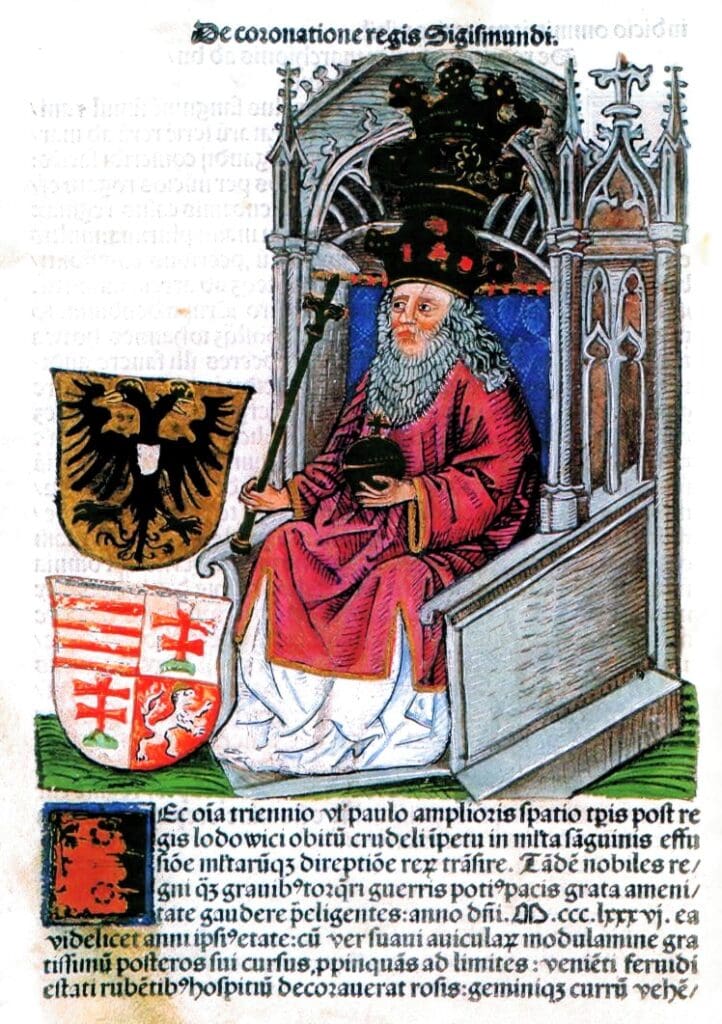

King Sigismund of Luxembourg (King 1387–1437, Emperor 1433–1437), son of Emperor Charles IV, not only won the hand of the daughter of King Louis the Great of Hungary and became King of Hungary in 1387 but also inherited the oppressive legacy of the Ottoman threat. The King tried to meet this challenge, but in 1396 his crusade was severely defeated at Nikopol (Nikápoly). However, he did not give up, capturing the most important Serbian fortress, Nándorfehérvár (Belgrade), in 1427 and setting out to attack Golubac (Galambóc).[1]

Galambóc in today’s Serbia, still an imposing fortress on the banks of the lower Danube section, first appears in the annals of history when Turkish invasions approached and even reached the former borders of Hungary. The castle was occupied by the Turks in 1390. As an important Danube crossing point and base for the Danube fleet, the castle was supposed to control and protect Hungary’s land and water routes from the south and support the anti-Turkish party in Serbia.[2]

Sigismund is not usually praised in military historical literature for the siege of Galambóc, although the King acted with great foresight and care.

In preparation for the siege, constructing the castle of Lászlóvára, (Coronini, formerly Koronini, Romania) on the opposite shore of Galambóc was a very forward-looking move. This is well illustrated by the fact that the castle was later incorporated into the Hungarian border castle system and entrusted to the Teutonic Knights.

Another important preparation of the Hungarians was the mobilization of the Danube fleet. Just imagine how imposing the Danube fleet of 22 ships, built in 1418 by Flemish masters, may have looked like, and at that time it could have already consisted of many more ships and was well fortified with cannons. The lion’s share of the siege was borne by the Hungarian ships gaining the upper hand on the Danube. The use of cannons by the Hungarians is also described in Turkish chronicles, recording their fearsome sound, demonstrating Sigismund’s interest in the military innovations of the time, such as firearms.[3]

Sigismund ordered the mobilization in the spring of 1428, and according to his itinerary, he already issued a charter from the camp below Galambóc on 27 April. However, there was a state of war on the Turkish front already since Sigismund’s military engagement in 1426. The King had been personally at the front since the end of 1426, first in Transylvania in 1427, then in Orsova (today’s Orșova in Romania) from August 1427, and in the Nándorfehérvár area from September 1427, when the Hungarians took possession of the city.

As in 1396, the troops, again an international coalition, were led by the new Temes (Timişian) Ban István Rozgonyi, and joined by a Polish relief force led by Czarny Zawisza (Zawisza the Black of Garbów), representing the Lithuanian Prince Vitold; the Romanians were represented by Dan the Voivode of Wallachia, and the new Serbian despot George Branković also sent his troops, led by Matko Talovac, hailing from Dubrovnik. The foreigners were joined by Venice’s enemies, including the Milanese envoy and Genoese crossbowmen. As to the size of the Hungarian army, modern literature traditionally gives an exaggerated estimate of 20,000 men, but it is certain that far fewer crossed the Danube to Galambóc on the opposite bank. Even if we assume that they crossed by bridge or boat, the siege did not require such a large army anyway, and as developments showed, they were not prepared for a battle in the field. Accordingly, the army would have been largely composed of infantrymen, who would have been of more use during the siege.

Even the preparations, so commendable as they were, proved to be insufficient for success. Perhaps the reason for the Hungarian defeat was that a month and a half (roughly from 27 April to 3 June 1418) proved too short to take the fortress, and as so often, with the arrival of the Ottoman relief army, the besiegers were caught between two fires.

The Ottoman army trapped the Hungarians on the banks of the Danube, from which the army, composed mostly of infantrymen, had no chance of breaking out.

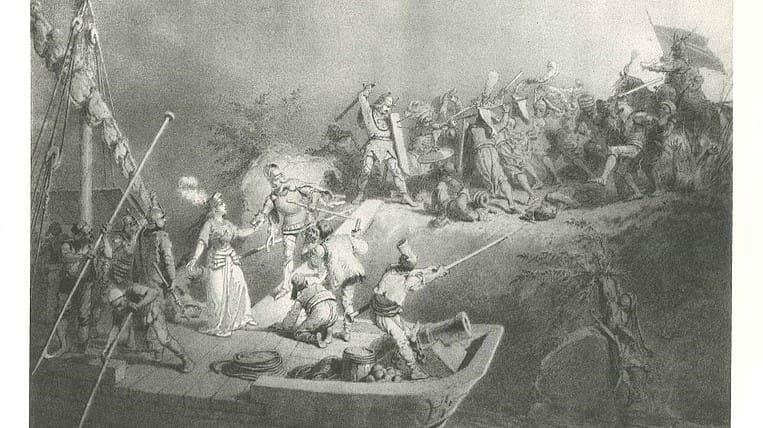

The Hungarian retreat and the crossing of the Danube started and went well for a while after a truce (which later became a truce of several years) with the leader of the Turks, beyler-bey of Rumelia Sinan, who had arrived on relief. The Turks, however, waited until only a few hundred Hungarians remained in their camp along the Danube, and then, in violation of the ceasefire, attempted to capture the Hungarian King. At that night panic must have broken out, and the fleeing Christian soldiers stormed the ships, almost leaving no room for the monarch himself. This episode is also well known from royal charters, where even the King praised the sacrifice of his followers.

The crossing of the Hungarian army was covered by foreign auxiliaries, such as the Wallachians and Poles, which the reports of casualties seem to confirm. All the cannons and the horses that were put ashore became Turkish loot, as mentioned by Turkish historians, too. The Polish Zawisza, already mentioned, defended the retreating troops to the bitter end and even disobeyed Sigismund, who ordered him to flee. These are said to have been his last words: ‘There is no boat big enough to lift my honour’. He was captured alive by the Turks, who later executed him. King Sigismund must have been sincerely grateful to the knight for his self-sacrificing fight, for which he made a donation to his widow and described his feat in his charter.

The international political background and consequences of the siege are no less interesting. The other stage of the Turkish front in Europe in 1428 was further south, with the Venetian–Turkish war for Thessaloniki and the Venetian territories of Albania. In Rome in 1429, Venetian and Hungarian politicians not without reason accused each other of failing to take joint action, for in 1430, after a few weeks of siege, Turkish troops marching with a Serbian auxiliary took Thessaloniki. Indeed, there remained hopelessly little room for manoeuvre and almost no opportunity to forge a Hungarian–Venetian alliance alongside the traditional Genoese–Hungarian alliance for Sigismund. By this time, the King could already be thinking of his forthcoming trip to Italy, which is obviously why he insisted on maintaining the Hungarian–Turkish truce and ratifying it the following year. Achieving a ceasefire was certainly one of Sigismund’s war aims, even if he wanted to enforce it by regaining Galambóc. Finally, Sigismund left the southern frontier in peace when, at the end of June 1430, he left Hungary for several years and set off for Italy to seek the imperial crown.

The seemingly insignificant Danube fortress has written its name in world history. Even the famous Burgundian traveller Bertrandon de la Broquière and the Hungarian poet Sebestyén Tinódi Lantos commemorated the siege in their travelogues in the 1500s. Thanks to the fame of the Polish knight who had died there, all Polish chroniclers, including Jan Dlugosz, recorded the event and his bravery have become a living legend to this day. Besides,

Sigismund also showed his true virtues as a monarch when he was not the first to flee,

proving that he was indeed worthy of the blessed sword bestowed by the Popes on heroes of Christianity in 1414. The King waited in the camp on the Danube bank on the Galambóc side of the river for his army to cross, offering them a personal guarantee. In today’s Hungary, the event is also remembered from famous Hungarian poet János Arany’s ballad (1852), commemorating the heroic wife of the Ban of Temes, who handled the cannons and saved the King with her own hands. According to Arany’s poem, ‘There’s not a word speaking of Sigismund’s triumph; All the wide world speaks of Cecilia Rozgonyi’.

Indeed, the least of the glory went to Sigismund, the King himself.

[1] László Veszprémy, ‘King Sigismund of Luxemburg at Golubac (Galamboc)’, in Christian Gastgeber, Ioan-Aurel Pop, Oliver Jens Schmitt, and Alexandru Pop (eds.), Worlds in Change: Church Union and Crusading in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries, Transylvanian Review, Vol. 18, No. 2, 2009, pp. 291–308.

[2] Pál Engel, The Realm of St Stephen. A History of Medieval Hungary 895–1526, London, 2001, pp. 231–238.

[3] László Veszprémy, ‘Militärtechnische Innovationen und Handschriften aus dem Umfeld Sigismunds’, in Imre Takács (ed.), Sigismundus Rex et Imperator. Kunst und Kultur zur Zeit Sigismunds von Luxemburg 1387-1437, Mainz, 2006, pp. 287–291.

Related articles: