Since the beginning of the invasion, a campaign has been conducted in the West to boycott Russian culture, as a form of punishment for the Kremlin’s aggression. Prestigious international cultural events, such as the Dublin and the Honens International Piano Competitions ruled to exclude Russian citizens from competing. Similarly, Wimbledon also introduced a blanket ban on Russian tennis players, a decision that echoed Wimbledon’s 1940s choice to bar German and Japanese players from entering the games due to their apparent ‘collective guilt’ in World War II.

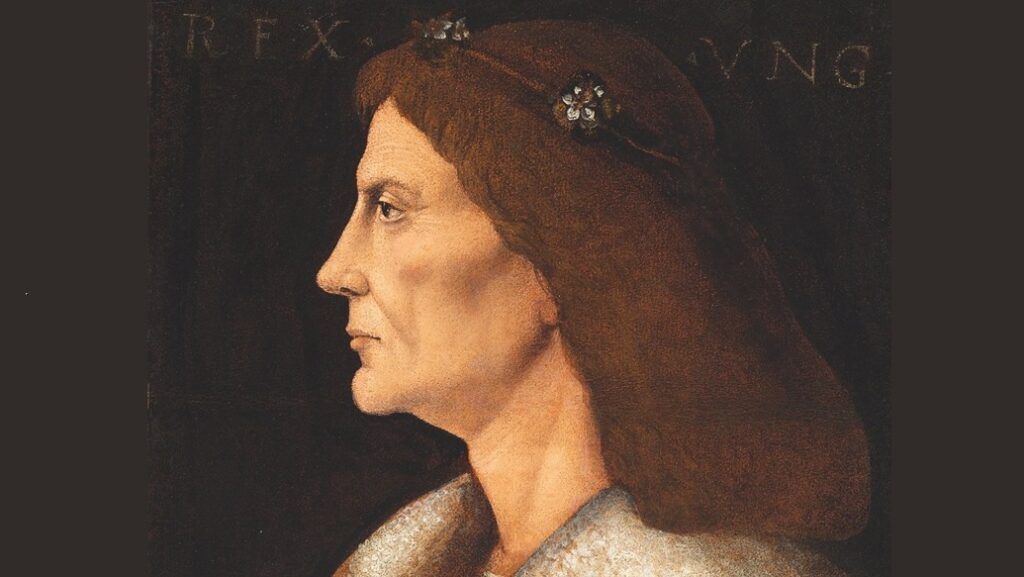

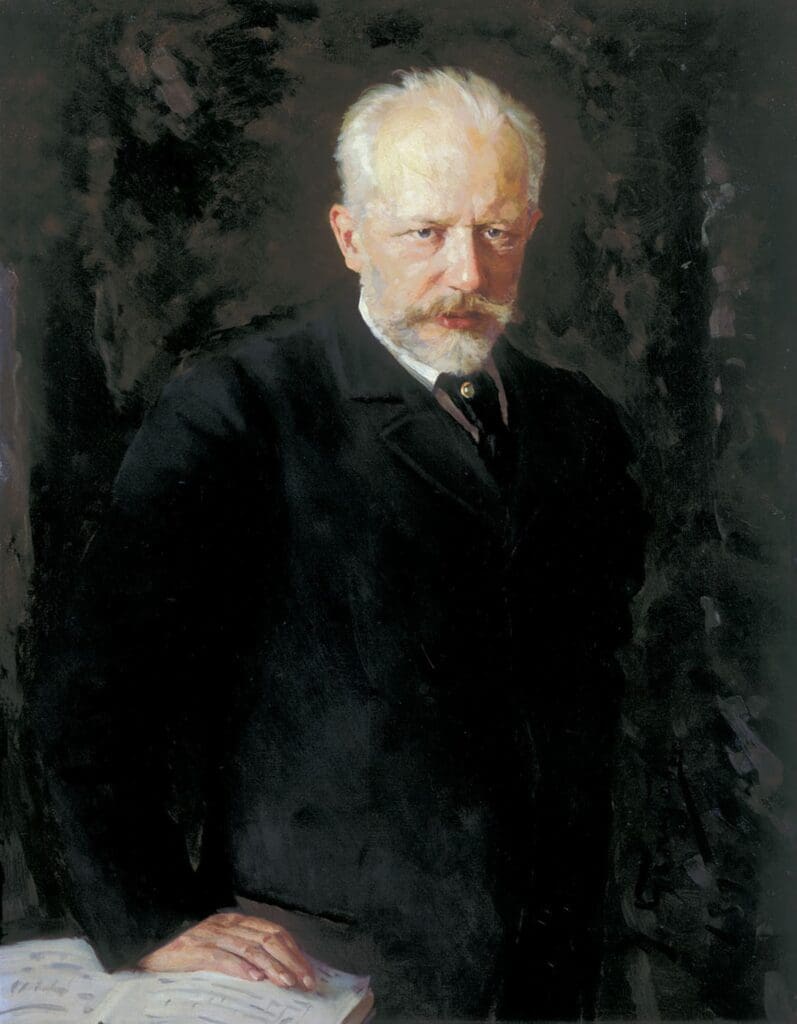

Tchaikovsky the Culprit?

Tchaikovsky’s work was subject to similar nonsensical censorship in the Western world—the Cardiff Philharmonic Orchestra removed musical pieces by Tchaikovsky from their programme. Pavel Sorokin, who was supposed to conduct Swan Lake in the Royal Opera House in London, was disinvited due to his Russian citizenship, while the performances of Moscow’s Bolshoi Ballet were also cancelled. The performance of Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov was scrapped in Poland. So far, only Fyodor Dostoevsky managed to escape ‘cancel culture’—due to the international outcry, the University of Milano-Bicocca eventually did not postpone its lectures on the great Russian writer. Netflix, on the other hand, stopped the production of an adaptation of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina due to the war, as we have reported earlier. It is crucial to recognise that these instances of discrimination are not targeting the Russian state, but Russian contributions to world culture. Russian artists of both the present and past are being targeted and cancelled simply for belonging to a nation whose current leader started a war.

A crowd in Exeter also attempted to cancel the performance of a piece by Tchaikovsky.

Incidentally, the conductor at the concert was the Hungarian Gergely Madaras.

The conductor, whose grandmother was of Russian heritage, reminded the audience of the great cultural value that Tchaikovsky’s and other Russian artists’ work carry. He concluded his speech with the following remarks:

‘Today, this masterpiece is a reminder of how fragile human life is. As a pacifist and a humanist, I reject all violence and all forms of aggression. I believe that no political interest can be more important than human life. I know Tchaikovsky would agree with this, too.’

The audience appreciated his views, and the piece by Tchaikovsky was performed with great success. Had conductor Gergely Madaras not stood up for Tchaikovsky, however, the performance would have been cancelled.

As Gergely Madaras reminded the audience, banning artists and opposing the aggression of a state are two different things.

While removing the Russian flag and not playing the Russian anthem in international sports competitions is understandable, prohibiting Russian athletes from competing even under a neutral flag is discrimination based on one’s passport. Similarly, disinviting Russian delegations from the Cannes Film Festival is again a justifiable decision as their state has committed atrocious acts—but just because official delegations do not attend the Festival, individual directors or actors should still be able to do so.

Hungary Chooses not to Discriminate

Unlike most European countries, Hungary does not engage in virtue signalling, punishing Russian culture or individual Russian artists for the invasion. Artists of the present have not been cancelled for their alleged responsibility in the war either. The cultural heritage created by Russians is being performed in Hungarian cities just like before the war.

Concerto Budapest, one of the most prestigious Hungarian Philharmonic Orchestras, is now working with Mikhail Pletnev, the Russian composer and pianist. Sergei Prokofiev’s world-famous operatic version of Tolstoy’s War and Peace was performed for the first time in Hungarian theatres in January this year. The Hungarian State Opera House, which has been preparing for the performance for five years, designed the play’s scenery based on the interior of Saint Petersburg’s Hermitage. Director General of the Hungarian State Opera House Szilveszter Ókovács has said that the performance of War and Peace is just the beginning, and he hopes to embed more of the greatest achievements of Russian and Soviet music into Hungarian culture. Not only the opera version of War and Peace, but Tolstoy’s book, too, is experiencing a revival in Hungary: after 70 years, a new translation of the great Russian novel was released earlier this year.