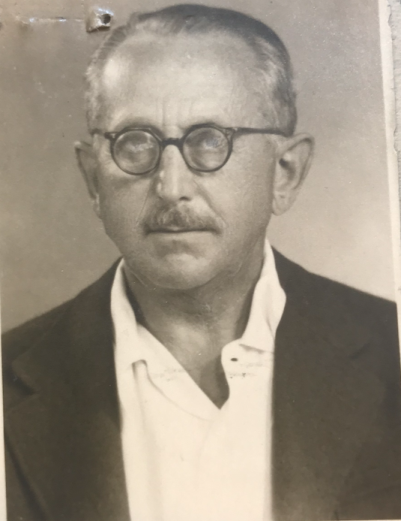

Although he was an important figure in the Hungarian-language Zionist movement in Yugoslavia, and one of the few Hungarian Jewish members of the right-wing Zionist movement—Revisionism—to reach a high position, not a single article has been written about the life of Gyula Dohány yet.

Dohány was born on 23 March 1884 in Nagybecskerek, Torontál County, into a highly assimilated Jewish family. He had two older siblings and several younger ones, and his family’s financial situation was likely difficult, as he wrote to the bar association as a young lawyer that he and his brothers were supporting their family.[1]

He studied law in Budapest, became a legal trainee in the capital in 1905, and, after passing his bar exam, began practicing in Károlyfalva, Temes County, in 1910. During World War I, he served at the military prosecutor’s office in Temesvár and was discharged with the rank of ‘first lieutenant-judge’. It was at the prosecutor’s office that he met another now-forgotten figure of Hungarian Zionism, Baruch Tomaschoff, who one evening dragged him to a lecture by Alexander Marmorek, a Galicia-born French biologist and Zionist orator, who was visiting the city. Dohány formed a lifelong friendship with Marmorek, and the speaker won over the previously highly assimilationist Dohány to the Zionist cause forever.

As a Zionist, he first appeared at the ‘preparatory committee meeting’ of the Hungarian Zionist Association’s national conference in May 1918. However, he truly stepped into the spotlight after 1 November 1918, when, at the request of the Aster Revolution government’s commissioner Ottó Róth, he and Tomaschoff founded the Jewish National Committee in Temesvár. Several similar committees soon followed across the country, and while a committee had already been formed earlier in Transcarpathia under the leadership of Illés Blank, the move nevertheless propelled Dohány’s name into the national press.[2] They printed and distributed 2,000 copies of Marmorek’s speeches—an astonishing achievement at the time—, which drew the ire of the local assimilated, neológ Jewish community.

Zionist newspapers reported that at the end of December 1918, Dohány held talks with Oszkár Jászi, the new government’s minister of nationalities. The papers claimed that this meeting led Jászi to issue his famous statement—widely celebrated in Zionist circles—recognizing the revolutionary government’s support for Jewish national aspirations. However, in reality, this declaration had been issued several days before the alleged meeting.

Nevertheless, Dohány reportedly submitted a Zionist memorandum to the government, the full text of which is only partially known. According to a January 1919 article in the Jewish paper Múlt és Jövő (Past and Future), the memorandum primarily protested against antisemitic riots in areas populated by national minorities and argued that the government would need the support of the Jewish community, organized as a nationality, during the upcoming peace negotiations.

In 1919 (according to the text, six weeks after the revolution, though the manuscript actually dates it to the final days of 1918), Dohány published a booklet in Temesvár titled The National Movement of the Jews.

The pamphlet began by noting that while there had recently been debates about whether a ‘Jewish Question’ existed in Hungary, now Jews in the provinces lived in fear. Dohány argued that there was no point in tiptoeing around the issue—Hungarians were mature citizens, and therefore, the matter had to be discussed openly, without waiting for the approval of the ‘paternalistic state’.

In tone, the pamphlet was optimistic in the sense that it framed Jewish survival as a historical certainty, noting that Jews had outlived even the fall of the Roman Empire and that history was now merely repeating itself. Interestingly, however, he then began praising the values of radicalism (socialism)—undoubtedly a reflection of the revolutionary climate of the time. He contended that Hungarian Jews had been a steadfast pillar of the capitalist Monarchy, but had they embraced radicalism earlier, they would not be in their current predicament.

‘The pamphlet was optimistic in the sense that it framed Jewish survival as a historical certainty’

Jews, he noted, had been at the forefront of radicalism, yet after four years of senseless bloodshed, they were now viewed as exploiters and capitalists. Assimilation, he argued, was not a viable path, particularly in national minority regions: for the ‘tóts’ (Slovaks), Jews were Hungarians, while for Hungarians, they were not Hungarian enough. Therefore, Dohány advocated for radicalism while seeking to establish Jewish cultural life within it. His position was thus quite close to that of the Bund,[3] especially since he clarified that, in his view, Zionism did not advocate emigration—those born in Hungary could live out their entire lives there. Finally, he outlined several key demands: a certain degree of Jewish separation (a ‘register’), national self-definition, democratic Jewish elections, the separation of national Jewish life from religious communities, and state support for the entire programme.[4]

From a modern perspective, the pamphlet is striking because one of the first actions of the 1919 communist regime that soon replaced the Aster Government was to ban Zionism. Later Dohány would align himself with the most anti-Marxist faction of Zionism, Revisionism. Yet the text clearly reflects the revolutionary fervour of its time, with its author adapting his message to align with the prevailing political climate.

Temesvár soon became a part of Romania, and Dohány relocated to Novi Sad (Újvidék), part of the nascent Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Zionism was experiencing a surge in the newly formed Yugoslavia at the time. However, it received less support than in Czechoslovakia or Romania, and Jews were not recognized as a national minority. The establishment of Zionist newspapers and organizations provoked the disapproval of assimilated Jews. In an article published on 10 January 1922, Jakov Fischer, a community leader in Subotica (Szabadka), argued that Jews, having received a Hungarian education and grown up to be Hungarian patriots, should align themselves with Hungarian political organizations. Dohány rejected this view in his response, stating that it would put them at odds with their fellow Jews who followed a different, state-favoured ideology—Zionism. Historian Zoltán Dévavári summarizes the debate as follows: ‘Dohány argued that in such a tense and already polarized situation, Jews would be attacked by the authorities and the Slavic majority not only for being Jewish but specifically for being Hungarian Jews. Therefore, their best option was independent political action based on Zionism.’[5]

Despite Zionist hopes, numerous antisemitic atrocities occurred in Yugoslavia at this time. ‘We, the Jews of Vojvodina, endure the insults that repeatedly appear in the local press helplessly and in silence. Weak and disorganized, we silently tolerate official persecution and the mass expulsion of Jewish families from their homes,’ Dohány lamented in an article in the Jüdisches Volksblatt in 1922.[6]

A year later Dohány wrote about German racial theory in the Zionist journal Haivri, published in Novi Sad. With astonishing foresight, he predicted that German racial ideology would dominate all other European nationalisms and that the ‘Jew-murdering National Socialists’ planned to ghettoize Jews before ‘neutralizing all who live there’. This article was notably more conservative than his 1919 pamphlet. He argued that German racial theory had risen to prominence in a Europe stripped of its moral foundations. ‘The great cultural community of nations, human and national rights, equality, fraternity, freedom, world peace—these have all become empty illusions,’ he opined.

‘The great cultural community of nations, human and national rights, equality, fraternity, freedom, world peace—these have all become empty illusions’

Since these ideals had failed, he claimed: ‘all that remains is the granite foundation of Moses’ laws and ethical principles.’ Socialism was not a solution because ‘it is retreating step by step, Bolshevism is a failure’. Only ‘Moses’ categorical imperative—“six days you shall work, and on the seventh you shall rest”—can alleviate the suffering of the workers.’ Liberalism, socialism, and patriotic assimilation had all collapsed in the face of antisemitism, which was stronger than ever. According to Dohány, the only solution was to embrace Jewish identity, as ‘all other prescriptions have failed.’[7]

It is not entirely clear when he first came into contact with the Revisionists. Betar, the Revisionist youth organization was founded by Ze’ev (Vladimir) Jabotinsky in 1923, and Hatzohar (Brit HaTzionim HaRevisionistim, Union of Revisionist Zionists) in 1925. These groups were fuelled by the Zionist failure to realize the promises of the Balfour declaration. By 1927, Dohány was already writing about how colonization in Palestine had slowed down, land prices were approaching those of major Western cities due to Arab price gouging, and the British were not keeping their promises, therefore a ‘second’ Balfour Declaration was needed. Betar was established in Novi Sad in 1933, with Viktor Stark as its first leader. At the same time, according to the press, Dohány became the president of the Jewish National Union (Revisionists). Betar also had local publications, including Tagar and Ever Ha’Yarden, while the Revisionists’ main newspaper was Malchut Yisrael.[8]

In December 1933 Jabotinsky greeted the new newspaper in a French letter: ‘I greet our new-born sibling, the Union of Revisionist Zionists of Yugoslavia, its leaders, members, and my journalist colleagues who have taken on the task of editing the Malchut Yisrael journal. Their struggle begins at the most defining moment in Jewish history since the creation of the diaspora. Even in the lifetime of those who are young today, our national future will be decided: a Jewish state on both sides of the Jordan, or the torment of complete destruction.’[9]

In 1935 Jabotinsky’s revisionists split from the World Zionist Organization and founded the New Zionist Organization (NZO). Dohány faithfully followed his leader, and in February 1936, the New Zionist Organization of Yugoslavia was founded in 25 settlements, with Dohány as its president. From the list of the leadership, it is clear that a significant number of Hungarian Jews were behind the organization of this group as well.[10]

In 1936 Dohány published another pamphlet, this time in German, titled The Truth about Palestine and the Jewish National Home. The main topic of the pamphlet was the Palestinian disturbances (especially the April 1936 Jaffa pogrom). Interestingly, Dohány’s main argument was that the whole issue was unimportant and that the press was paying too much attention to it. This argument was not entirely uncommon among Zionists, who tried to view the 1936–1939 Palestinian Arab uprising—which claimed thousands of victims, including about 500 Jews—as something trivial. The pamphlet then focused primarily on criticizing the British mandate authorities, condemning them for not supporting his proposed solution and for not allowing Jabotinsky into the country.[11]

By this time, Dohány’s relationship with Jabotinsky had become friendly, which was not self-evident, as the revisionist movement was riddled with internal conflicts. In 1939 Dohány certainly invited Jabotinsky to Yugoslavia, even though the Jewish leader had already visited Novi Sad, Zagreb, and Senta (Zenta) in 1935.[12] The leader of revisionism continued to correspond with Dohány until the end of his life. On 29 May 1940, for example, he wrote from New York: ‘Now, however, we are probably facing even greater catastrophes. It is possible that everything my generation has lived for and fought for in Jewish and general terms is now being destroyed. Who knows if we will ever meet again, what the world will be like when we meet, and what we ourselves will be like.’ They never met again: on 3 August, Jabotinsky passed away.[13]

One reason for Dohány’s closer relationship with Jabotinsky may have been that, although among his followers there were a significant number of far-right Jewish youth who sympathized with contemporary fascist movements, Dohány himself was always against fascism. Jabotinsky believed that there was no need to copy any foreign movement, whether fascism or communism. In an early article, Dohány presented international fascism as a hateful ‘blight’ that uses terror as a tool. Although at this time he was not a Revisionist, it is not unlikely that later he still harboured an aversion toward far-right ideology, and this could have been a point of connection between him and Jabotinsky.[14]

‘Jabotinsky believed that there was no need to copy any foreign movement, whether fascism or communism’

According to his memoirs in English, in 1940 Dohány participated in organizing the illegal immigration (Aliyah Bet). Ironically, not only did Reuven Hecht, the Revisionist financier, assist him, but also some secretly anti-Nazi employees of the German embassy in Belgrade, including, for example, a relative of Hjalmar Schacht, the former Nazi German Minister of Economics.[15] It is likely that this already attracted the attention of the German secret police. On 6 April 1941 Nazi Germany attacked Yugoslavia, and its ally, Hungary began its military operation on 11 April, during which, except for the Western Bačka region, it reclaimed some of the southern territories lost during the Treaty of Trianon in 1920. Novi Sad came under Hungarian rule again, the Zionist press was soon banned, and the movement found itself facing a much more hostile state than before. In June 1941 the Hungarian police arrested Dohány and handed him over to the Gestapo, who held him in Belgrade until December, where he was severely tortured before being deported. Dohány passed through several concentration camps, including Mauthausen, and returned home only in June 1945.[16]

After the liberation he was a member of the Yugoslav National Committee for the Prosecution of War Criminals, and then briefly moved to Budapest before leaving the country. His son, a chemical engineer, followed him in 1956. He settled in the United States, where he worked for a time in some position at the US State Department, and later worked as a college professor teaching law and philosophy (likely in Tennessee, which later made him an honorary citizen). According to a letter from 1963, he was learning Hebrew at that time—perhaps a characteristic comment from a highly assimilated Jew who turned to Zionism only as an adult.

In 1968, in his old age, he moved to Haifa, where he passed away in 1972 at the age of 89. Upon his death, Tomaschoff referred to him as ‘one of the pillars of Hungarian Zionism’—which was true, but mostly for the Hungarian-speaking part of the Zionist movement in Yugoslavia. The family issued a brief death notice: ‘The friend of Marmorek, the friend of Jabotinsky, has passed away.’[17] Indeed, Dohány was one of the most influential Hungarian figures in the Revisionist Zionist movement, and the lack of recognition of his biography (so far) has been a painful gap in the history of Hungarian Zionism.

[1] Budapest Főváros Levéltára (BFL), IX.282.b. 3530, and Tomaschoff Baruch, ‘Dr. Dohány Gyula emlékezete’, Új Kelet, 29 May 1972, 4.

[2] For the sources of this paragraph, see: Gábor Dezső, ‘Húsz év előtt’, Uj Kor (Timisoara), 17 Nov 1938, 5; and Kauftheil Ernő, ‘Egy csendes jubileum’, Új Kelet, 24 Feb 1958, 5; and Új Kelet, 19 Dec 1918, 5–6.

[3] Veszprémy László Bernát, ‘Zsidó, demokratikus, szocialista, anticionista’, Szombat, 7 Oct 2017, https://www.szombat.org/tortenelem/zsido-demokratikus-szocialista-anticionista.

[4] Dr Dohány Gyula, A zsidóság nemzetiségi mozgalma, A Temesvári Zsidó Nemzeti Szövetség kiadványai, 1. No, Temesvár, Uhrmann Henrik, 1919.

[5] Dévavári Zoltán, ‘Élet az új államban. A szabadkai zsidóság és az antiszemitizmus (1918–1939)’, Évkönyv 2014, Újvidék, Újvidéki Egyetem. 22–36, 26.

[6] Dr J Dohany, ‘Juden und serbische Presse in der Vojvodina’, Jüdisches Volksblatt (Novi Sad), Nov 24 1922, 1.

[7] Dohány Gyula, ‘Zsidó politika’, Haivri (Novisad), March 1923, 4–5.

[8] Vojislava Radovanovic, ‘Betar’, In: Jewish Youth Societies in Yugoslavia, 1919–1941, Belgrade, Jewish Historical Museum, 1995, 83–86, 83.

[9] Jabotinsky Institute (JI), A1–2/23/2.

[10] Népünk (Oradea), 7 Feb 1936, 12.

[11] Dr Julije Dohany, Die Wahrheit über Palästina und das jüdische Nationalheim, Novisad, 1936. A copy of the rare pamphlet can be found here: JI, P124–11/1/4.

[12] JI, A1–2/29/1; and Pejin Attila, A zentai zsidóság története, Zenta, 2002, 197.

[13] JI, A1–2/30/1.

[14] Dr Dohány Gyula, ‘A fascista mozgalmak közössége’, Bácsmegyei Napló, 24 Nov 1922, 1.

[15] JI, P124–3/29, see also P124–3/19 and P124–10/2.

[16] BFL IX.282.b. 3530.

[17] JI, G27–1; and Tomaschoff Baruch, ‘Dr. Dohány Gyula emlékezete’, Új Kelet, 29 May 1972, 4; and Új Kelet, 15 May 1972, 1.

Related articles: