When one thinks of the pagan beliefs of European peoples, it is the Greek and the Scandinavian mythologies that first come to mind. The reason is that the Greeks and the Scandinavians are in a sense lucky—unlike in the case of other nations, a large corpus bearing witness to their worldview has survived. Both the Greek Iliad and the Norse Edda have been extensively studied and taught about over the course of centuries, making an indelible impact on world culture.

The Hungarian case is, however, more complicated. Not only have no comprehensive literary pieces survived, but even a comparative reconstruction faces a significant impediment. Unlike the neighbouring Slavic, Baltic or other European pre-Christian worldviews, the Hungarian mythology, as well as the language, is of non-Indo-European origin. The Slavic peoples, although they do not have any written texts preserved of their ancient traditions, have the same cultural and linguistic roots as the Scandinavians. Hence, to a certain degree, the Slavic pre-Abrahamic worldview can be reconstructed based on the amply documented ones of their neighbours. When it comes to Hungarians though, such mental leap is hardly possible due to the unique history of the Magyars. Before settling down in the Carpathian Basin, they incorporated multiple north Eurasian beliefs and traditions, including Siberian, Uralic, Turkic and many others, which further hinders reconstructive attempts.

On the other hand, there is a silver lining to this special history: eventually, it created a unique blend of narratives, a richly woven tapestry like no other. Although Christianity has ultimately played a decisive role in shaping the culture and history of Hungarians,

the echo of the long gone and forgotten worldview of their forebears still reverberates in their folk stories and customs.

In addition, although no first-hand written sources have survived of it, thanks to the thorough scholarly efforts to reconstruct the ancient Hungarian worldview, we know quite a lot about the pre-Christian beliefs of the Magyars.

One of the central elements of the Hungarian shamanistic outlook is the idea of a sky-high, or world tree, or the tree of life (‘égig érő fa’ or ‘életfa’). This tree plays a strong role in the ancient Hungarian cosmology, as its different levels essentially serve as separate realms of the universe. On the top, higher entities, gods themselves live, whereas the middle realm serves as the place of Human’s existence, as well as the living site for various spirits and supernatural creatures. The lower realm, however, is reserved to lowly malicious beings, who created everything foul and bad for Humankind. The Turul bird, the Hungarian mythological avian which today serves as one of the nation’s symbols, resides on top of the tree and thus the Cosmos itself.

Despite clear resemblance to the Norse Yggdrasil, also known as the tree of life, which surprisingly also functions as the universe’s ultimate delineator and, even more interestingly, has a mythical bird on top as well, the Hungarian tree of life idea most likely does not derive from it; it is more probable that the two cosmologies have a common root. Both may be traced back to the unfathomably old shamanic practices of northern Eurasia, wherein only a shaman can climb up and down the tree, travelling between different worlds. This origin of this belief that shares and unites a dozen of cultures all around the world, not only Hungarians and Scandinavians but also native Siberians and northern American Indians, is probably untraceable by now, nonetheless it suggests a possibly shared pre-historic life and practices of these, now completely separate and distant nations.

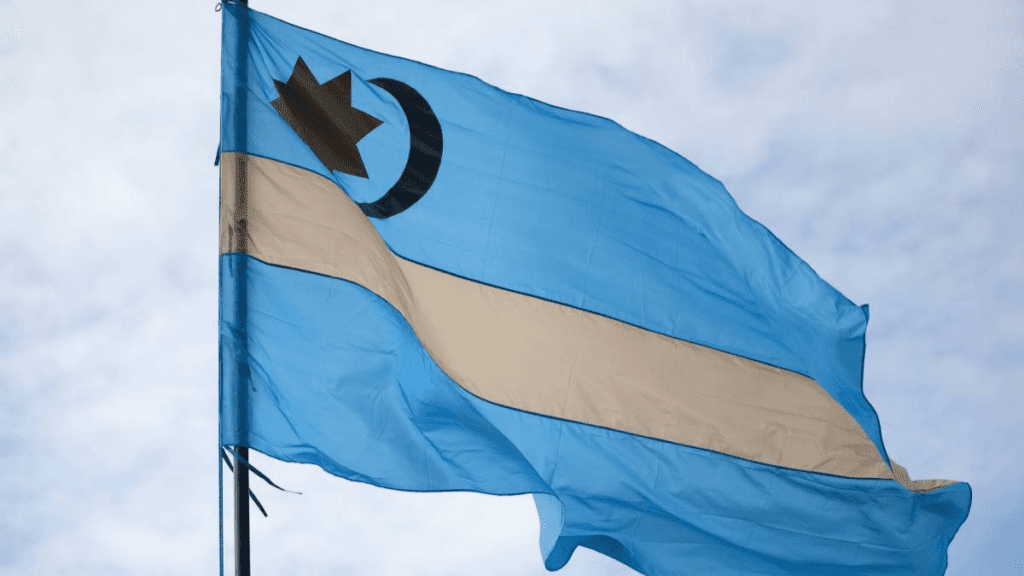

The sun and the moon were also located among the higher entities of the world’s tree canopy. These celestial bodies supposedly used to play an important role in folk magic, and their designations were found in Hungarian pre-conquest graves and mounds. This more than a thousand-year-old symbolism has survived to this day in the Szekler (Székely) culture, with the sun and the moon being represented on the Székely flag.

The bestiary of the Hungarian old belief system is as rich as those of its many known counterparts in other mythologies. The Wondrous Stag that, according to the legend, led Hungarians to the Carpathian Basin is among the most significant animals in the before-Christ Hungarian worldview. As in many other ancient myths of origin, the Magyars believed their ancestors had either been animals or turned into animals after their passing—a common trope among probably all world cultures, somehow deeply ingrained into our psyche. As recorded in the Gesta Hungarorum, the Árpád dynasty’s totemic ancestor was believed to be the Turul itself. There is also an abundance of many lesser creatures that populate the lower and the middle realm, such as the markoláb, a flying creature of immense size that consumes celestial bodies; dragons, who were responsible for bad weather and usually brought trouble to people, and many other—the world of ancient Hungarians was filled with all sorts of mystical beings.

As far as real animals are concerned, there are some that held a special place: positive or not necessarily so. A nomad nation, Hungarians used to hold horses in high esteem; hence the ancient Hungarian custom of equestrian burials similar to those of Indo-Europeans. In such a ritual, a deceased warrior would be put to the grave with his horse, previously sacrificed.

Other animals, however, had a clearly negative role. For example, the wolf, the adversary and competitor of humans for the precious livestock. The negative role of the wolf underwent such a strong process of aggravation that the name of this poor beast eventually became a curse in the Hungarian language (the current word for the wolf is ‘farkas’, whereas the curse word is ‘fene’). The name, although now devoid of its sacral meaning, used to mean an invocation of an evil spirit, a curse in its original, magical sense.

While Hungarian native beliefs may not have developed a robust tradition or philosophical foundation akin to Christianity, they nonetheless endured in various forms, partly merging into Christian practices, and have significantly contributed to the shaping of both Hungarian folk and high culture.

Related articles: