Typically, we don’t notice these connections, but there is a myriad of aspects that bind us to our ancestors. Especially in the world permeated with liberal individualism, we do not normally think that almost everything that makes us who we are, be it our pigmentation, height, susceptibility to diseases, reaction time or tolerance to extreme temperatures, can be traced back to time immemorial. We carry the past with us all the time, but not merely in our bodies, but also in how we think and express our thoughts, and the very language we speak. If your native language is of European origin, it can most likely be traced back to the Proto-Indo-Europeans, Bronze-Age equestrian nomads who shaped the Western and the entire human civilization.

If you read Hungarian Conservative regularly, you must be aware by now that the Hungarian language is a progeny of the Uralic language family—an entirely distinct linguistic group with a separate historical trajectory from that of the Indo-European languages that all of Hungary’s neighbour nations speak. However, for all intents and purposes, Hungarians are a European nation, and according to various estimations, up to one third or even half of the Hungarian vocabulary is attributed to Indo-European influences.

The Yamnaya Kurgans

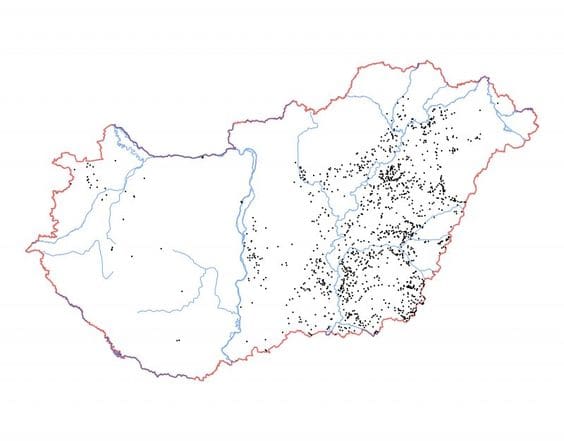

Moreover, the Hungarian landscape is dotted with the legacy of those who serve as the ancestors, be it in physical or cultural aspects, for all Europeans. Therefore, it is worth exploring the physical heritage left by the migrations of Indo-European peoples, which can be observed in the Hungarian countryside.

Around 3100 BC, the people that gave rise to the languages that are today being spoken by 46 per cent of the modern world’s population began to move westwards, migrating from their homeland in modern-day southern Ukraine and Russia. The Yamnaya people, as they are called by scholars, which means ‘relating to pits’, were a patriarchal, nomadic cattle-herding group, known to most likely have been the first humans to ever domesticate horses—an advantage that, combined with their pioneering usage of the wheel technology, was crucial for their success. These inventions transformed Eurasia from a series of disparate, unconnected cultures and civilizations into one system, characterized by constant interaction, technological exchange and the sharing of ideas. As a consequence of these transformative processes, thousands of years later, this manifested in the ascent of Western civilization and the spread of the languages descended from the Yamnaya across the globe.

As they reached the Carpathian Basin and the Danube valley, they began transforming the landscape of their newly acquired home. One of the iconic characteristics of the Yamnaya was their practice of erecting kurgans, also called tumuli in English, that is, burial mounds for the deceased of higher status. Their purpose was not only to honour the dead, but also to mark territory, as these mounds were probably dozens of metres in height, dominating the landscape.

The tallest Yamnaya kurgan in Hungary—and in Central-Europe— is the 12-metre-high Gödény, Mound near Békésszentandrás, Békés County. Considering the erosion by wind and water over the centuries, it may have easily been significantly higher originally.

The Gödény Mound. VIDEO: Petőfi Túrakör/Facebook

Inside these burial mounds, the deceased person was placed often in a foetus position and accompanied by animal offerings. The deceased was covered with ochre and luxurious goods were placed near them. Occasionally, the highest ranking members of the tribe would be buried with complete wooden wagons, indicating how important these means of transportation were for the nomadic Yamnaya.

Most of the time, the honour of being buried in such a grave was reserved only for high-status men, but female burials have also been discovered, indicating that despite the male-centric and bellicose nature of this culture, women could achieve prominent status as well.

As far as the symbolic importance of these mounds is concerned, some modern-day conservatives might find the meaning behind the kurgans very appealing. Alin Frînculeasa, archeologist researching the Yamnaya Kurgans of the Danube valley, wrote the following with regards to the subject:

‘[The barrow] seems a monument, and at the same time, a representation of the ideological power of this intrusive group. The establishment of lineage could ensure the passage in time and space of the unity of tradition and the relevance of ideology. At the top of the social pyramid stood a male figure symbolically endowed with the power of representing the continuity, stability, cohesion and unity of society…The homogeneity of this funerary phenomenon was visible until the end of the evolution of this tradition. We can assume that heredity/descendance was an important landmark in the Yamnaya society’.

Why Kunhalom?

Thousands of years later the Carpathian Basin was conquered by the Hungarians. Later, in the 19th century, the mounds sparked the interest of historians and archaeologists. As Hungarian funeral rituals were not known to have involved building a hill for the dead, Hungarian scholars initially attributed this practice to the Cumans, who arrived in the territory of the Kingdom of Hungary a couple of hundred years after the Hungarians had moved in. As a result of this wrong deduction, the term ‘kunhalom’ (meaning Cuman Hill) was coined to describe the mounds, possibly by 19th century linguist and historian István Horvát.

The Fate of the Kurgans

Interestingly, once the Christianization of Hungary began, and Saint Stephen ordered to build churches all across the country, the Yamnaya mounds were often selected as sites. This added a new cultural layer to the ancient kurgan mounds and enriched the cultural landscape of Hungary even more.

Unfortunately, due to erosion, their use as public places, sentinel posts or for agricultural purposes, thousands of the mounds have been destroyed over the course of centuries. Thankfully, thanks to scholarly interest, and the recognition of their unique historical value, the mounds acquired highly protected status from the state already before the regime change. In 1982, the Vésztő-Mágor Historical Site and Museum was created, to showcase the history and the excavated remains of the ancient burial mounds discovered near the site.

Beyond the aforementioned points, there exists additional Yamnaya influence on Hungary. Namely, there is a discernible presence of Yamnaya genetic markers in the entire Central-Eastern European region. While Hungarians may not have inherited as much Yamnaya DNA as Scandinavians, there is still a significant genetic commonality that links Hungary to the broader legacy shared by all of Europe and all Indo-European peoples.