Although Tibor Baranski belongs to the lesser-known heroes of the darkest days of 1944-45, his heroic deeds are no less significant than those of Raoul Wallenberg, Angelo Rotta or Margit Slachta, who also risked their own lives in order to save innocent Hungarians from certain death. While the names of the famous rescuers of persecuted Hungarian Jews are commemorated in the names of boulevards in Budapest along the Danube, Baranski’s memory has yet to be revived, even in his native land, Hungary. A new documentary titled Until Death (Mindhalálig in Hungarian) finally fills that gap and introduces Baranski’s history and his heroic deeds to a wider audience.

In Hungary, the history of the Holocaust is unique but just as tragic as in other Central and Eastern European countries impacted by German occupation and Nazi ideology. The Kingdom of Hungary, mutilated by the disgraceful Treaty of Trianon, had a high percentage of Jewish population. This was partly the result of the successful assimilation that started in the peaceful years of the 19th century, and partly due to the fact that the Kingdom of Hungary, or the broader Habsburg Monarchy, just like Germany until the thirties, reached a high level of emancipation of its Jewish citizens, as opposed to Eastern Europe, where antisemitic pogroms were a commonplace occurrence. Of course, antisemitism was prevalent in Hungary too, and steadily growing after the Great War, especially intensifying during the economic hardships of the Great Depression. The oppression and the restriction of the rights of Jews in Hungary became more severe especially after Hungary entered World War II on the side of Nazi Germany. However, unlike in other parts of Nazi-occupied Europe, mass deportations or murders of Jews did not take place and Jews in Hungary were able to live in relative (relative being stressed here) safety until German troops invaded Hungary in March 1944 and installed their puppet Arrow Cross government.

At the time of the German invasion, Hungary had the largest remaining Jewish population in Europe,

numbering more than eight hundred thousand. When the Germans took over, life changed for the worse for Hungarian Jews almost overnight. The Nazi occupiers, in cooperation with their Hungarian collaborators, organized with stunning speed and effectiveness the mass deportation of Hungarian Jews to the extermination camps. In a few months’ time, by the summer of 1944, about 430,000 Hungarian Jews, almost the entire Jewish population outside the capital, were sent to the death camps. For most of them the destination was Auschwitz, where 80 per cent were immediately murdered and the rest faced certain death. By the time in early July 1944, less than three months after the German occupation, Miklós Horthy, the powerless regent of Hungary, ordered a halt to the deportations under foreign pressure, the entire Jewish population of the countryside was gone.

This, however, did not mean that the Jews in Budapest were safe. By June the Jewish residents of Budapest were rounded up and forced to relocate to the so called ‘yellow-star houses’ (approximately two thousand buildings designated with a yellow Star of David). In late November, all Jews were moved to the Jewish ghetto created in the 7th district, in preparation for their deportation to the death camps. Although their deportation was prevented by Horthy, the life of the Jewish population in the capital city was in constant mortal danger after the Arrow Cross takeover of October 1944. The Arrow Cross death squads carried out raids and mass executions in Budapest at a time when the Hungarian state basically ceased to exist and as the Soviet Red Army was advancing towards Budapest. Random killings happened on a daily basis in the streets of the Hungarian capital. The rampage cost the lives of thousands of Hungarian Jews in Budapest. As no official record of those executed was kept, there are no exact figures, only estimates of the number of the murdered Jewish citizens, the rampage most certainly cost the lives of thousands of Hungarian Jews in Budapest.

There were amazing personalities who not only risked, but outright sacrificed their lives to save as many Jews as possible.

The most famous of them is the Swedish diplomat, Raoul Wallenberg, who after having saved an estimated 70,000 Hungarian Jews in Nazi occupied Budapest, was detained by the Soviet Red Army in Hungary and ultimately died in Soviet captivity in the USSR.

Beginning in 2010, the Hungarian government started renaming the boulevards along the banks of the Danube after famous rescuers of Hungarian Jews. The banks of the Danube are symbolic because they were the scene of mass executions: the Arrow Cross militiamen would line up innocent civilians, including women and children, by the bank of the Danube and would shoot them into the water. It is estimated that between ten and fifteen thousand Hungarian Jews lost their lives this way.

There are streets along the Danube named after Count János Esterházy, Margit Slachta (Schlachta), Apostolic Nuncio Angelo Rotta, Lutheran pastor Gábor Sztehlo, Friedrich Born, Raoul Wallenberg, Nina and Valdemar Langlet, Henryk Sławik, Carl Lutz, József Antall senior, Jane Haining, and Sára Salkaházi (Schalkház). Heroic, sometimes unusual or accidental heroes, who found their calling and did their utmost, often sacrificing themselves to save thousands of innocent lives regardless of their nationality or religion.

But one name is painfully missing from the list above: that of Tibor Baranski.

The Baranskis were originally a Polish aristocratic family, whose surname used to be spelt Barański. Tibor Baranski’s ancestors moved to Hungary from Poland in the 17th century.

Tibor Baranski saved the lives of no less than three thousand Hungarian Jews according to Yad Vashem in Israel, but the actual number could be as many as twelve to fifteen thousand. Baranski himself knew precisely the number of people he was helping because he was the one who coordinated the food and water deliveries to the Papal protection houses where Jews were put up in Budapest.

The exciting hybrid documentary that uses fictional and animation elements as well besides the traditional documentary style, tells the story of Baranski in a captivating way. Baranski was born in 1922 to a devout Catholic family. During WWII, he was studying at the seminary in Kassa (currently called Košice in Slovakia) preparing to be ordained as a Catholic priest. He was only 22 years old when the allied bombings and the Soviet advancement made life impossible at the seminary and he returned to Budapest in September 1944. Upon returning to the capital, he saw the horror of everyday life. He was confronted by the vulnerability of the Szekeres family, a Jewish family who lived in his neighbourhood and were close friends of the Baranskis. They convinced the young Baranski to try to get official papers (so-called Shutzpasses or ‘protection documents’) from the Apostolic Nunciature (the Embassy of the Vatican in Budapest) to prevent them from being deported. These official papers issued by neutral countries that maintained diplomatic relations with the collapsing Hungarian government in 1944 meant the difference between life and death for the Hungarian Jews. The Arrow Cross Nazi puppet regime installed by the Germans headed by the insane ‘nation leader’ Ferenc Szálasi had no international credibility. The diplomatic presence of neutral states was critically important for Szálasi and his gang of thugs to achieve a semblance of international recognition, which they did not want to jeopardize because of the of Hungarian Jews.

The twenty-two-year-old Baranski, barely an adult, showed enormous courage.

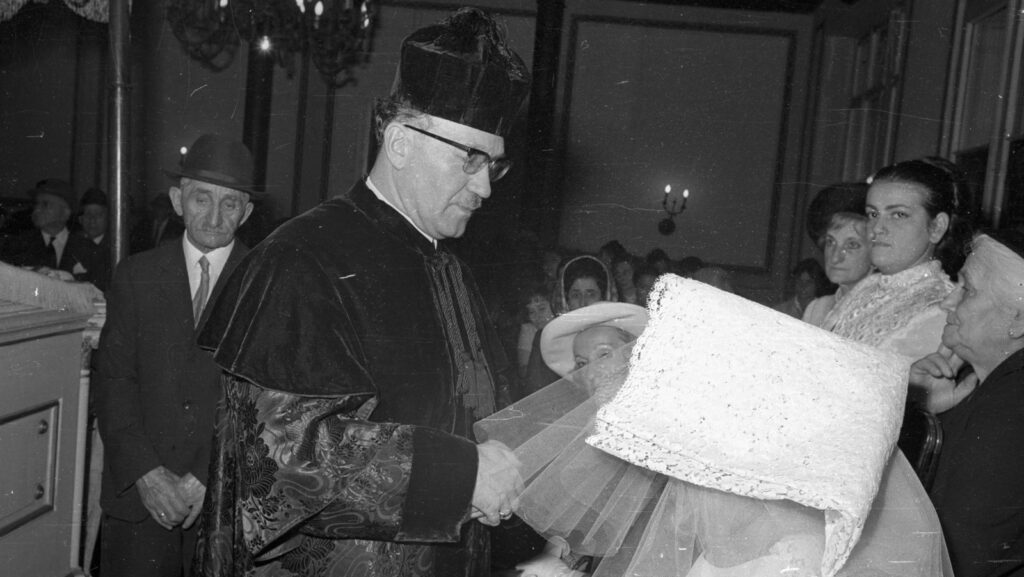

A man of strong faith, a devout follower of Christ, who in his own words got his strength from the Holy Spirit, went to the Apostolic Nunciature. Dressed in his priest’s robe, simply walked past the guards of the embassy and went straight into the office of Angelo Rotta. No one stopped the young man in his priest cassock walking confidently in the embassy building. The nuncio was more than surprised by the unannounced visit of this young seminarist. He asked for the issuance of nine letters of protection, which were granted, and which placed the Szekeres family under the protection of the Vatican and eventually saved their lives. Young Baranski saw that what he was up to worked and encouraged by the success, when he went back to pick up the protection papers for the Szekeres family, he asked the aging and cautious nuncio to go all-in: issue far more letters of protection, eventually in the thousands, to save as many lives as possible. Baranski played it big. He understood that the cowardly Arrow Cross thugs and the German occupiers only understand the language of strength, and he often showed up at the Jewish ghettos or the yellow-star houses with Vatican papers in the nuncio’s majestic Rolls Royce flying the Vatican flag. Baranski worked day and night for over two months. He did not care about anything except saving as many people as he could, as a man who had a calling that he accepted. A true Christian, he understood the fundamental teaching of Christianity: that all humans were created equal under God in His image:

Genesis 1:26 ‘Then God said, “Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness,“… 27 So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.’

Rotta was impressed by the braveness and courage of Baranski. Baranski spoke native level German that made him an effective negotiator with the German occupiers. Two weeks into his new role, Rotta appointed Baranski the executive secretary of the Vatican’s Jewish Protection Movement in Hungary, serving as a direct emissary of the Papal Nuncio. Baranski became the head of the Jewish Protection Movement on behalf of the Vatican and coordinated with the other embassies (Sweden, Switzerland, Portugal and Spain) active in saving Jews in Budapest. In only nine weeks, Baranski helped thousands of Hungarian Jews to survive certain death.

Normally a man like Baranski should have been honoured by his country, but he was not looking for worldly recognition. For Hungary, the liberation from Nazi occupation was followed by Soviet occupation. The Nazi demon was replaced by the Communist demon. The attempt at democratic governance in post-war Hungary was extinguished in short order and the country slipped into a Stalinist reign of terror from 1948.

Baranski quickly received ‘appreciation’ from the Soviet Red Army for saving thousands of Jewish lives: he was arrested by the ‘liberators’ on 30 December 1944 and sent on a 16-day, 160-mile death march towards a Soviet labour camp, during which he ate only four times. He was saved by a compassionate guard, so he eventually made his way back to Budapest by Easter 1945. As Communist oppression became more brutal, Baranski was arrested again in 1948 for being a ‘reactionary’, because he was one of the organisers of student-led demonstrations at Pázmány Péter University in Budapest where he was completing his graduate studies in theology and philosophy. In a communist-style show trial, he was sentenced to nine years in prison. He was sent to Vác near Budapest, where high-value political prisoners were kept. Baranski was regularly tortured, humiliated, and disgraced by his communist torturers. The goal of the communists was not to kill him but to break him with torture. In fact, he was even told by his torturers that he would die only when ‘he is allowed to die’. But Baranski didn’t break because God was with him, and again, just like in 1944, had plans for him. He was released on amnesty after Stalin’s death in 1953, after having spent 57 months in prison.

Three years later, in the autumn of 1956, Baranski joined the freedom fighters of the Hungarian Revolution.

As the head of the Red Cross in Buda he was again helping fellow Hungarians. He was sent to Vienna to negotiate international assistance for the Hungarian Revolution when the news came in early November 1956 about the Soviet Red Army’s invasion of Hungary. Baranski was messaged in a way that he understood in no uncertain terms: better not to return home, because the Soviets were again after him, returning to Hungary would have meant death. He chose life and spent time in a refugee camp in Rome. In Rome, Baranski reconnected with his old friend, Angelo Rotta in the hope that they could persuade Pope Pius XII to issue a public condemnation of the Soviet invasion of Hungary. This time, however, Baranski and Rotta did not succeed. The man originally preparing to become a priest met the love of his life in Rome, the daughter of a Hungarian family persecuted and dispossessed by the communists. He married Katalin Kőrösy in 1957, who was one of his English students in the refugee camp in Rome. The couple moved to Toronto, Canada in 1957 and then to Buffalo, New York in 1961, where the family settled with their two sons and daughter.

In 1979, Baranski was named as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem, the title given by Israel to non-Jewish individuals who risked their lives during the Holocaust to save the lives of persecuted Jews. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter appointed Baranski to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Council. But his name was erased from the collective memory in Communist Hungary. A man of strong Catholic faith, a true anti-Communist and 1956 freedom fighter, he would never warm up to Kádár’s ‘soft’ dictatorship. His deeds were recognized by his native country only in 2013. His only reward for the risks he took, he said, would come from God if he was deserving. ‘I only did what God demanded of me. I am only a useless servant of God,’ Baranski said.

Tibor Baranski died in 2019, at the age of 96 in Buffalo, where he is buried next to his beloved wife, Katalin. His memory and legacy are preserved by his two sons, Péter Forgach, born and raised in Hungary until age 11 and adopted from the previous marriage of his wife, and Tibor, Jr., born in Toronto who has never lived in Hungary. Both Péter and Tibor are fluent Hungarian speakers—Baranski never forgot his roots and remained a true Hungarian until his death, only speaking in his mother tongue with his children.

Mindhaláig, the 46-minute documentary runs two parallel stories from the dark days of late 1944 Budapest:

that of Baranski, and of a defrocked Catholic priest, the Arrow Cross monk Father Kun (known as Kun páter in Hungarian), a psychopath who tortured and killed hundreds of innocent Hungarian Jews while preaching about Christ and holding masses at the Városmajor church. The docufiction/animation documentary directed by Gergely Mózes not only introduces the stories and the personal development of Baranski and his antagonist Kun, two young priests (although Kun was only a self-appointed preacher as he had been expelled from the Order of Friar Minors), by re-enacting the events of 1944, but also shows the difference between good and evil, godly and ungodly, and the totally different paths people can take under extreme circumstances. One sacrifices himself to save others, inspired and led by God, while the other uses chaos to live out his perverted and megalomaniac instincts, playing God.

One of the morals of the Baranski story is that Nazis and communists are just two faces of the same evil one has to resist and fight. As Baranski said in an interview, ‘there was no difference’ between them, and ‘Hitler and Stalin could be two cherries on the same tree’.

Mindhalálig premiered on the Hungarian cable television channel Hír TV on 23 September 2022. Let’s pray that Baranski’s story reaches many more people and that sooner rather than later, a street along the Danube in Budapest will commemorate his name, as those of other heroes who saved lives during the Holocaust.