The following is an adapted version of an article written by Emese Hulej, originally published in Magyar Krónika.

In its series about Hungarikums, Magyar Krónika presents, among others, the trade secrets of the treasures of the Collection of Hungarian Values—this time, one of the most famous ‘Martian’ scientists John von Neumann’s oeuvre.

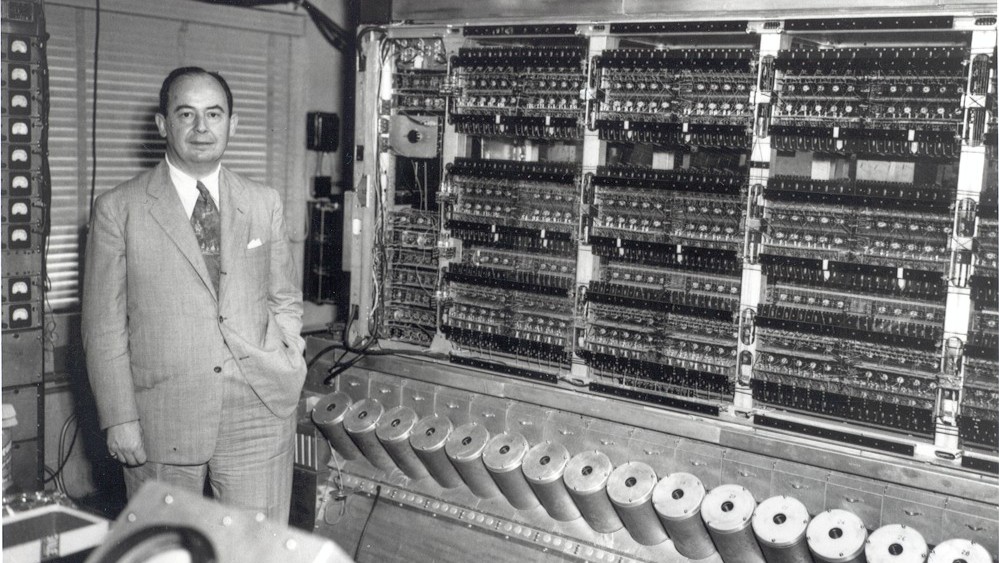

Smartphones, computers, weather and stock market forecasts, moon rovers, space probes, nuclear weapons, artificial intelligence. Behind them all lies the same name: John von Neumann. The genius whose mind worked faster than anyone’s and who could deduce the most important thing: the direction the future would take. He was a prophet—with a strictly scientific basis and tools.

This round-faced, eccentric oddball, who even sat on the back of a mule in a three-piece grey suit, had already anticipated the climate crisis in 1955 because he was not only quick in his thinking, but he could also make an unerring judgement about which of the factors would be more significant. This is perhaps the most important part of John von Neumann’s oeuvre, listed now as a Hungarikum: that he invented the future. He knew everything—is it the future he wouldn’t know?!

The man, who died painfully young at the age of just under 54, was a sophisticated speaker of his mother tongue all his life. He was born in Budapest in 1903, a few days after Christmas. He was brought up in a very wealthy family, with educated, loving parents. Miksa Róth, a famous glass artist of the time, made an image for the Neumanns’ home, in which three animals—a rooster, a rabbit, and a kitten—represented the three boys of the family, Jancsi (that is, John, depicted by the rooster), Misi, and Miklós.

It became clear early on that the eldest Neumann boy was a child prodigy. On the one hand, he could talk to his father in ancient Greek at the age of just eight, and on the other, he was capable of doing mathematical operations with eight-digit numbers—all in his head. At the age of nine, he posed the following problem to his parents: if God is omnipotent, is He able to create a stone so heavy that even He himself cannot lift it?

‘It became clear early on that the eldest Neumann boy was a child prodigy’

From one of the greatest schools of his time, the Budapest-Fasori Lutheran Secondary School, under the hands of legendary teacher Mr Rátz, he went to three universities in parallel. He wanted to be a mathematician, but the family persuaded him to study chemistry as well so that he would have a more useful degree in his hands. This is how he graduated in Budapest, Berlin, and Zurich at the same time. He also taught at the University of Berlin, becoming the youngest private tutor at the age of just 24. The young man, who worked together with Albert Einstein, Max Planck, Erwin Schrödinger, Edward (Ede) Teller, Leo Szilard, and Eugene (Jenő) Wigner in the German capital, went to cabarets and nightclubs in the evenings. But more than anything else in the world, he particularly liked to think. He himself found pleasure in the unimaginable power of his own brain. It was his passion.

He was a kind, slightly odd man who loved jokes and good company. He married twice; both his wives were Hungarian. His only daughter, Marina von Neumann Whitman, wrote an amusing book about him titled The Martian’s Daughter: A Memoir.

While still in Germany, he laid the foundations of quantum mechanics, a contribution to science on a scale comparable to that of Newton’s. In 1930 he moved to America and started to work at Princeton University, gathering the world’s greatest minds who went on to create the modern world. It was in this environment that it became common knowledge that Neumann was actually some kind of demigod masquerading as a human being for some reason. A Martian, a demigod, anything but this worldly being, who stands out from the rest. Neumann surpassed his contemporaries, too, in that he created worldwide work not just in one but in several fields. His game theory with Oskar Morgenstein won him many Nobel prizes, and he was also the central brain behind the Los Alamos programme, where Oppenheimer and his peers worked on the atomic bomb. He was the mathematician giving the physicist geniuses a method to calculate properly.

‘It became common knowledge that Neumann was actually some kind of demigod masquerading as a human being’

After the war he was also involved in the development of the hydrogen bomb, but by then he was already working on computers. He never patented his first computer—however, if he had worked for a big company, that company would never have had to worry about anything again.

Contemporary scientists, the military, and the world of politics all used his skills, his brain, in exactly the same way we use computers today. It was not without reason that Albert Szent-Györgyi declared Neumann to have had the most brilliant human mind ever.

The United States greatly appreciated and recognized him. He was awarded several consulting contracts and in January 1956 received the highest award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, from President Eisenhower. Sadly, when he arrived at the White House he had already been forced to be in a wheelchair. His shoulder pains, which had begun the previous year, quickly turned out to be bone cancer, metastases attacking his spine and then his most miraculous organ, his brain. His hospital bed was surrounded by military leaders so that even the smallest scrap of words could be taken away and used. From his death bed, he dictated at length to his scientist wife, Klári, quoting from Goethe, then took the last rites. Before his death, far ahead of his time, he was best interested in the relationship between the human brain and computers—what we know as artificial intelligence today.

This wonderful Hungarian mind, the most brilliant of Martian geniuses, did not live to see his 54th birthday. His untimely death may have been caused by his presence at the experimental detonation of the atomic bomb, at a nearby base, where, despite the prohibitions, his eternal curiosity as a scientist led him to remove his protective gloves when he went outside immediately after the detonation.

‘Albert Szent-Györgyi declared Neumann to have had the most brilliant human mind ever’

Last year a documentary film was made about his life’s work, The Most Brilliant Human Mind, directed by Lívia Bertha.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.