As far as the Turks and Hungarian history is concerned, it is regrettable that many people still only connect the two in terms of the ‘Ottoman subjugation’, which represents an undoubtedly tragic period in our country’s history—from a Hungarian perspective. But the ‘Ottoman Turks’ (originally: Oguz Turks), who converted to Islam later, were by no means the only Turkic people that the Hungarians encountered during their long history.

History and Kinship

The Hungarian and Turkic people (or rather, peoples) are connected in many cultural and even genetic ways. (In my previous article on the broader subject I already highlighted some genetic facts.) In December 2023, the Hungarian and Turkish governments launched the Hungarian–Turkish Cultural Year 2024, to mark the 100th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries, which indicates that cultural relations have never been severed, on the contrary, seem to be ever more strengthening.

The Byzantine emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus called the Hungarian conquerors ‘Turks’, and the sons of the House of Árpád (Turul gens in medieval Hungarian sources) were later called ‘Princes of Turkey’ by the Byzantines.[1] In the origin myth of the Hungarian royal dynasty, the ‘Turul bird’ is also of Turkish origin, as the symbol of the Sky and of the supreme God of Turkish myths, where it appears as toġrïl or toğrul.

It is likely that even before the conquest, the Hungarian tribal confederation, already including Bulgarian and various Hunnic people, had already assimilated several additional ethnic elements of Turkish origin. The most important of these were the Kabars (or ‘black Hungarians’) who significantly increased the numbers of the conquering tribal confederation.

The language of the European Huns may have been mostly Turkic (maybe Oguric, a branch of the Turkic language, which, except the Chuvash language, mostly died out) and the Onogur alliance—to which the Hungarians probably lived in close proximity—may have also contained a significant Turkish element. Most of the names of the Conquering leaders have a Turkish etymology, as do the names of dignitaries. Even after the conquest led by Árpád, the Hungarians welcomed ethnic Turks in abundance: mainly Pechenegs and Cumans, and to a lesser extent the Oguz called ‘Úz’ in contemporary sources.

The culture of the Turkic peoples permeates the Hungarian language to this day. According to some researchers, there are still between 300 and 500 Turkish words in the Hungarian core vocabulary, and in the past, there may have been even more words of Turkish origin. There are also quite a few grammatical similarities.

The Christian Hungarians who settled down in the Carpathian Basin had the closest relationship with the Cuman tribal association (the Cuman–Sari– Kipchak tribal confederation), the fate of which was closely intertwined with that of the Hungarians. Anonymus, the most important medieval chronicler of historical Hungary (LINK) names fifteen Cuman people in his Gesta Hungarorum (of which seven are tribal leaders), although this may be just a reflection of the dominant narratives of the thirteenth century in which the chronicler lived. Hungarian medieval studies usually include the also Turkish-speaking Kabar (and/or Pecheneg) tribes and chieftains as the ‘Cumans of Anonymous.’ [2]

The best-known Cuman ruler is Khan Khuten (Kötöny), a ruler who was accepted into the Kingdom of Hungary (and then murdered) just before the Mongol invasion, but we could also mention Basarab, who ruled in Bessarabia, the present-day Wallachia region, who according to some historians may have been related to the Hunyadi family.

It is certain that the Cumans had arrived in several waves already earlier, in addition to Kuthen’s Cumans. Some historians believe that the Palóc ethnic group in north-eastern Hungary is also of Cuman origin. (In Slavic sources, the Cumans are called ‘Polovetsy.’)[3]

After the initial struggles and difficulties, the Cumans were eventually integrated into the body of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary, adopting Christianity, but not forgetting their combat tactics and steppe life. The dynasty of Cuman princes became related to the Árpáds through Elizabeth the Cuman (probably the daughter of Cuman chieftain Seyhan).

Where Did these Turkic Peoples Originally Come From?

It is likely that some of the Huns—the European Huns for sure—spoke some kind of Old Turkic language or dialect. However, the word ‘Turkish’ is of later origin: it probably comes from the name of a tribe or genus. The word ‘Turk’ (in Hungarian, Türk) could have meant ‘strong, brave’ (although linguists do not agree on this) and the tribe that first called itself Turk must have been a component of the Asian Hun—Xiongnu—Empire. This is also mentioned by one of the origin stories of the Turks, according to which the Turks are the descendants of a Xiongnu shanyü. (‘high king’)

The Turkic—or as it is also referred to, the ‘Gokturk’ (Gogtürk) Empire (also known as the First Turkic Khaganate)[4]—was created as a huge and well-organized empire in the 6th century AD (after 552) in the grassy steppes and mountains of Eurasia. The empire was founded by two brothers: Bumin and Istemi, who defeated the Asian Avars called ‘Juan-juans’ in Chinese sources. Although the Empire only existed in a unified form for about a hundred years after which the alliance of the Chinese and the (also Turkish speaking) Uyghurs destroyed it, this first Turkish Empire expanded with greater force, united more peoples and expanded further towards the West than any other a former state of steppe origin.

Most of today’s Turkic peoples probably occupied the area they live in today during the westward expansion of the Gokturk Empire (or as a later continuation, a sub- or post-state of it). The adjective ‘Turkic’ only spread long after the age of the First Turkish Empire to the names of peoples and languages that are linguistically and culturally related to each other, such as the culture and language of the Kazakhs, the Kyrgyz, or the Anatolian Turks (later called the Oguz Turks). It is possible that these diverse tribes and peoples were once all parts of the First Turkish Empire.

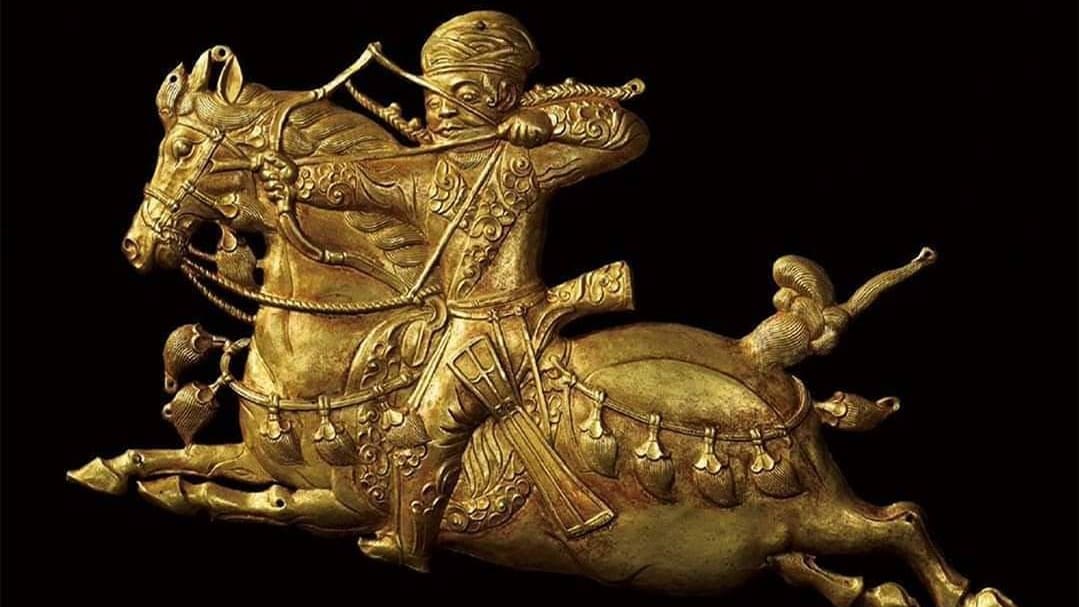

The Turkish Empire was highly civilized. Its ruling dynasty was the clan Asina, originally engaged in blacksmithing: metalwork was traditionally associated with sacred, symbolic concepts on the steppe. In addition to the fact that the quality of Turkish weapons and Turkish armour was excellent, the making of weapons also had a ritual character: according to some researchers, the Hungarian word ‘tárkány’ (the original meaning of which is probably blacksmith), the name of a Kabar tribe, also preserves the memory of this, in denoting belonging to the aristocracy. (tarẖan in Iranian sources, tarχan in Turkic languages, and the Mongolian word darqan are all connected to the titles of high nobility.)

The centre of the empire, located in present-day Mongolia, was called ‘Otuken’ (Ötüken in Hungarian spelling), referring to the mythical homeland of the Turkic peoples, the ‘centre of the world.’ According to sources,[5] Otuken or Otugen could also be the name of the centre of the Asian Huns. According to the imperial-religious tradition, Ötüken means the ‘axis of the world’ (Axis Mundi); at the same time, the World Tree rising from the spheres of hell to the sphere of heaven. It is symbolically also the ‘place’ where the souls of the dead leave the earthly world, and from where the migrations of tribes start and return. The World Tree is closely related to the worldview of Tengrism: this shamanistic religious tradition may have formed the basis of the worldview of most steppe peoples (not only the Turkic peoples), thus, perhaps the Hungarian ancestral religion before Christianity could also be connected to Tengrism.

The shaman (‘Kam’ in the Turkic tradition) can travel up the World Tree to the sacred space; among its branches, the souls to be born are waiting in the form of birds. The World Tree, according to the Hungarian ethnologist and orientalist Vilmos Diószegi, has nine branches or ‘levels’. These nine branches are also represented on the shaman’s drum in the Altai region.[6]

According to Gokturk inscriptions, the Turkic ruler, the khagan, exercises absolute power in the empire like the sky god, so the earthly ruler is the image of the heavenly deity. The khagan is in constant contact with the deity through the kut-soul (‘spirit-soul.’) A Byzantine envoy, who was sent to the Turks, writes about the court of the ‘yabgu’ (a vice-khagan of the Turkic Empire). According to some scholars, the title yabgu was also preserved in the Hungarian name Géza, which in the Western Turkic language developed into the form of djebu/dzevu, while Géza's name may have sounded as ‘Dzeucha/Dzevicha’. The Byzantine chronicler also speaks about a golden throne that can be moved on a wheel, of wonderful workmanship, and the clean and luxurious nature of the clothes of the Turks (as in the case of the Hungarian Conquerors, the Arab travellers did). Chinese sources also report on how culturally developed the empire was. So, we can safely say that the First Turkic Empire, for as long as it existed, was one of the largest powers of the steppe, and its organization and size could only be rivalled by Genghis Khan’s later (also only briefly united) Great Mongol Empire.

[1] ‘And Hungarians are one kind of the Turks,’ quoted in Görgy Szabados, ‘Árpád fejedelem. Történet és emlékezet’, Magyar Tudomány 11/2007, http://www.matud.iif.hu/07nov/09.html, accessed 17 March 2024.

[2] Loránd Benkő, Anonymus kunjairól.

https://acta.bibl.u-szeged.hu/65206/1/1995_kelet_es_nyugat_kozott_039-067.pdf, accessed, 17 March 2024.

[3] See István Majoros, Palócok földjén.

[4] Göktürk, or ‘Sky’ Türk, expresses the special connection of the empire's ruling dynasty to Sky-Father Tengri, the main god or absolute god of shamanistic Turkic primordial religion. (The meaning of the Hungarian word ‘kék’ (blue) is the same as the Turkish word ‘gök/kök’.)

[5] Cengiz Alyılmaz, ‘Karı Çor Tigin Inscription’, International Journal of Turkish Literature Culture Education (in Turkish), 2/2 (2), 2013, 1–61.

[6] See Vilmos Diószegi, Samanizmus (e-book), https://www.mek.oszk.hu/01600/01639/01639.htm (Last accessed, 2024. 04. 17.)

Related articles: