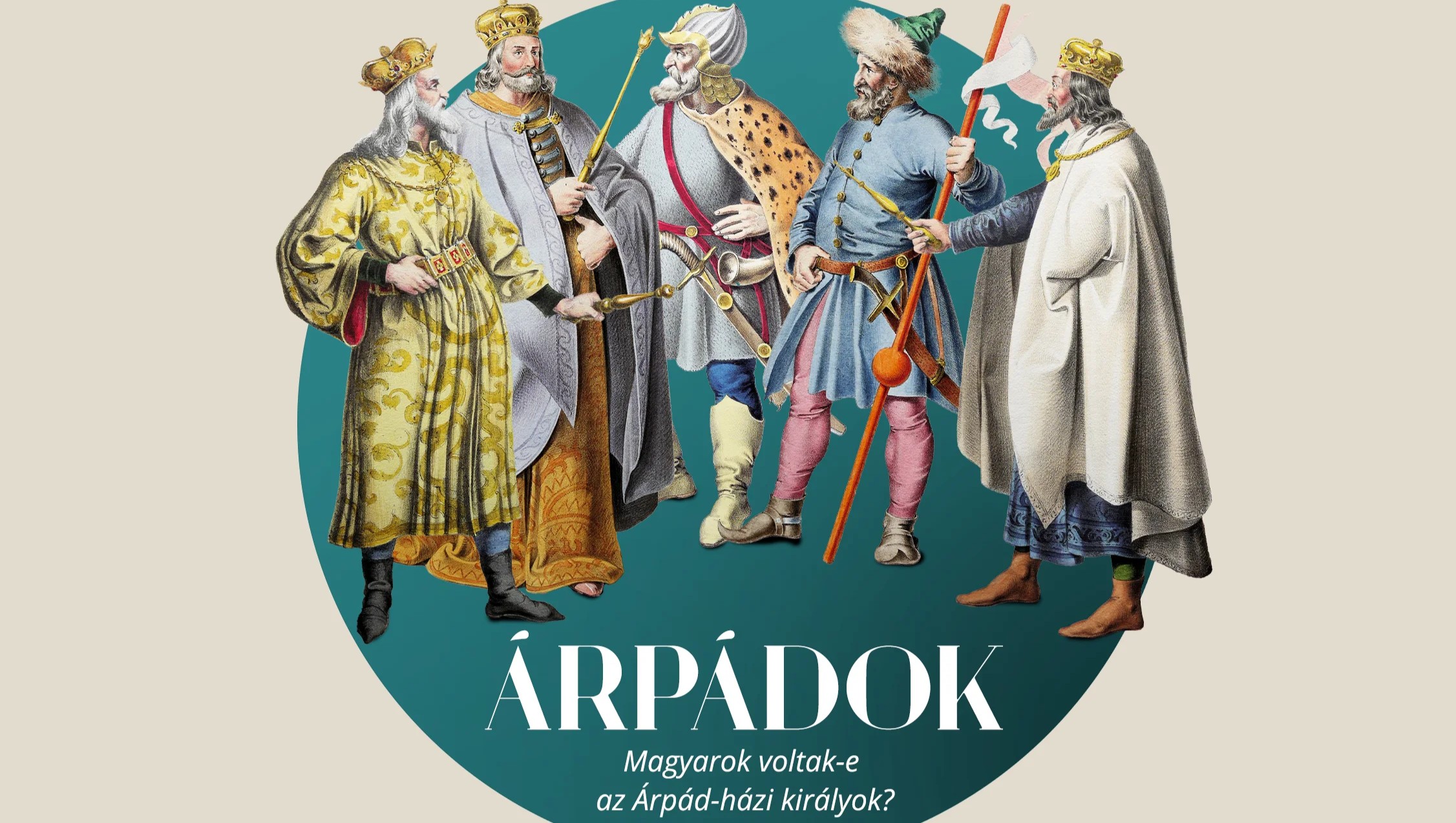

The following is an adapted version of an article written by Gábor Bencsik, originally published in Magyar Krónika.

For more than four and a half centuries, Hungary was ruled by members of the first Hungarian royal house. In its series about the Árpád Dynasty, Magyar Krónika recalls the history of our princes and kings from the 830s to 1301, until the extinction of the House.

‘Before this Árpád, the Turks [Hungarians] had no other prince, and from this time onwards, from this clan will be the prince of Turkia.’

– Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus, On Administering the Empire

The new series of Magyar Krónika takes a look at the members of the first Hungarian dynasty, with the addition of two leaders of the Hungarian state who had no family connection with the Árpáds, but without whom the story would be incomplete. This includes the first known grand prince, Levedi, about whom we know very little, but who we may rightly suspect was the organizer of the wandering Hungarian tribal alliance, and thus one of the founders of the nomadic Hungarian state, as well as our third king, Samuel Aba, who was certainly not descended from Árpád’s family, or even from his clan, but who ruled Hungary as its legitimate king. Besides, our second king, Peter, was not a male descendant either, but we regard him as a dynasty member through his mother. The others, seven princes and 23 kings, are all direct descendants.

It goes without saying that the House of Árpád is the first Hungarian dynasty of rulers. But is this statement really so self-evident? As far as the ruler is concerned, there can be no doubt—the first monarch clearly stands its ground if we add the word ‘known’, since we cannot rule out the possibility that princes by descent existed already before Levedi. The Árpád and Hungarian attributes, however, deserve some deeper reflection.

Árpád Dynasty?

We say Árpád Dynasty, or the House of Árpád, the name given by historical tradition to the first ruling dynasty of the Hungarian state. The fact that this is well-founded is also confirmed by the description of the Hungarians written by Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus around 950 and by his above-quoted passage. We must add, however, that neither the rulers themselves nor their contemporaries called themselves by this name, although they were aware of Árpád as a founding ancestor. The term ‘House of Árpád’ first appeared only in the 18th century, and its widespread use is probably due to the most influential historian of the time, István Katona, a Jesuit.

We can find a reference to how they called themselves in the chronicle of Simon of Kéza, written in the 1280s, during the reign of King Ladislaus IV. Simon of Kéza mentions the Turul clan (de genere Turul) twice, in one place specifically in connection with the descent of Árpád, and the King’s entourage, for whom the work was written, obviously had no objection to this. Nevertheless, several documents suggest that the rulers preferred to call themselves the Clan of the Holy Kings. In 1083 Saint Ladislaus himself initiated the canonization of Stephen I, Emeric, Gerard, and the two hermits of Zobor, thereby elevating his dynasty to the rank of European royal houses of saints. Ladislaus himself was canonized in 1192, further strengthening the idea of a lineage of holy kings.

Hungarian?

Although it was taken for granted in the Middle Ages, it is still surprising that all the kings of the Hungarian Árpád Dynasty from Solomon onwards had foreign princesses as mothers. Of the royal princesses who came to Hungary through dynastic marriage, two were Polish, four were from Kyiv, one was from Limburg (Belgium), two were Italian, three were Serbian, three were Byzantine, one was Spanish, one was German, and one was Cuman. In addition, due to various complications, mainly struggles for the throne, several of our monarchs were brought up abroad before coming to the throne at home. These two factors sometimes raise the question of how far our kings can be considered really Hungarian.

‘Multilingualism was most certainly present in the royal court, yet there is no reason to suppose that Hungarian was not the common language’

If a time traveller were to ask one of our Árpád kings if he considered himself Hungarian, growing up in a foreign language environment with a foreign mother, he would probably not understand the question. He might even ask back what else he could consider himself. Our present-day concept of ethnicity would be completely alien to him—he would obviously consider himself Hungarian, the head of the Hungarian state. And we can certainly consider him as such, too.

However, it is more difficult to give a well-founded answer to the question of what language our kings spoke. 99 per cent of the literacy of the time was in Latin, but this does not tell us anything about the everyday use of the language because documents were written in Latin elsewhere, too. We do know, however, that Hungarian kings were accompanied by many foreigners, as were other kings. We have already mentioned the royal wives, the Hont-Pázmány (Hunt-Poznan) knights, and Bishop Gerard, but there were also strange cases, such as the English princes who returned from exile in Kyiv to join King Andrew I, who had taken the throne. Multilingualism was most certainly present in the royal court, yet there is no reason to suppose that Hungarian was not the common language—as was Polish in the Polish court, German in the German, Serbian in the Serbian, and so on.

In addition to ethnic self-identification and the language spoken, there is another argument in favour of the Hungarian status of the Árpád monarchs, which is even stronger than the other two from our point of view: they were first the rulers of the nomadic Hungarian state and then of the Hungarian Kingdom, and if they acquired other crowns, they did so by right.

Here is a complete list of the Hungarian princes and rulers until 1301, including the unrecognized counter-kings:

• Levedi (not of the Árpád Dynasty)

• Álmos

• Árpád

• Zolta

• Fajsz

• Taksony

• Géza

• (Saint) Stephen I

• (Orseolo) Peter

• Samuel Aba (not of the Árpád Dynasty)

• Andrew I

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.