There is much talk of an impeding world war nowadays, and ironically enough, exactly 109 years ago, the same was true for much of Central Europe.[1] What historians refer to as the ‘July Crisis’ was technically a long series of steps toward military escalation which eventually culminated in the outbreak of World War I.

The crisis, of course, began already on 28 June 1914, when Gavrilo Princip, the Bosnian Serb nationalist activist assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife Sophie, during their visit to Sarajevo in Bosnia. Historian Cristopher Clark has referred to this process as ‘sleepwalking’, and indeed, many politicians at the time did not recognise the threat of a global war, with some even thinking that war was in their interest.

It was of course understandable that Austria-Hungary would seek some kind of revenge—after all, their heir to the throne had just been murdered. Serbia was seen as a major source of threat to the unity of the Austria–Hungary, therefore ‘dealing’ with this danger may have seemed logical. Serbia, however, was supported by Russia, and many foresaw that the ‘big bear’ would surely go to war if its ally was attacked. Austria–Hungary therefore turned to Germany for help, and Berlin, in turn, expected a quick declaration of war.

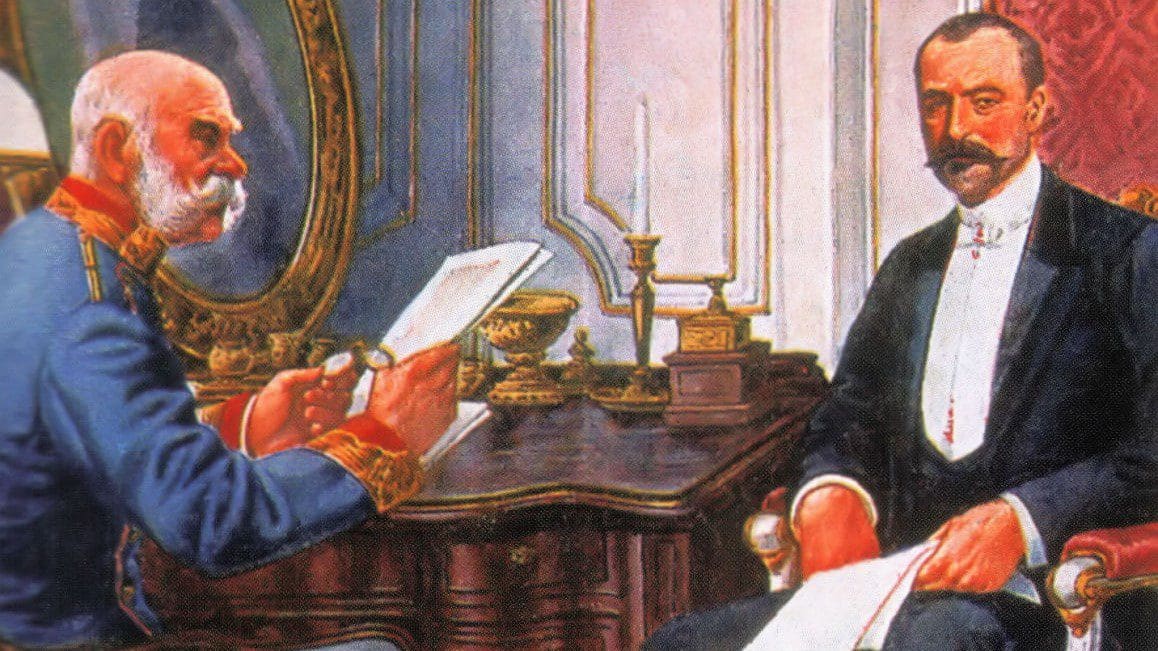

The Austro–Hungarian leadership deliberated the prospect of war. All Hungarians can take great pride in the fact that

the major opponent of the war was Hungarian Prime Minister István Tisza,

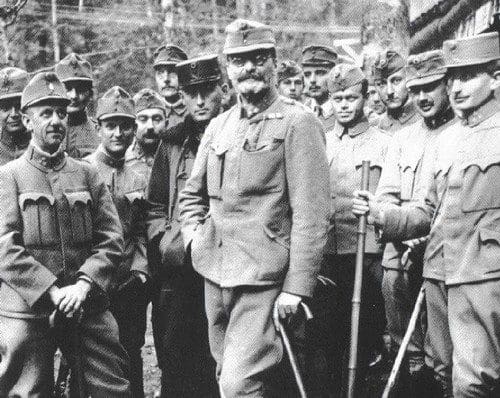

who foresaw that the conflict could escalate and lead to a ‘world war’. Despite his vocal concerns, Austria decided to give Serbia a harsh ultimatum on 23 July, but postponed any attacks until the full mobilisation of the Austro–Hungarian army to be completed by 25 July 1914. The Serbs rejected the ultimatum, and after the Austro–Hungarian army invaded, Russia, Germany, France and the United Kingdom also started mobilisation. By 4 August, all major sides had entered the war on the Old Continent.

Tisza’s views were perhaps characteristic of his wry and very much Hungarian and Protestant outlook. On the very day of the assassination, he travelled to Vienna, but not with the intention to contemplate war, but in order to win time for the Serbian government to dissociate itself from the murder. Tisza expressed hope that the international situation would improve and voiced his concern that in case of a war, Romania would surely stab Hungary in the back. Tisza decided to base his answer on the German position—which, however, was strongly supportive of going to war. Even after that became clear, Tisza still advocated for peace, and asked Vienna to wait until the results of the official investigation into the assassination arrive. But in the Council of Ministers a different view prevailed, and only one proposal of the Hungarian Prime Minister was accepted: namely, that Austro–Hungary would not ‘destroy’—meaning: annex—Serbia.

Had Tisza stopped at this point, surely his name would today be written in gold on the pages of Hungarian history books. Yet the Hungarian prime minister is mostly remembered for having been the head of government throughout the war years, and as the man who announced on 17 October 1918 in parliament that ‘we have lost this war’. Shortly afterwards, he was murdered, presumably by angry citizens, one of whom allegedly even blamed Tisza for turning his wife into a ‘whore’. (Meaning, probably, that because of the difficult war years, his wife was forced to look into other ways of making ends meet.)

Truth be told, by 14 July 1914, Tisza’s views had changed. After Serbia failed to meet the Austro–Hungarian demands, Tisza said that ‘it was difficult for me to support the war, but now I am firmly convinced that it is necessary, and I will defend the greatness of the Monarchy with all my might’. Of course, he might have had deeper motivations: he decided not to resign so as to not hurt Austro–Hungarian interests by signalling weakness.

Staying in his position could also help him advance Hungarian interests within the Monarchy.

Finally, mass opinion was—at least in the beginning—strongly pro-war: protests erupted in Budapest, where people carried banners reading ‘long live the war’.

Looking back at those fateful days, reading through the minutes of the meetings of major politicians deciding on the fate of Europe, it is hard not to see their narrow-mindedness, blindness, and naivety. They did not have sufficient imagination to fully fathom the devastation that the First World War would bring to the continent: the trenches, the countless dead, the tanks, the poison gas and the machine guns. Why did those who had the power to do so not pull in the reins? How could the civilised European populaces celebrate the war? Why did they not choose the path of peace, progress, and constructiveness? On the 109th anniversary of the start of the First World War, and in the shadow of the war of our time, these are the questions historians must answer.

[1] This article draws on the following sources: Christopher M. Clark, The sleepwalkers: how Europe went to war in 1914. Harper, New York, 2013.; Tibor Hajdu, Ferenc Pollmann, A régi Magyarország utolsó háborúja, 1914-1918, Osiris, Budapest, 2014.; Gábor Vermes Gábor, Tisza István, Századvég, Budapest, 1994.; Pál Hatos, Az elátkozott köztársaság, Jaffa, Budapest, 2018.