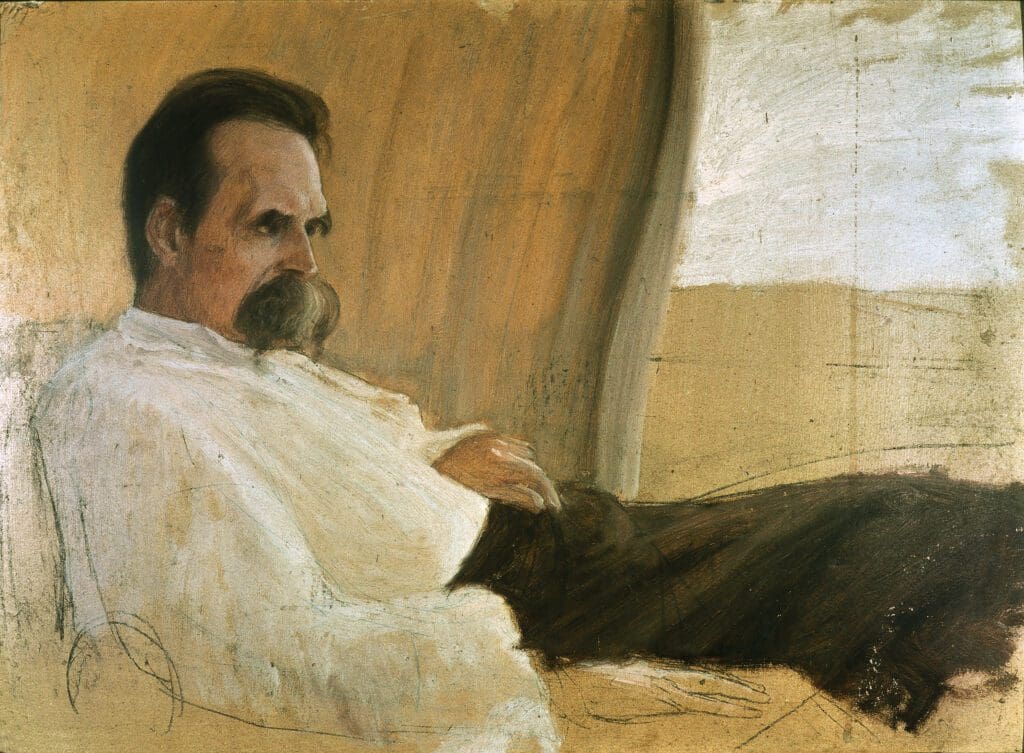

‘God is dead.’ These famous words, etched into the bedrock of Western culture by Nietzsche over a century ago, have been anathematised by Western conservatives even to the present day. Yet one might argue, even at the risk of inviting controversy, that he was not entirely wrong.

Nietzsche’s famous declaration about the death of God came in his 1882 work The Gay Science, which he described as the ‘most personal’ of all his books. At the time of writing, Nietzsche’s world had already been through the categorical social and cultural transformation that we now call ‘The Enlightenment’—a radical realignment in values, methods, and beliefs felt across the entire breadth of Western culture. This would ultimately transform the relationship between man and the state, the state and the sovereign, and the sovereign and man, spawning ideological bastard children such as communism and fascism, among others. God (and much, much more) was one of the first casualties of this transformation.

In the context of the post-Enlightenment landscape from which Nietzsche emerged, God is indeed dead

—as are myths and legends, angels and demons, and more. All of the things which made the world feel alive, or endowed it with magic and meaning, were bulldozed by Enlightenment rationality and positivism. In no sense was this Nietzsche’s fault; the groundwork on which he trod was set by Immanuel Kant over a century beforehand. Rather, by announcing the death of God, Nietzsche put into words a truth so terrible that few dared to speak it aloud: ‘God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers?’

Looking at the broader picture of the events from the Enlightenment until Nietzsche and well beyond, one cannot but imagine that God was in all likelihood only the first of many casualties resulting from the secular war on spirituality and superstition. Within a matter of decades, the sceptic crusade would even delegitimise the very idea of the Christian mode of being; that is to say, being in the world, but not of the world. The loss of confidence in the permanence of transcendent things (a loss felt among Christians and sceptics alike) created a graveyard of ideas that would be mourned by Nietzsche and his critics in equal measure.

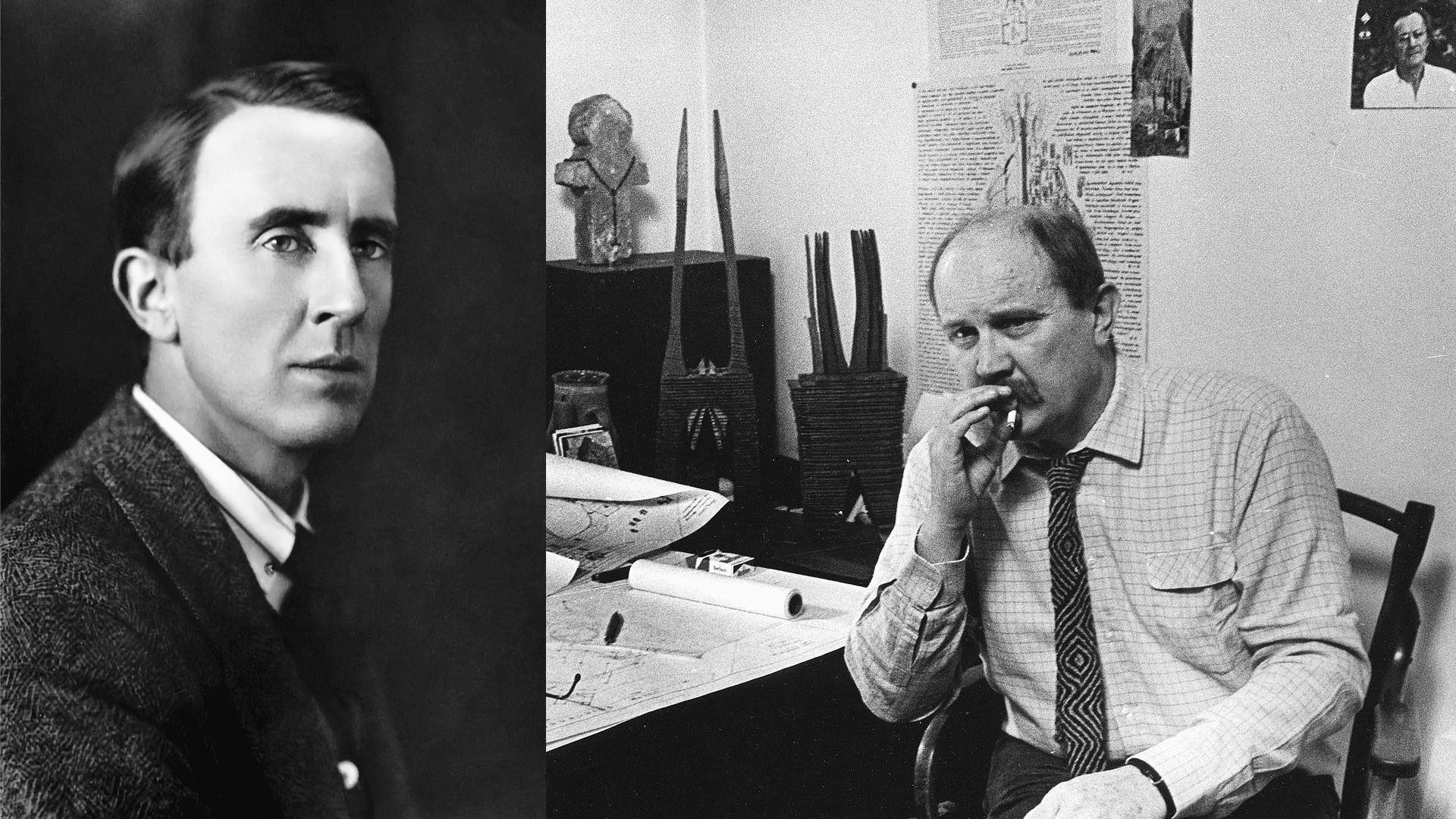

Later, authors such as J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, and Owen Barfield would attempt to resurrect the magic of the old world by inventing fantastical stories that sought to inspire readers with the mystery and majesty of what once was. In the early 1930s, they and other kindred spirits would coalesce into an informal literary group at Oxford University, calling themselves ‘The Inklings’. The Inklings and its members did not consciously consider themselves to be anti-Enlightenment activists, but their stories—The Lord of the Rings, The Chronicles of Narnia, The Silver Trumpet—de facto qualified for the genre. Their deliberate eschewment of literary modernity, in favour of thematic elements and settings drawn from Christianity and medieval Europe, firmly ensconced them as the torchbearers of a tradition that was at the precipice of annihilation by the time they had adopted it as the backbone for their writings.

But how was it possible for intellectuals so fully integrated into the establishment, such as Tolkien, Lewis, and Barfield, to become champions of a literary movement that rejected their modernity in favour of a nostalgic past?

The answer may lie in World War I: a genuinely traumatic moment in the history of Western culture, in which every wondrous invention or discovery that had been achieved in the wake of the Enlightenment was repurposed toward one brutally simplistic goal: killing.

Having served in the Great War, all three men (alongside other future authors such as Ernest Hemingway) came away from the experience with feelings of profound disillusion

and anomie toward the benefits of industrial modernity. The modern world, they realised, could just as easily build hospitals as it could produce gas grenades, flamethrowers, and artillery shells.

Tolkien was highly disturbed by what he witnessed in the Great War, and wrote at length in his personal notes and diaries about his feelings toward the war. In The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien’s post-war philosophy is expressed via antagonistic characters like Sauron (an originally angelic figure who began as a craftsman and smith) and Saruman, whose ‘mind of metal and wheels’ embodies the corrupt and anti-human industrial ideology that Tolkien so detested. At the same time, however, Tolkien drew inspiration from positive aspects of Western civilization, as well as the negative. The Anglo-Saxon burial mound unearthed at Sutton Hoo in 1939 by amateur architect Basil Brown (subsequently played by Ralph Fiennes in the 2021 hit film ‘The Dig’) had a massive influence on Tolkien as a lifelong medievalist and scholar of Anglo-Saxon history. Many elements unearthed from Sutton Hoo later made their way into Tolkien’s work, influencing the development of his fictional Rohirric civilization both aesthetically and culturally.

In Hungary, where mythologised memories of Árpád the Conqueror and István the Saint still play a role on the cultural stage,

there were other figures who stood alongside Tolkien and Lewis in rebellion against the oppressive monotony of Enlightenment thought, and the ruthless rationalism which accompanied it. Among the most important of these was a man named Imre Makovecz, an architect who devoted his life to the advancement of quasi-traditional architectural styles that emphasized pre-modern spirituality and the inherent magic of the natural world.

Makovecz was born in Budapest in 1935, and died there in 2011. After graduating as an architect, he spent his life pursuing the development of a style of architecture that could harmonise the pre-Enlightenment spirit with the postmodern zeitgeist of Communist-era Hungary. To understand Makovecz’s work, and what he set himself against as an architect, it is crucial to understand that he never attempted to merely ‘recreate’ the past of magic and myth. Makovecz fully understood that the past, being the past, could never be authentically brought back to life. Rather, he sought to take the stories of his childhood (of Hungarian folklore and fairytale) and to draw from those an architectural aesthetic that could reinforce the magic of pre-Enlightenment times, thereby bringing back to life the magic and wonderment of the ‘Old Hungary’ through the medium of buildings that are used, lived in, and experienced.

Makovecz’s architectural style is considered to belong to the genre of ‘organic architecture’

—an approach which promotes harmony between human habitats and the natural world in which these habitats exist. Yet what is arguably particular to Makovecz is his near-paradoxical harmonisation of both anthropomorphic and Biblical themes in the design and construction of buildings —almost irrespective of their intended function. Every building Makovecz produced was, in one way or another, magical. Despite the burdensome demands for building permits demanded by the communist bureaucracy, the magical essence of his work never changed.

The spirit that animated Imre Makovecz, and manifested itself in his work, produced architectural results that resembled helmeted warriors, or the wings of angels, or other themes derived from Transylvanian folklore. What he sought to do in his work was not to simply recreate a simulacrum of the pre-Enlightenment world—far from it, in fact. Instead, he wanted to create habitable works of art that could reinstill the feelings of confusion, admiration, and wonderment that were ubiquitous in pre-modern times.

J.R.R. Tolkien was an author, and Imre Makovecz was an architect. But while they may be divided by their crafts,

the two men were, I argue, united in spirit.

Both Tolkien and Makovecz saw in the modern world that something had gone awry; that something had been lost. Both figures knew that they could not resurrect the dead, or bring the long-lost past back to life, but they could reimagine it in a way particular to them and the unique talents they possessed.

Perhaps most importantly, Imre Makovecz and J.R.R. Tolkien both shared a conscious awareness of being born into a world forever scarred by the Enlightenment, where rationalism had decisively triumphed over religion, and where Nietzsche’s ‘death of God’ was considered a fact of life, rather than an academic theory. Yet both defied the cynicism and atheism of their surroundings by spending their entire careers crafting worlds of imagination that could offer an alternative to the post-Enlightenment world they had inherited.

They did so at great personal risk, defying the norms and aesthetic preferences of their contemporary societies to fight their crusade, and as such we are obligated to respect and remember them. These were the men who used their own imaginations to wage war against the death of God.

Related articles: