The origin of the Hungarian people has been a much debated issue throughout the country’s history. Various theories emerged over time, and the Hungarian national myth even incorporated narratives linking the Magyars to other steppe-roaming groups, such as the Huns and their half-mythical leader, Attila. However, in the 19th and 20th centuries, the scientific community reached a consensus that Hungarians most probably have Uralic origins. In linguistic terms, while there is a large corpus of ancient Turkish words in Hungarian, and Turkic tribes exerted a significant influence on Hungarian culture, the Hungarian language belongs to the Uralic group, making it related to Finnish, Estonian, and other languages in that family.

According to the subdivisions within the Uralic language family (also known as Finno-Ugric, if the Samoyedic languages are excluded) Hungarian is indeed related to the relatively widely-spoken Finnish and Estonian languages, even though the Hungarian language belongs to a different branch of the Uralic ‘tree’ than the aforementioned two. Rather than being part of the linguistic continuum of its Northern European kin on the Baltic shores,

Hungarian shares stronger linguistic connections with the distant Khanty and Mansi, living as far from Hungary as Western Siberia.

Uralic languages – Languages of the family

The two major branches of Uralic are themselves composed of numerous subgroupings of member languages on the basis of closeness of linguistic relationship. Finno-Ugric can first be divided into the most distantly related Ugric and Finnic (sometimes called Volga-Finnic) groups, which may have separated as long ago as five millennia.

Although Hungarians and the Khanty–Mansi ended up in completely different cultural, religious, and civilizational environments, exploring the Khanty and Mansi people can shed light on how proto-Hungarians and their lifestyle looked like. There have been extraordinary Hungarian scholars so enthusiastic about their distant cousins that they ventured to the edge of Siberia to collect invaluable data about them. Their work enormously contributed to what we know about these peoples. In fact, today almost every scientific work about the Khanty and the Mansi features references to Hungarian scholars.

Nowadays, the region with the largest population of Mansi and Khanty is the Khanty–Mansi Autonomous Area–Yugra in Russia, while some of the neighbouring administrative units in Russia also have considerable groups of these two peoples. The region today known as one of the most important territories for oil production in the Russian Federation has been under the control of the Rus’ principalities and then Russia since the beginning of the second millennium. The word Yugra (Югра) in the official title of the region refers its historic name and bears a linguistic connection to how Slavic languages designate Hungarians (from proto-Slavic ǫgъrinъ or ǫgrinŭ), as well as to the category of the Ugric languages. Whereas a more plausible hypothesis is that the European name for Hungarians is derived from the Onogur tribal alliance, according to some studies, it is possible that there is a linguistic connection between the word ‘Hungary’ and ‘Yugra’.

The linguistic connection that seems to be more likely is between the Hungarian endonym magyar and how the Mansi call themselves (мāньси). The Proto-Ugric word both nations derive their name from is mańćɜ, that simply mean man or person.

However, it needs to be noted that comparisons between Hungarian and these languages are compounded by the internal complexity of the latter—their dialects differ so much that the various Khanty and the Mansi groups have a hard time understanding each other.

Aside from common syntactic features, Hungarian and the Khanty and Mansi languages share lexical similarities as well.

For instance, a resemblance can be observed in the words fire (Hungarian tűz, Mansi таўт or taːwt, Khanty тут or tut), horse (ló, Mansi луў or luw, Khanty лав or law) or roof (Hungarian tető, Mansi такэм, Khanty тевтәм). Hungarian resembles possesses Mansi more, albeit an ancient connection with the Khanty is also evident.

In the video below, a Khanty girl is counting to six. It gives a native Hungarian chills to hear the child, living in distant Siberia, utter the number names, pronouncing them practically identically to present-day standard Hungarian.

Hanti lány számol ( Szurguti nyelvjárás)

Részlet az 1999-es az A Hanti sámán hagyatéka cimű filmből. #hanti #khanty #ugric #uralic #finnougric #finnugor #nyelvrokon #számolás

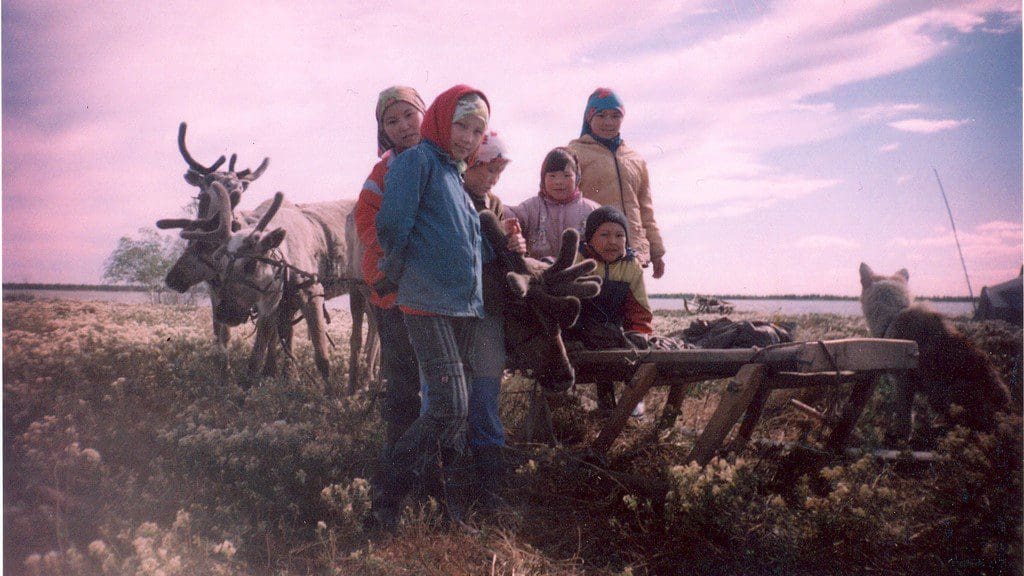

While upon closer examination the similarities between Hungarian and the Khanty and Mansi languages are noticeable, in terms of the overall way of life of these people the differences are enormous. Although a portion of the Khanty and Mansi populations, estimated at around 30,000 and 12,000 respectively, have embraced urbanization, many of these indigenous communities continue to uphold their traditional lifestyle. This way of life remains deeply rooted in nomadic and semi-nomadic practices, with their primary means of sustenance revolving around hunting, gathering, and engaging in deer herding activities.

The Khanty and the Mansi are included in the so-called ‘Indigenous small-numbered peoples of the North, Siberia and the Far East’ of Russia. This status gives them certain special rights regarding the preservation of their traditional lifestyle, for instance, special access to the utilization of natural resources of their homeland that they are heavily dependent upon. Those who follow a nomadic lifestyle traditionally reside in chums—a tent-like structure that shows resemblance to the Native American tipi.

Over the centuries, the Khanty and Mansi communities have maintained extensive contact with Russia, which resulted in a significant number of Russian speakers and followers of Orthodox Christianity settling among their populations. However, despite Russia’s and Christianity’s influence, many individuals within these communities continue to embrace their old shamanistic beliefs. Interestingly, however, there also exists a blend of Christian and pagan beliefs that is followed by some Khanty and Mansi. Similar blends are also common among various other peoples in Russia due to their relatively late exposure to Christianity.

Prominent Hungarians have greatly contributed to the scientific study of the Ugric peoples as well as to Uralic studies in general.

One of the most important contributors to the field was Antal Reguly (1819–1858), an ethnographic researcher and traveller, who, after venturing into the northern Urals and exploring it in enormous detail, learnt the Khanty language and studied the people. At the request of the Russian Geographical Society, Antal Reguly compiled a geographical and ethnographic map of the northern part of the Urals. In addition to the forests, fields, rivers, and roads, the map showed settlements, drew ethnic borders of the peoples of the region, and also indicated the route Reguly had travelled with his detailed notes. Later, one of the peaks of the Urals was named after Reguly, which perpetuates the name and accomplishments of the Hungarian scientist and more broadly, is a symbolic salute to the contribution of all the Hungarians who explored the region.