An introduction to the greatest paradox in human rights

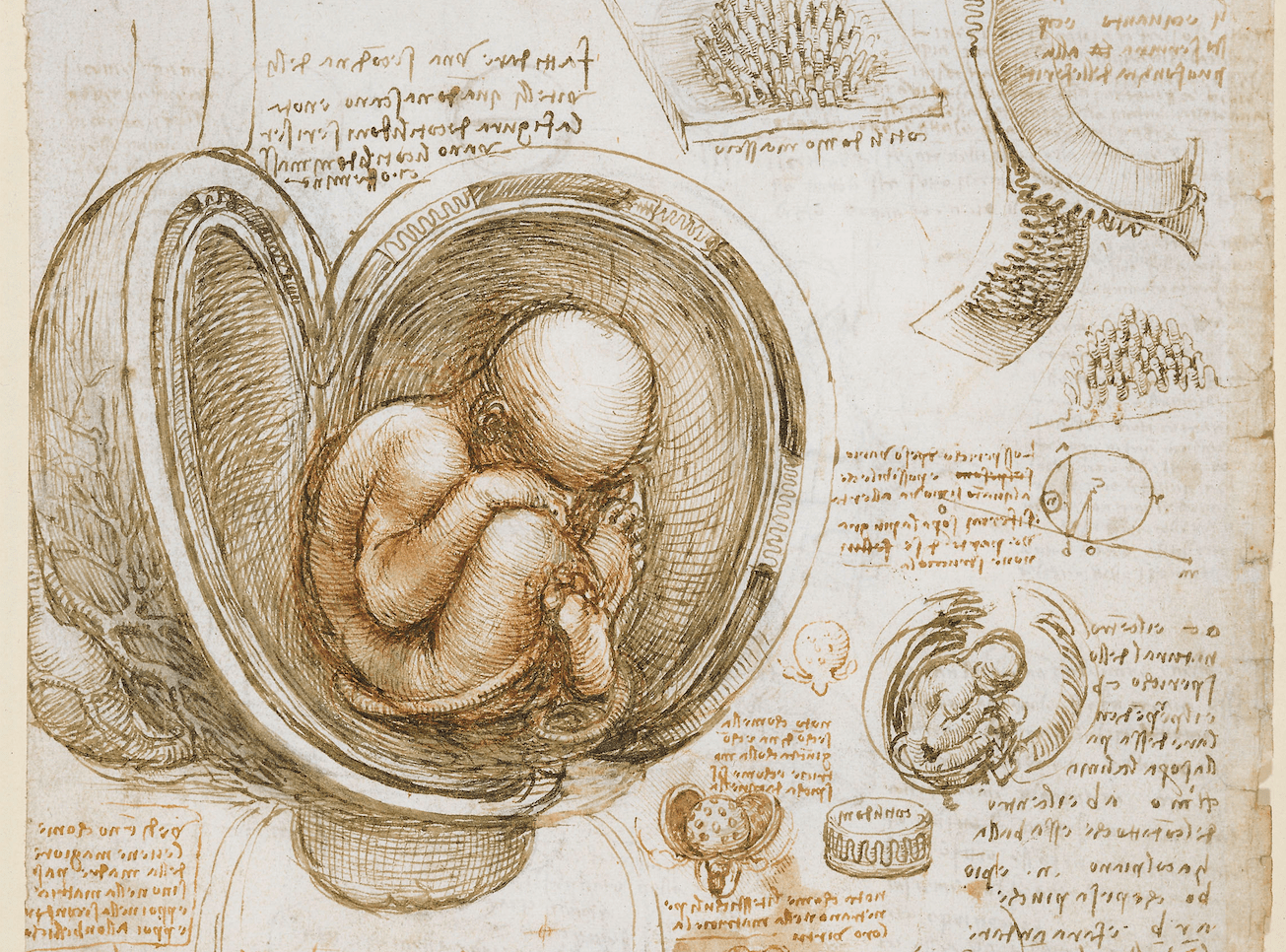

When one considers the aims of human rights activists, they usually state that they are fighting for everyone’s right to life and human dignity. In the past decades, a large number of minority groups (women, Blacks, homosexuals, etc.) were identified as victims of dominating majorities, to be protected by their newly established legal recognition. All these minorities have been receiving increased attention and protection through ever more complex and sophisticated laws based on the support provided by case law and international law, as well as open commitments and direct communication generated by international bodies and NGOs. However, the case of living human foetuses has not been settled or even addressed at all. Why? Well, as I will try to demonstrate later, human foetuses, that is, humans who have yet to be born, are in fact the least valued beings in our societies. As Ronald Reagan once put it, ‘I’ve noticed that everyone who is for abortion has already been born’.

First, when looking at the growing understanding of inalienable rights to life and human dignity, we see that even serial killers’ lives must be spared and saved from capital punishment in accordance with the general conception of human rights and international law. As for people with intellectual disabilities, the last human-rights-related United Nations Convention, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD), clearly states that ‘States Parties reaffirm that every human being has the inherent right to life and shall take all necessary measures to ensure its effective enjoyment by persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others’.1

In this paper we will focus on the different legal arguments for and against the right to life in the context of the relevant international laws, covenants, and legal texts. My aim is to provide some more arguments, as well as to express my opinion, which dissents from mainstream thinking as regards the need for a unified and unambiguous standpoint without any exceptions, in terms of universal human rights for all human beings. For the record, I do not wish to present the religious points of view or moral arguments used in the debate by pro-life supporters.

1. Right to dignity and life in international law, and what it lacks: clarity

There is a common agreement in legal literature that the first, and most important, international charter on human rights which expressly stated the rights to life and human dignity is the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. One important point often overlooked by scholars is that Articles 1–7 of this text refer to human beings, and not to persons in general.2 Moreover, Articles 1 and 2 of the UN Declaration also prohibit discrimination based on age or other status.3 As the text states, the rights enshrined in the Declaration should be preserved and ensured ‘without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status’. Nevertheless, Article 5 of the Convention also declares that no one, regardless of legal capacity or any other circumstance, including age, can be treated in a cruel, inhuman, or degrading way.4

Interestingly, in Article 6, we encounter another term for the subject: everyone. It states that ‘everyone has the right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law’.

One may consider that this formulation follows from the disavowal of any form of discrimination as declared in Article 2. This, in fact, is in accordance with Article 16 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1975) as well as the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989). The latter also refers to human beings and not persons in Article 1: ‘For the purposes of the present Convention, a child means every human being below the age of eighteen years unless under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier.’ This notion can be found in the Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities, too, in Article 10 in particular, in which, as we have seen, ‘every human being has the inherent right to life and [State Parties] shall take all necessary measures to ensure its effective enjoyment by persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others’.

The only tenable conclusion is that everyone must inherently have a right to life, regardless of their age

We can find at least four different expressions for human beings as subjects under international law: ‘human beings’, ‘no one’, ‘everyone’, and ‘person’. Moreover, if we compare the aforementioned treaties with one another, the only tenable conclusion is that everyone must inherently have a right to life, regardless of their age. In addition to these expressions, perhaps when it comes to human beings there is a fifth, ‘invisible’ category in the field of inheritance law. In quite a few countries, including Hungary, if the father dies before the mother gives birth, the foetus is a legal inheritor, and can expect a share from the inheritance, meaning that it is not possible to finalize the inheritance procedure until the foetus is born alive. (If the foetus is killed and thus cannot inherit, the offender is only liable for more than serious bodily harm if he/she is not the mother.)

2. The pitiless war between pro-choice and pro-life

Even though the debate on abortion has been among the most heated topics during all US presidential elections since the 1970s,including the last election, little attention has been paid to this question from the point of view of human rights. Indeed, even among human rights activists, this appears to be a taboo topic. However, fewer issues could be more important, from the perspective of human rights, than the right to abortion, since the right to life is the oldest and most important of all human rights.

Let us see where we now stand in this heated debate. We may begin by recalling the famous pro-choice argument of Judith Jarvis Thompson.5 She established a model in which two people are connected to each other in order to preserve the life of one of them, a famous violinist. The other is a no-name person who is forced to save the artist’s life without his consent by connecting one of his organs to the body of the ‘parasite’ violinist. In Thompson’s model the foetus, like the violinist, plays the role of a ‘parasite’ connected to the mother. If abortion were forbidden, it would mean that the mother, who did not want to get pregnant, has to keep alive an alien body, like the no-name donor. But a foetus cannot be considered an ‘alien body’ to its own mother, in contrast to the donor who indeed has no link to the violinist. While we can agree with the model of Thompson in terms of the right to the personal and exceptional control of one’s own body, pregnancy presents a completely different case. Furthermore, even when the parents in question do not plan to have a family or intend to keep the baby, pregnancy—except, for example, IVF in which parents are also obliged to sign their free and mutual consent on pregnancy (here: in-vitro procedure) beforehand, like a civil contract— is the result of sexual intercourse based on mutual agreement and enjoyment. Thus, the two parties should bear in mind all possible consequences and outcomes, including pregnancy, when having sex. So, referring to Thompson’s model, the connection between mother and child (together with father) could be considered a kind of special civil contract.

3. The American road to the unknown: from the legalization of abortion to the new notion of unborn victims?

As can be observed, in the US a pitiless war has been raging between so-called pro-choice and pro-life groups and activists. Some who support the pro-life position have even committed terrible crimes, including murdering doctors who practiced at abortion clinics created after the landmark 1973 decision, Roe v. Wade, of the US Supreme Court.6 Perhaps the biggest turnaround—though without any real consequences—was reported in the case of American gynecologist Bernard N. Nathanson (1926–2011), who founded the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws (NARAL), a pro-abortion organization, in 1969, which played a significant role in the infamous Roe v. Wade Supreme Court case (1973). Nathanson also ran the largest abortion clinic in the United States until the mid-1970s, and nearly 75,000 abortions can be attributed to him. He later admitted that he had provided false information to influence the public and the Supreme Court.7 In addition, the story of the pseudonymous protagonist of the case itself, Norma McCorvey (1947–2017) is also extraordinary. When she became pregnant but did not want to keep her foetus because she was unemployed and depressed, on the advice of her friends, she lied that she had been raped by black men and, as there was only a very limited opportunity to abort her child, she—through her lawyers—sued the state of Texas. Although McCorvey used the pseudonym ‘Jane Roe’ during the proceedings, she was never personally heard during the case, and in the meantime, the child was born and abandoned. In 2004, after converting to evangelical Christianity, McCorvey filed a lawsuit in the Supreme Court to initiate a review, but it was rejected.8

Thirty years after the Supreme Court’s decision, a new act was adopted in 2003 under the George W. Bush administration, prohibiting the killing of foetuses by some extremely cruel methods (partial-birth abortion).9 This act by no means arrived out of the blue. Another act of legislation adopted one year earlier, the so-called Born-Alive Infants Protection Act assured legal protection to foetuses who managed to survive their own abortion.10 It stipulates that after being born (in terms of leaving and being separated from the mother’s womb) the living baby’s (foetus’s) life cannot be terminated, including cases of failed abortions. This legal victory was the result of several years’ effort in Congress because Democratic President Clinton had vetoed similar bills in 1995 and 1997. It is important to realize that the act itself focuses only on the methods of abortion, and not on the age of the foetuses. Until 2003, for example, even a six-month-old foetus could be legally terminated.

Although this law was contested by pro-choice groups referring to the Supreme Court’s aforementioned decision recognizing women’s right to control their own body and the fundamental right to privacy, the Supreme Court finally upheld the law, stating that the statute did not violate the Constitution.11 Even though the new law does not prohibit abortion, a new approach is likely to be developed regarding the right to life of foetuses. This time the Supreme Court was in accordance with American public opinion: an ABC poll in 2003 found that 62 per cent of respondents thought ‘partial-birth abortion’ should be illegal.12 One year later a new act was adopted in favour of the so-called ‘unborn victims’. This law states that a foetus can be seen as a legal person, and thus a potential victim of federal crimes. This means that it ultimately recognizes a child in utero as, a person, and as a victim, in cases where the foetus is subject to any of over 60 listed federal crimes of violence.13

4. Legislation in the EU – what is the EU institutions’ position on the subject?

As for the European Union, its institutions have no clear or unified stance on the question of the right of foetuses to life.

What is more, the European Commission ultimately determined that the EU has no competency whatsoever to regulate this issue. On 28 February 2014, the European Citizen Initiative ‘One of Us’ was submitted to the commission, gathering 1,896,852signatures. A public hearing on the initiative took place at the European Parliament on 10 April 2014.14 Several weeks later, on 28 May 2014, the European Commission adopted the Communication on the European Citizens’ Initiative ‘One of Us’.15 The EuropeanCommission, on behalf of the European Union, eventually—and perhaps justifiably— rejected the most successful proposal of the European Citizens’ Initiative. As for the reason given for declining ‘One of Us’, the European Commission stated that it had already decided on EU policies on the ethical rules and restrictions related to EU-funded research, which prevent the destruction of embryos.16

With regard to capital punishment, the European Council has adopted legal measures concerning human rights in the form of EU Guidelines since 1998

In order to understand the European version of human rights, which is very different from the US as regards capital punishment, we have to consider the paradoxes of the application as well as the argument for the abolition of capital punishment in Europe. With regard to capital punishment, the European Council has adopted legal measures concerning human rights in the form of EU Guidelines since 1998. The vice president of the European Commission, Catherine Ashton, indicated that the abolition of capital punishment worldwide was a ‘personal priority’ of her mission. Actually, this personal statement, made at the highest level, was the first EU Guideline of the Council on human rights in 1998. After the new member states joined the EU in 2004, the Council, the European Parliament, and the European Commission also expressed their commitment to abolish capital punishment through a joint declaration and by adopting a European Day against the Death Penalty in 2007. The Lisbon Treaty specified that member states must uphold the abolition of the death penalty. In addition, all member states ratified Protocol 13 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms17 on capital punishment.

The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, annexed to the Lisbon Treaty and therefore part of the EU law and the so-called acquis communautaire, is also very clear about the right to life (Article 2). It states that no one shall be condemned to death and no one can be executed. In addition, the next article (Article 3) moves on stating that everybody has the right to their own bodies (physical and mental integrity). The Charter also defends the rights of the involved persons when it comes to eugenics and organ transplantation. Consequently, in fact, we have at least three kinds of status regarding human beings; in Article 21 the EU clearly expresses that no discrimination is allowed on the basis of age, and therefore, of birth. It follows that this could pertain not only to the born living human beings, but to the living unborn human beings too.

Apart from the European Commission’s position, we should note that after 1988 the European Parliament (EP) took some crucial steps in the field of foetuses’ right to life, but legislation in this field lost momentum after 2000. The so-called Rothley Report18dealt with legal and ethical questions related to the right to life with respect to genetic engineering. However, it did not examine the issue of abortion, instead stating simply that the situation of human foetuses should be settled without any ambiguity (Point 29). Point 31 of the report states that even zygotes deserve legal defence, while guidelines, recommendations, and other forms of soft legislation are not sufficient to settle this critical issue. Furthermore, it recommends the prohibition of any method for maintaining the life of embryos in order to use their organs in medical interventions made for the sake of ‘the owner’ of the foetus or embryo.

At the same time, in another report, adopted under the name of the Casini Report,19 the EP also recommended that the number and time span of frozen embryos should be limited in the course of artificial conception. Seven years later, when the existence of a cloned sheep called Dolly was announced, ‘something’ changed and the British government adopted legislation that allowed human embryonic cloning for therapeutic reasons. Then in 2000, the EP adopted a new resolution on human cloning, Point A of which asserts that the value of human beings and human dignity should be among the most respected aims defined in the member states’ constitutions. The Fiori Report,20 which claimed the prohibition of embryonic cell research, was rejected. The Fiori Report also demanded that after successful artificial conception (insemination), the remaining living embryos should be adopted by foster parents instead of being terminated.21

5. Closing remarks

Even though most governments that ban abortion do not consider men to be responsible for the pregnancy, all of them allow fathers to ‘walk away’. This means that men are only responsible for the foetuses if the babies are born, or if men take part in IVF procedures as sperm donors. If a mother chooses to terminate her foetus because, for example, she considers it an unbearable burden to live with, she can find herself in a very difficult situation without any help or support. As the famous women’s rights activist Margaret Sanger once put it: ‘No woman can call herself free until she can choose consciously whether she will or will not be a mother.’22

However, by acknowledging this justifiable as well as inalienable right of all women, the basic question still remains whether this liberty is also due to women after sexual intercourse. Looking at an analogy taken from civil law, we may wonder whether we could indeed completely neglect different kinds of obligations before signing a contract or after it. Today, the holistic approach I have presented in this paper is still not the reality. I am also aware of the fact that human rights legislation has hardly been created overnight, nor will it be in the future. Without relying on demographic statistics, it is clear that before long we will surely experience the urgent need to have more babies, especially in the developed world. This need will be accompanied by new methodologies in education, based on the coming new intelligent technologies requiring adequately trained teachers. If we want to have a bright and sustainable future, we will need to defend the rights of unborn children in a world ageing faster than it ever has in history.

I sincerely believe that technology and science (robotics, automatization, smart solutions and services, etc.) will be able to respond to the societal challenges we are sure to face. I personally believe that the artificial womb,23 a technology still under development, will also modify the procedure of as well as the general attitude to abortion: instead of abortion, a medical operation will be provided in order to transfer the foetus to an artificial womb, and the unintended healthy babies will be offered for adoption to the growing number of infertile couples. And finally, for disabled babies, we will have many more new generations of prenatal medical treatment as well—but that is a different and hopefully a more promising topic for future discussion.

NOTES

1 Article 10.

2 Article 1: ‘All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.’Article 2: ‘Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty.’Article 3: ‘Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person.’Article 4: ‘No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms.’Article 5: ‘No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.’Article 6: ‘Everyone has the right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law.’Article 7: ‘All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination.’

3 See Article 2.

4 ‘No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment’ (Article 5).

5 Judith Jarvis Thompson, ‘A Defense of Abortion’, Philosophy & Public Affairs, 1/1 (Fall 1971), http://spot. colorado.edu/~heathwoo/Phil160,Fall02/thomson.htm.

6 Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973). Full text: https:// supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/410/113/case.html.

7 ‘How many deaths were we talking about when abortion was illegal? In NARAL (National Association for Repeal of Abortion Laws) we generally emphasized the drama of the individual case, not the mass statistics, but when we spoke of the latter it was always 5,000 to 10,000 a year. I confess that I knew the figures were totally false, but in the “morality” of our revolution, it was a useful figure, widely accepted, so why go out of our way to correct it with honest statistics?’ The official figures of maternal death due to illegal abortion before abortion was legalized was 160. Dr Nathanson estimates the actual figure to be around 500 maternal deaths per year. (Bernard N. Nathanson, and Richard N. Ostling, Aborting America (New York: Pinnacle Books. 1979, 193.)

8 See https://edition.cnn.com/2004/LAW/09/14/ roe.v.wade/.

9 The Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 2003 (Pub. L. 108–105, 117 Stat. 1201, enacted November 5, 2003, 18 U.S.C. § 1531,[1] PBA Ban).

10 http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-107publ207/ html/PLAW-107publ207.html

11 Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124 (2007).

12 http://www.pollingreport.com/abortion.htm.

13 The Unborn Victims of Violence Act of 2004 (Public Law 108–212), http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW- 108publ212/html/PLAW-108publ212.htm.

14 https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press- room/20140407IPR42621/european-parliament-hearing-on-one-of-us-european-citizens-initiative.

15 https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/ en/press-room/20140407IPR42621/ european-parliament-hearing-on-one-of-us-european-citizens-initiativehttps://ec.europa. eu/transparency/documents-register/ detail?ref=COM(2014)355&lang=en.

16 https://www.democracy-international.org/eci-one- us-rejected.

17 The Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms also known as the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), of the Council of Europe adopted in 1950 to protect human rights and fundamental freedoms.

18 Report on the Ethical and Legal Problems of Genetic Engineering, A2-327/88, Official Journal C 96 (17 April 1989), 165–171.

19 Report on Artificial Insemination ‘in vivo’ and ‘in vitro’, A2 372/88, Official Journal C 96 (17 April 1989), 171–173.

20 Report on the Ethical, Legal, Economic, and Social Implications of Human Genetics, A5-0391/2001 (voted and rejected in plenary on 29 November 2001).

21 Articles 67 and 87.

22 Margaret Sanger, Woman and the New Race (New York: Eugenics Publishing Company, 1920), 94.

23 See https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/03/opinion/ sunday/abortion-technology-debate.html.