A recent article by Géza Balázs linguist, folklorist and university professor in the conservative journal Kommentár examines the need for, and the possibilities of a Hungarian language strategy. According to Balázs, Hungarian academic institutions have so far neglected this area, which is quite regrettable in his view.

The piece starts by declaring that human language is the most important vessel of ideas, therefore every nation must cultivate its own. Balázs highlights that in the case of Hungary, language had and still has a crucial role in forming national identity. Therefore cultivating and protecting our language has outmost importance for Hungarians. This is why, according to the author, it is sad that support for this notion waned in the 1990s. He bemoans that many academics started to question the need for and legitimacy of language preservation efforts. This is especially regrettable, according to Balázs, because

one of the founding principles of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences was to support and cultivate the Hungarian language.

The professor describes how scholars, academics, and other public figures used to hold this principle dear. Apart from the past efforts of the academia, the author also recalls the 1905 government plan of creating a state bureau for language cultivation.

However, Balázs continues, after the end of the Socialist regime, a laissez-faire view became predominant, according to which cultivation of the language is useless, or even harmful. The proponents of this school argue that cultivation is not only unnecessary, but also curbs the freedom of people to use their own personal language as they see it fit.

Balázs argues that because of the decreasing academic support, a grassroots movement should emerge in language cultivation, coming from outside of academia, in order to preserve and strengthen the identity of Hungary.

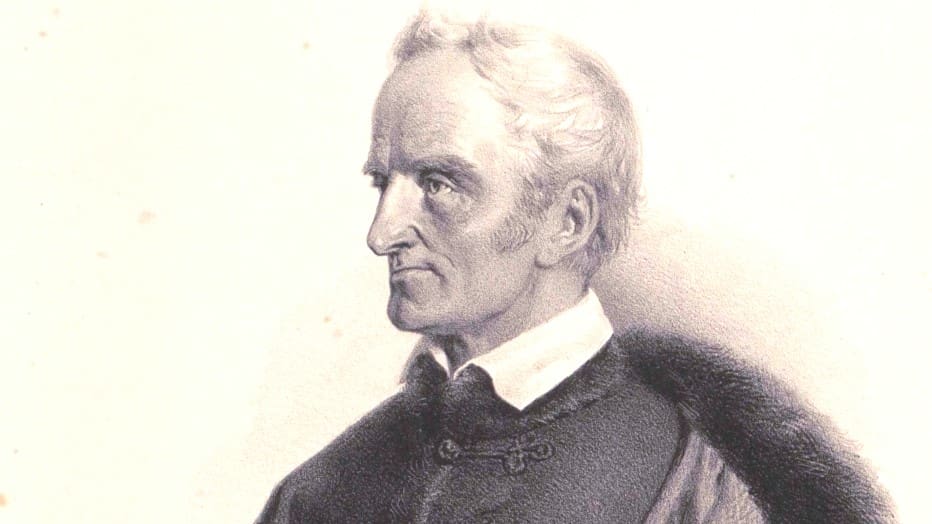

In his essay, Professor Balázs also highlights the difficulties Hungarians living beyond the country’s current borders are facing. He draws attention to the fact that the right to using their mother tongue is often trampled upon, and yet Hungarian is now a modern, developed language the use of which is not restricted to inside Hungary’s current borders. He also underscores that Hungarian is a language perfectly suitable for the discussion of complex scientific topics, not least thanks to a constant cultivation and renewal advocated and promoted by such great intellectuals as Ferenc Kazinczy and others.

The author concludes that Hungarian language is not directly threatened these days. However, he designates several perils which, although may seem to be small issues in themselves, still can be harmful when combined. Apart from political issues like globalization and political correctness, he identifies gradual language attrition as the most problematic. According to him, too many English expressions have made their way into Hungarian, and in addition, various professional jargons and bureaucratic language are becoming more and more complicated. According to Balázs, while there had been challenges to the Hungarian language before (for instance, the integration of the so-called ‘youth language’ of the 1960s), after the 1990s, the challenges multiplied. He points out that by now each social group has its own lingo, while globalization, digitalization, and other, outside influences also have an impact on the language. And, Balázs warns, Hungarian linguists are yet to come up with an answer to these challenges.

These complex challenges require a language strategy, Balázs argues, a strategy that can prepare Hungarians to deal linguistically with the challenges of the new world, including digitalization. Furthermore, he also suggests that it is also important to simply make the Hungarian language clearer.

In the last part of his essay, Balázs argues for the necessity of a practical language strategy. He reiterates that in Hungary thinking about the language is almost inseparable from concerns related to the nation, and patriotism. In his view, the strategy therefore must be coupled with an action plan. The professor explains that while cultivation and standardization are important, they should not be in conflict with the notion that each community, and the online world itself, have their own, distinct language variants. However, he stresses, communication between these segments must be made seamless. Furthermore, he stresses,

the correct understanding and knowledge of one’s own language is a pre-condition for learning foreign ones.

Therefore, until language cultivation is not upgraded, we cannot expect the knowledge level in foreign languages of Hungarians to improve, he concludes.

Balázs concludes that it is not enough to celebrate our language from time to time: a concrete actions plan as well as a broader strategy are needed to prevent its deterioration. The cultivation of a language is not something obsolete or retrograde, his article suggests, but instead, a still important task in which Hungary lags behind other nations.