The most significant challenge to family life today comes not from school or peer groups, but from new media. Media consumption figures have shown a significant increase over the last few decades. Not only has media colonized leisure time, but it has taken over a large share of working time and family time as well. The influencers that strike a chord with young people have moved into our homes, they sit with us at the Sunday dinner table and accompany us almost everywhere. What do influencers offer? Why do teenagers and young adults follow them, cling to them; why do they choose them as role models? Or do they? What is the extent of their connection with them? Data from recent representative research conducted by the Youth Research Institute explored some of these questions, with a particular focus on political opinion formation.

Many in Hungary remember the story of Zente, a young boy with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA1) from five years ago, who raised funds for his life-saving medical treatment through public donations, but few will recall that the necessary 700m HUF was raised in record time, thanks in large part to the support of influencers, YouTubers and internet celebrities. Zente’s story has taught us that there is a huge potential in Hungary for influencers to support civic causes (as well).

Recently, there has been considerable media attention on influencers’ comments on public issues, particularly their role in shaping political opinion. For the 16 February 2024 rally demanding more government efforts to protect children, influencers were able to bring hundreds of thousands of people onto the streets of Budapest, which the political community opposing the government had previously failed to do despite many attempts. The event, unprecedented both in media history and the public sphere, is a testament to influencers’ ability to stimulate activity, and has led many to ask whether they can shape the political views of young people who are avid consumers of their content, and if they are able to convert online engagement into action in the form of votes.

Influencers Can Engage Young People, and It’s OK if They Earn Money, Too

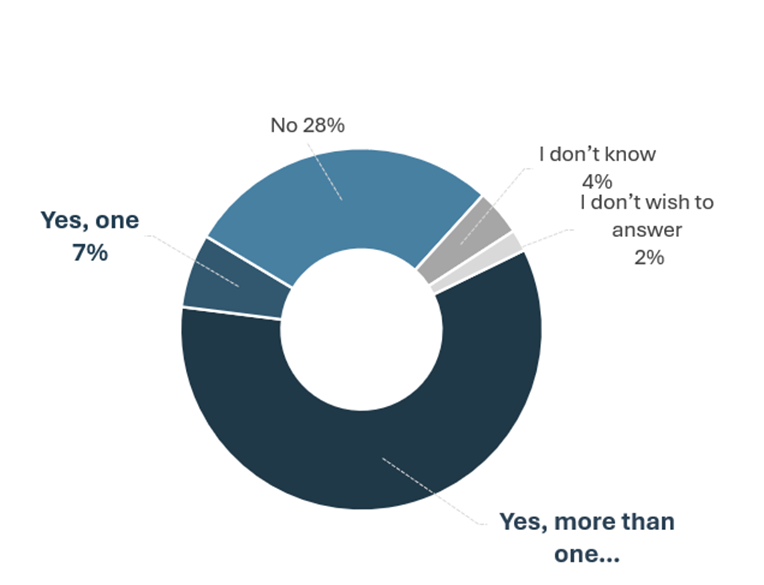

A representative survey looking specifically at influencer-generated content was conducted among Hungarian youth aged 15–29 in early 2024. The survey of 1,000 respondents found that most young people do follow influencers/YouTubers: most of them follow more than one (59 per cent), but two-thirds (66 per cent) follow at least one. There is a difference among genders, with a higher proportion of females following influencers, typically more than one. The most engaged age group is that of 18–24-year-olds, where nearly three-quarters (71 per cent) follow influencers.

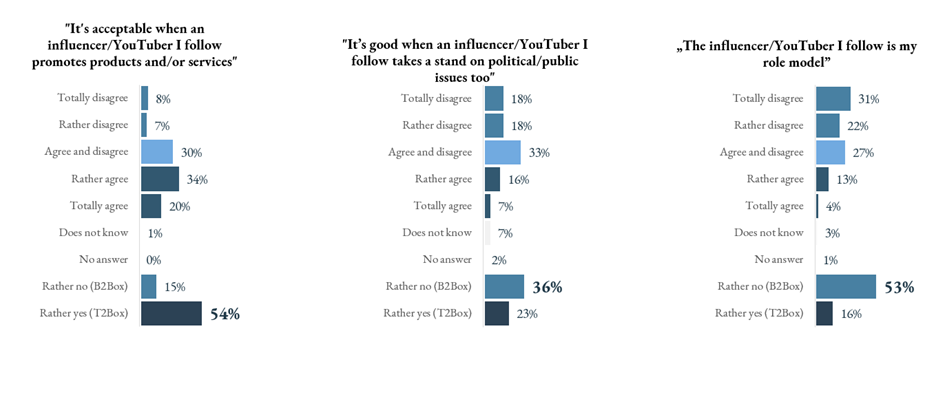

It happens less often that influencers selflessly support a cause, as they more often produce sponsored content that is generally tolerated by their audience. Research results from the Youth Research Institute suggest that while the impact of influencers is not negligible, the majority of young people continue to seek out such content for entertainment purposes. Previous research has also shown that followers approve of content creators generating advertising revenue through their activities. More than half of 15–29-year-olds (54 per cent) surveyed consider it more or less acceptable for an influencer/YouTuber they follow to advertise products and services.

Influencers Should Stay Out of Politics

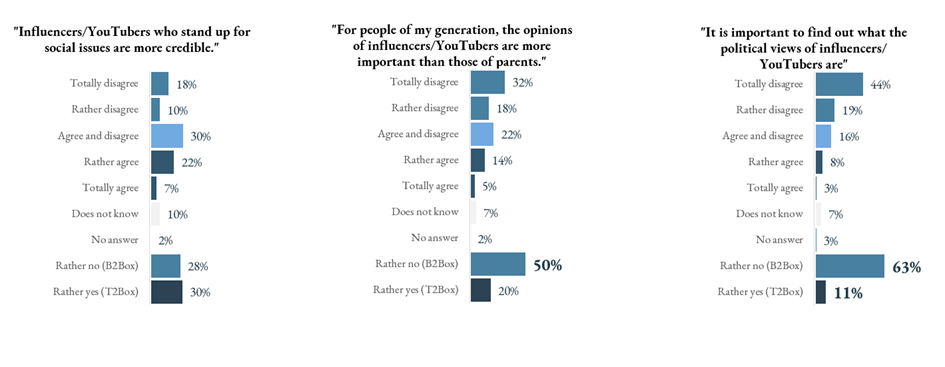

One might think that standing up for civic causes does not produce a financial return while it does increase credibility, but the matter is not that clearcut. Almost a third (30 per cent) of 15–29-year-olds surveyed believe that influencers who support civic causes are more credible, but almost the same proportion (28 per cent) disagree with this statement. Young people are thus divided on the opinion-shaping behaviour of influencers on social issues, with a higher proportion of those who follow more than one content creators believing that such influencers are more credible (38 per cent) than those who do not consume influencer content (17 per cent). The gender divide is also significant, with over a third of females (35 per cent) and a quarter of males (25 per cent) believing that content creators who take a stand on social issues are more credible.

For young people, however, social issues and politics do not mean the same thing. Previous research has shown that a good number of those open to social issues regard politics as something different from the dictionary definition of the word. For them politics is more about party political mudwrestling than discussing societal problems, therefore, politics is the business of politicians, and influencers should not get themselves involved. It is a remarkable finding that there are more followers who believe that it is not right for the content creator they follow to take a stand on political issues (36 vs. 23 per cent), and it seems that there is no difference of opinion between the different social groups, and socio-economic characteristics show no difference in the matter, either.

Extending the question beyond followers, we can observe that nearly two-thirds of young Hungarians aged 15-29 (63 per cent) do not consider it important to find out what political views an influencer represents. Those who follow several content creators typically feel this to be less important (10 per cent) than those who only follow one influencer (25 per cent), but even among them there are almost twice as many who do not consider it important to be aware of an influencer’s political views.

It is important to note that the Youth Research Institute’s survey was completed before the pardon scandal that triggered the demonstration in Budapest on February 16, 2024, therefore this specific case could not have influenced the respondents.

The Product May Contain Traces of Role Models

Through conveying certain values and norms, influencer-generated content may incorporate ideological elements even in the absence of direct political messages. The very act of communicating, even language use, may serve as a model for young people. International research shows that the values and norms conveyed by content creators do not always match those of the family or school in the traditional spaces of socialisation. Do influencers’ words carry more weight than those of the parents? Could YouTubers become role models?

A fifth of 15–29-year-olds (20 per cent) surveyed said that the opinions of influencers or YouTubers are more important to young people than those of their parents. Half of all respondents (50 per cent) disagree with this statement, forming the majority opinion. Looking at the question by age group, the proportion of respondents in agreement with the statement decreases as the ages increase: 25 percent of 15–17-year-olds, 20 per cent of 18–24-year-olds, and 14 per cent of 25–29-year-olds agree that influencers’ opinions carry more importance than those of parents.

Influencers are not perceived as role models by the majority of young people (53 per cent), with only 16 per cent saying that they agree or strongly agree with the statement that the influencer they follow (also) acts as a role model for them. Influencers can be perceived as role models by boys and girls in equal proportion, but with significant differences in age. Typically, younger people are more likely to think of the influencer they follow as a role model, with one-fifth (22 per cent) of 15–17-year-olds, 17 per cent of 18–24-year-olds and 13 per cent of 25–29-year-olds considering an influencer they follow as a role model.

Overall, 7 per cent of 15–29-year-olds in Hungary say that the opinions of influencers carry more weight for their generation than those of their parents, and that they consider a content creator they follow a role model, which also reinforces the importance of personal relationships and especially family, among young people.

Related articles: