage cost (net wages and taxes on labour).

Until 2009, Hungary had the second largest deduction after Belgium. It was a multi-rate personal income tax system, and the top of the band was so low that even average incomes fell within the band of the highest rate. As a result, even on average earnings, the state deducted more than half of the total wage bill, while the EU average was more than 10 percentage points lower. In fact, if the average worker’s earnings had risen, the state would’ve taken three quarters of the increase.

From 2011, the personal income tax system was changed to a single rate, so that no matter how much a worker’s income increased, the same proportion of the increase was deducted, significantly reducing undeclared work. The rate was first 16 per cent and then 15 per cent, the same as the previous lower rate. In 2010, only those with at least three children were eligible for a small tax credit, but from 2011 this was extended to those with one child. These changes meant tax cuts for the majority of employees. From 2013, employers’ social insurance contributions were reduced for the first time for a certain group of employees, and from 2017 for all employees.

Wage Agreement Between Employers and Employees

The first Orbán government also raised the minimum wage substantially between 1998 and 2002. This is important not only for workers’ incomes, but also for competitiveness and labour shortages.

In 2016, the government proposed to reduce the social contribution tax paid by employers each year between 2017-2022 if companies used the savings to increase wages. As a result, between 2017 and 2022, social contribution tax was cut by more than half. Meanwhile, despite the Covid-19 epidemic, wages have risen significantly – including in real terms – over the six-year period of the collective agreement.

The employer’s tax has been reduced from 28,5 per cent before 2013 to 13 per cent in 2022. Meanwhile, mothers with at least four children can work personal income tax-free for the rest of their lives, mothers under 30 and young people under 25 can earn tax-free up to the average income, and those who work while receiving a pension and their employers do not pay social security contributions. As a result of these measures, Hungary had the largest reduction in the average tax wedge of all OECD countries between 2010 and 2022, with a reduction of 5.5 percentage points for a single person earning 100 per cent of the average income without a child. The Hungarian tax wedge is already lower than the average of the 22 EU members in the OECD. In addition, the state’s income tax revenues have risen significantly as the labour market has become whiter—thus increasing the number of people employed —, incomes have risen very significantly, and poverty has fallen.

Single-digit Corporate Tax in Hungary

From 2017, Hungary has a single-digit corporate tax rate of 9 per cent, the lowest in the European Union, but companies also have to pay a business tax and innovation contributions.

The corporate tax rate was 19 per cent in 2010, which is the general rate in neighbouring countries such as Poland and the Czech Republic, but it is 8.5 per cent in Switzerland, for example. In Hungary, corporate income tax is paid to the state on a company’s profits. The government has tried to stimulate the economy and create more attractive conditions for investors by reducing corporate tax.

In the EU, however, only Hungary has a business tax (‘iparűzési adó’ in Hungarian), which is almost twice as burdensome for companies as the corporate tax. Business tax is based on income, so it is payable even if the company makes a loss in a given year. As the business tax is collected by local authorities and is the largest source of revenue in the cities and Budapest, there is a political risk in changing it, although it is important to modernise this tax, which has not changed significantly since it was introduced in 1988.

Tax innovations since 2010 have created a much simpler, less bureaucratic, and more automated system. For example, for almost 5 million taxpayers, the tax office prepares the digital draft income tax declaration, which only needs to be approved by the taxpayer. This is also much cheaper for the state, as there are no postal charges, for example. The tax office continues to modernise, and this year has seen innovations in the area of VAT digitalization.

From 2010 the Hungarian government changed the previous approach to taxation entirely. This meant a significant reduction in taxes on labour, leaving more money for employers and employees, a huge improvement in the efficiency of consumption tax collection, and the most attractive corporate tax rate in the EU. The government has no plans to increase tax rates but is developing innovations that will make tax compliance simpler, less administrative and more efficient for both the tax administration and the taxpayer. It is fair to say that Hungary’s tax innovation has now become a best practice for the EU.

Piroska Szalai is a labour market expert, a researcher at Economy and Competitiveness Research Institute of the Ludovika University of Public Service.

Kristóf Nagy and Mátyás Zsolt Varga are journalists at Mandiner.

Related articles: