In the spring of 1848, or the ‘Springtime of Nations’, there were political upheavals throughout the whole of Europe. From Palermo to Berlin, from Paris to Bucharest, a series of revolutionary movements aimed to overthrow or reform monarchical government systems and create new nation states. The news of the French Revolution in February swept across the continent, which partly contributed to the outbreak of the revolutions in the cities of Vienna and Pest (it was still Pest and Buda before the unification of Budapest in 1873).

On 15 March 1848, two days after the events in Vienna, the radical youth of Pest, led by poet Sándor Petőfi, novel-writer Mór Jókai, and philosopher and historian Pál Vasvári, decided to announce their demands in the form of the ‘Twelve Points’ formulated by journalist József Irinyi. This was the beginning of Hungary’s one-and-a-half-year Revolution and War of Independence, during which the Hungarians fought so persistently that their resistance lasted the longest among all the European Revolutions of 1848, and in order to defeat it, the Habsburgs finally had to ask the Russian Tsar for help.

The Pilvax Café

The Revolution started in the Pilvax Café that once operated at today’s 7 Petőfi Sándor Street in Pest, as a favourite meeting point of radical intellectuals and the youth of the capital at the time. It was here that the The Young Hungary movement, with members like Sándor Petőfi, Mór Jókai, Pál Vasvári, and poets János Vajda and János Arany was founded, but the Tízek Társasága (Company of Ten) that included Petőfi and Arany, among others, also operated in the café. According to Petőfi’s diary, the plan for the revolution was born in the Pilvax Café, suggested by the intellectuals of the ‘March Youth’, and he apparently recited his poem ‘National Song’ for the first time here as well.

The building was eventually demolished due to urban planning, but in the 1920s, its successor, the Pilvax Coffee House & Restaurant opened its doors near the original location.

The Universities

The Youth of March first called upon the university students of the capital: on the rainy Wednesday of 15 March, Petőfi together with ten of his friends first went to the medical students of the Semmelweis University, and then to the students of the polytechnic and the law school at today’s Egyetem (University) Square. The proclamation and the Twelve Points were read aloud at all locations, and Petőfi recited the ‘National Song’, too. Led by Petőfi, together with the university students and the people of the street, the mass swelled up to around 2000 people.

The Press

The next stop of the crowd was via Szép Street to Kossuth Lajos Street, just a few minutes away, where the Landerer Publishing and Press Company operated between 1841 and 1852. Around 10 a.m., the crowd captured the Landerer & Heckenast Printing House in Hatvani Street, where they printed the Twelve Points and the ‘National Song’ without a censor’s permission. The first copies were thrown out the window to the crowd waiting in front of the building, and later they were distributed on the streets and in the garden of the National Museum. Seeing the enthusiasm of the crowd, Petőfi renamed Hatvani Street the ‘Street of the Free Press’.

The Twelve Points

The text of the Twelve Points of the Hungarian Revolutionaries of 1848 printed by the Landerer Publishing and Press Company read as follows:

‘What the Hungarian nation wants.

Let there be peace, liberty, and concord.

1. We demand the freedom of the press, the abolition of censorship.

2. Independent Hungarian government in Buda–Pest.

3. Annual national assembly in Pest.

4. Civil and religious equality before the law.

5. National army.

6. Universal and equal taxation.

7. The abolition of socage.

8. Juries and courts based on an equal legal representation.

9. A national bank.

10. The army must take an oath on the Constitution, send our soldiers home and take foreign soldiers away.

11. Setting free the political prisoners.

12. Union [with Transylvania].

Equality, liberty, brotherhood!’

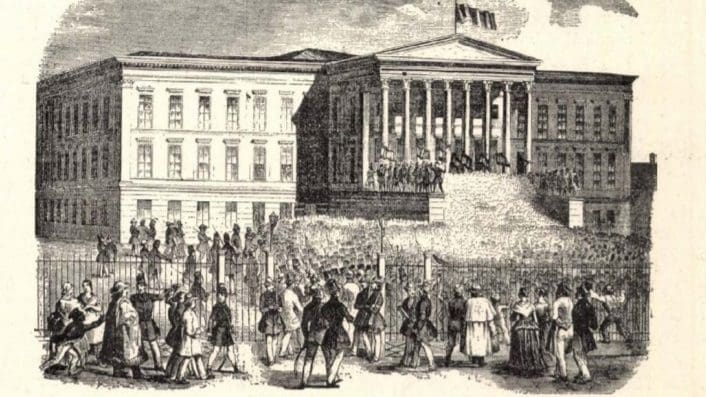

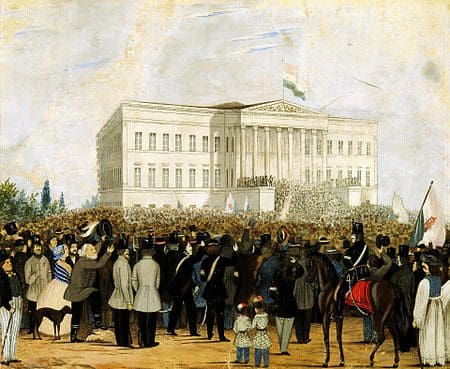

The National Museum

The next stop was also only a few minutes away from the Printing House: around 3 p.m., the crowd started to gather in the garden of the National Museum. There, in addition to Petőfi, Pál Vasvári and József Irinyi gave inspirational speeches as well, after which the mass accepted their proposals by acclamation.

The Town Hall

The fifth location of that gloomy day was at the former Town Hall, which was located behind the Inner City Parish Church in Pest. We can no longer see the church today, as it was in the way when the Elizabeth Bridge was built, thus it was demolished in 1900. The crowd gathering in the square next to the Town Hall handed over the Twelve Points to the councillors. The council members accepted and signed the revolutionists’ wishes, which Deputy Mayor Lipót Rottenbiller then presented through the window to the crowd waiting outside.

The Council of the Royal Governor

The crowd, which set off from Városháza Square and already swelled to nearly 20,000, continued to Buda to the Council of the Royal Governor, i.e. the highest governmental body of Hungary. Although the Chain Bridge had already been under construction, the crowd could not yet use it, so they crossed the gangway built next to today’s Vigadó Square instead and marched to the building of the Council at 53 Úri Street, where the country’s main administrative offices operated. Here, the Council of the Royal Governor accepted the demands of the revolutionaries.

The Release of Mihály Táncsics

Mihály Táncsics, Hungarian writer and political prisoner, was sitting in the nearby József Barracks for libel: after 1846, he demanded the liberation of serfs and distributed leaflets. The crowd marched to 9 Táncsics Mihály Street (later named after the prisoner Táncsics), released the writer, and took him to Pest in a carriage.

The National Theatre

The final venue of the events of 15 March 1848 was the National Theatre on the corner of today’s Rákóczi Road and Museum Boulevard, at Astoria (the edifice was demolished in 1914; today, there is an office building in its place). According to the original programme, on this day, the play titled Two Mothers and One Child would have been on stage, but due to the events, the management of the theatre decided to perform Hungarian playwright József Katona’s banned play Bánk bán (Bánk the Palatine) instead. However, the play was interrupted after a few scenes, and the majority of the audience wanted Táncsics to appear on the stage—however, indisposed, he spent the evening at the Nádor Inn instead.

Although Bánk bán was not continued that day, at the request of the audience, the crowd recited the ‘National Song’ together, then sang the Hungarian patriotic song ‘Szózat’ (‘Appeal’ in English), the Hungarian national anthem, the ‘Rákóczi March’, and some arias from the opera László Hunyadi, too.

The first day of the Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence of 1848–1849 ended in the National Theatre on the evening of 15 March 1848, with the interrupted performance of Bánk bán and the subsequent celebration of the crowd. Only after the one-day bloodless revolution in Pest and Buda did the real Revolution begin: the next day, on 16 March, Sub-lieutenant of Pest County Pál Nyáry and Deputy Mayor Lipót Rottenbiller took the lead of the movement, which thus really became of national importance.

Click here to read the original article