Ever since the creation of the Hungarian state, the question of Hungarians’ origins had been of interest as it is important for the creation of a national identity. The search for Hungarians’ origins was connected to the unknown location of the original, ancestral homeland of Hungarians. Unfortunately, there are no remaining written sources on the Hungarian side about where they came from—the lack of sources left questions about the identity, past, and the characteristics of the ancient homeland unanswered for many centuries. The sources of the neighbouring Rus or Byzantium, as well as the Arabs, who were among the first to report on the arriving Hungarians, did not suggest any explicit new information on the matter either.

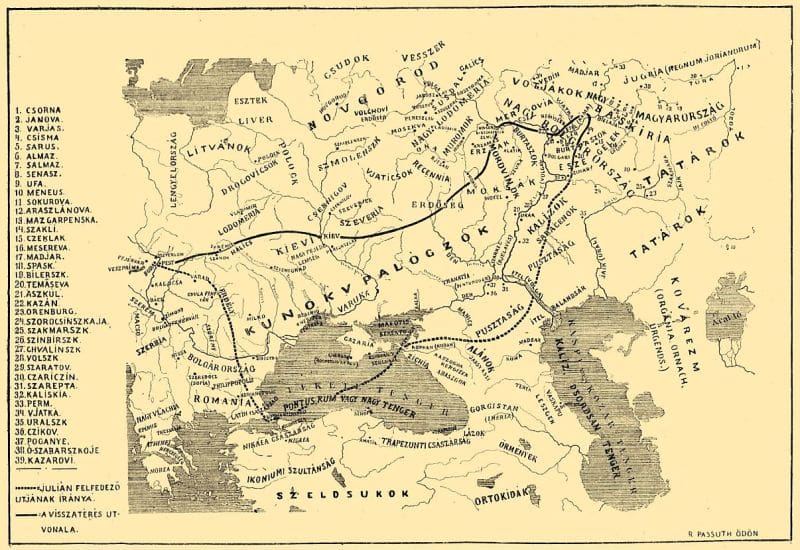

Among those whose minds were tormented by the issue of the Hungarian Homeland was the Dominican monk Friar Julian, who journeyed to the East in the 13th century, where he found a branch of Hungarians who supposedly remained nomadic and pagan.

The motivation behind Friar Julian’s journey to find the homeland of the Hungarians, referred to as Magna Hungaria in the sources, extended beyond a romantic yearning to reconnect with his Eastern kin. It was imbued with profound religious sentiments as well,

as one of the goals was the conversion of the ‘Eastern Hungarians’. After completing his travel through the Black Sea and the Pontic-Caspian steppe, Julian supposedly did find the Eastern Hungarians—later, his experiences with the Hungarians were recorded by his friend, monk Richardus:

‘They have no idea about God, but they do not worship idols either, abd they live like wild animals. They do not cultivate the land, they eat horses, wolves and meat of that sort, horse milk, and they drink blood. They abound in horses and weapons and are very valiant in warfare. They know from the traditions of the ancients that those Hungarians came from them, but they did not know where they lived’.

Even though the venturers and the nomadic group of alleged Hungarians were separated by a couple of centuries of no contact, according to the historic records, Julian and the Eastern Hungarians could understand each other.

Upon returning home from Magna Hungaria through the Rus lands, Julian reported his experiences to King Béla IV. Julian then ventured on a second journey in 1237, however, it proved to be less successful than the first one. His second trip was hindered by the formidable Mongol threat, ultimately preventing him from entering the vast Eurasian steppe where he supposedly found Magna Hungaria a year earlier.

10 years later, Friar John of Pian de Carpine, who travelled to the court of the Khan of the Mongol Empire, also confirmed the presence of a ‘Great Hungary’ (i.e. Magna Hungaria) in the Volga-Uralic region. He named its dwellers ‘bascarts’—a word sounding similar to the name of modern Bashkirs inhabiting the area: ‘Comania hath to the north of it, immediately after Ruscia, the Morduins, the Bilers, or great Bulgaria, and the Bascarts, or Great Hungary’.

Even though the record of his travel is accepted by some historians, it appears that the legend of Julian’s discovery of Magna Hungaria is reminiscent of a half-myth, thereby, casting doubts about the accuracy of the documents of his journey.

Can the legend of the ancient Hungarian homeland that was discovered by Dominican monks be even plausible from a modern scientific perspective?

The short answer is actually yes, while the complete answer requires some elaboration.

Genetics research done in a collaboration of Hungarian, Ukrainian, and Russian scientists suggests that early Hungarians did come from the southern part of the Ural mountains. However, as the Kushnarenkovo–Karayakupovo culture of that area (that had a similar material culture to that of Hungarians’) had become extinct by the 13th century, Julian could not have found these people known to be associated with early Hungarians. As a result, Julian could not have ventured to the southern Urals and identified it as ‘Magna Hungaria’—he most likely called another region the ancestral homeland of Hungarians.

However, according to other research done in this field, in the 13th century, there still persisted a culture East of the Hungarian Kingdom that maintained a significant material connection to the early Hungarian migrants who settled in the Carpathian Basin. Moreover, a genetic link between the bearers of this culture and Hungarians has also been proven, implying these two groups have a common origin. This culture is known as the Chiyalik culture, that derived its name from the village of Chiyalek in Tatarstan. Due to its closer proximity to Europe compared to the other side of the Urals, the journey to this region from Hungary was not only feasible but also more plausible.

Based on the distinct characteristics observed in the excavated cultural layer, it is evident that the Chiyalik culture had a semi-nomadic lifestyle. The settlements they established were primarily used for seasonal habitation and were located in river valleys. Graves also indicated that the population adopted both Muslim and pagan traditions, which does not contradict the record left by Richardus about Julian’s findings during his travel. Later, this culture vanished as it underwent assimilation into Volga-Uralic Turkic peoples, Tatars and Bashkirs.

There are two important things to point out in light of this information. First, based on today’s research, it is indeed highly likely that Friar Julian found a group of people that spoke a language closer to Hungarian, and this people were related to the Hungarians who embarked on the journey to the Carpathian Basin centuries earlier. The material culture this group left is connected to that of the Hungarians, and the DNA research also shows a connection. Secondly, although the area where the Chiyalik culture was located is close to the current Hungarian homeland, recent archaeological and paleogenetic studies indicate that the territory Hungarians actually originated from is more likely to be even further away, to the East of the Urals. This implies that, although Julian did get close to the original territory, the Magna Hungaria Julian probably discovered is not the actual Hungarian homeland.

There are still mysteries to solve when it comes to Hungarian prehistory and paleogenetics.

Among the most important ones is the question of why Hungarians left their original homeland in the Urals and move further. Although Hungarians probably left later settlements behind due to the push and competition with different other nomadic peoples, there was no formidable steppe force near the 9th-century southern Ural region that could have potentially threatened the Hungarians. Moreover, although the settlements of early Hungarians were found in the Urals, they have been barely studied scientifically, and many questions as to how and why they were built still linger.

There is an especially curious connection between early Hungarians and the Bashkirs, the Turkic people that, together with Russians, inhabit the Hungarian Uralic homeland today. The seven Hungarian tribes who migrated to Transylvania and the Carpathian basin in the 9th century had similar names to the Bashkir tribes: Gyarmat – Jurmaty, Jenő – Jenej, Tarján – Tarkhan, Keszi – Kese.

Thankfully, the topic of Hungarian pre-history and paleogenetics is becoming increasingly popular these days, both in Hungary and in the countries where early Hungarians left their mark—mostly Russia, but also among Kazakh scholars, as the southern Ural homeland of Hungarians is partially located in their country. A recently published research paper in the renowned Nature journal is a great testament to the enthusiasm surrounding this topic. As both domestic and foreign researchers are becoming more and more interested in the issue, there is increasing hope that people like Friar Julian who care about their ancestors and the past of their people will shed light on the captivating history of the forebearers of Hungarians..

Related articles: