Freedom and love my creed!

These are the two I need.

For love, I’ll freely sacrifice

My earthly spell,

For freedom, I will sacrifice

My love as well.

Translation by Leslie A. Kery

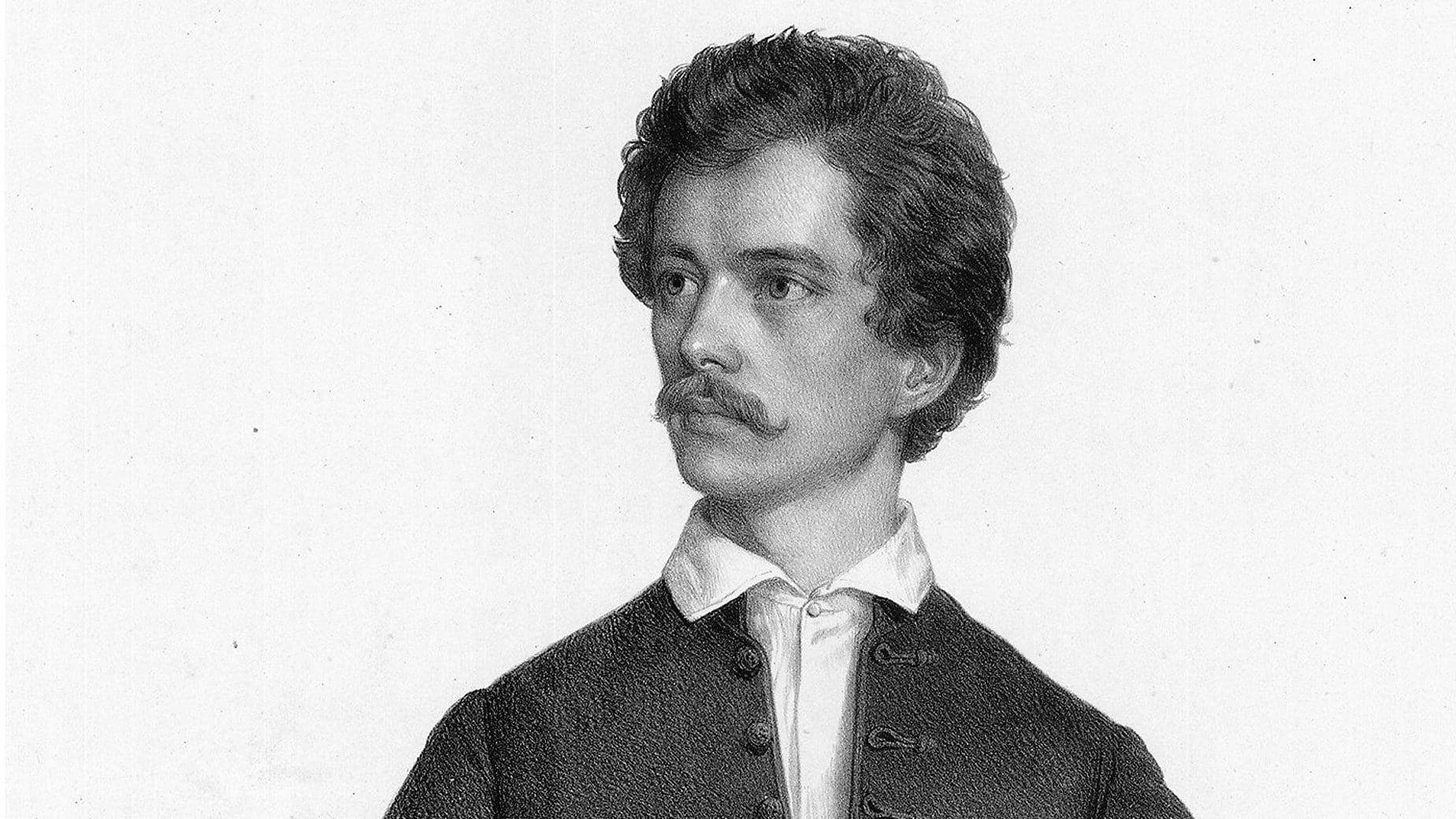

Sándor Petőfi was born 1 January, 1823, into a predominantly Slovakian-speaking Protestant family in Kiskőrös. His name at birth was Sándor Petrovics (or Alexander Petrovics as his Latin birth certificate testifies). In a very early age, he grew to be unsatisfied with his birth name. He experimented with multiple pseudonyms during his early career, but by around 1842 he settled for the name “Petőfi”. Petőfi is the loan translation of the Slavic name Petrovics. The name means, “son of Petrov”, and is equivalent to Petőfi, or Petőfi(a). The poet settled for the translation, “son of Pető”, instead of the more literate translation, “son of Péter”, because Vörösmarty (writer of the so-called “second Hungarian anthem”) named his protagonists Pető in his work called Eger.[1] Petőfi never legally changed his name, but from 1842 most of his poems were published under this name. From the Revolution of 1848 on his father, István Petrovics, also joined his son using the Petőfi name, but he did obtain official documentation legally certifying their names.[2]

Even as a young person Petőfi was dedicated to the arts. However, he was interested in acting and not in poetry. While in his early life his father’s business did provide him a stable financial background to study and by the time he enrolled in secondary education, his father went bankrupt. Lacking a stable financial support – despite parental and teacher disapproval – he tried to become an actor both to fulfil his passion and to ascertain an income. He briefly joined the military to escape poverty, but he was soon dismissed due to his poor physical condition. After years spent in poverty and struggling to get into theatres, his attention gradually turned towards poetry. Soon he achieved great successes and obtained the support of many contemporary and distinguished poets, such as Mihály Vörösmarty.

After years spent in poverty and struggling to get into theatres, his attention gradually turned towards poetry

Sándor Petőfi’s poems soon became known nationally for their romanticism and freedom loving patriotism. He was the first in Hungarian poetry to write about conjugal love and incorporate topographical poetry into his works, as in his poem dedicated to the Great Hungarian Plain. He has also written on the idea of freedom to all regardless of background more powerfully than anyone ever before in Hungarian literary history. His poems speak about opposing tyranny, worshipping freedom and in praise of the struggles for freedom that beset the Hungarian people. He was known for integrating the vernacular into his works, thereby emphasising the message of the poem over its form. Indeed his poems were a great source of inspiration for many Hungarians to join the fight for Hungarian independence during the Revolution and Freedom Fight of 1848-49.

True to his work, Petőfi died in the struggle for Hungary’s freedom

True to his work, Petőfi died in the struggle for Hungary’s freedom. Soon after the Revolutionary events of March 1848 turned into a freedom fight, he joined the army. While he briefly left the army to be with his wife during the later months of her pregnancy, he reunited with his unit under the leadership of József Bem – the Hungarian Freedom Fighters’ Polish General – as soon as he could. Petőfi was with the general on July 31, 1849, when Bem faced a Russian Imperial army triple the size of his. Despite Bem’s explicit prohibition, the young poet went to battle with a pen and a notebook to report about the events. Bem liked the young poet enormously so he did not permit him to engage in combat, but instead used him as his personal messenger and translator – Bem did not speak Hungarian. The poet was last seen around six o’clock that evening. Nothing certain is known about his fate after that time on 31st July, 1849, and he is believed to have been massacred by Cossack soldiers near the battlefield of Segesvár at Fehéregyháza (in today’s Romania). A couple of days before his disappearance in his last letter to his wife, he wrote full of hope about his desire to see his son utter his first words. Although in his life he has written around one thousand poems, only about 850 of them are known to have survived.

In the past year, the government has allocated 9 billion HUF to celebrate the 200th birthday of the Hungarian poet in 2023. The money has gone towards funding events, commemorating the bicentenary and developing museums, regional memorial houses and renovating memorials. According to the plans, events will be dedicated to Petőfi in over 200 locations all across the Carpathian Basin. There is a major movie under production about the events of the Revolution focusing on the role of Petőfi and his fellow radical young friends. The movie titled “Most vagy soha!”, or “Now or Never!”, focuses on the events of March 15th during the 24 hours of the Revolution Day which changed the course of Hungarian history. A series of artistic projects, book publications and even the production of a comic book about one of the poet’s work, The Apostle, was also financed by the government to mark the bicentenary of Hungary’s national poet, Sándor Petőfi.

The whole sea has revolted,

The nation in full spate

Has earth and heaven assaulted

And over sea-walls vaulted

With terror in its wake.See how she treads her measure?

You hear her, as she peels?

If you’ve not had the pleasure

Then watch her sons at leisure

Kicking up their heels.At nineteen to the dozen.

Great vessels roll about,

And fall where she has risen,

To hell with mainmast, mizzen,

And sails turned inside out.Pound on, exhaust your passion

Batter at passion’s drum,

Expose your depths, the riven

Furies and fling to heaven

The filthy tidal scum.Eternal heaven bear witness

Translation by George Szirtes

Before all heaven’s fools:

Though ships bob on the surface

And oceans run beneath us

It is the water rules.

[1] Szabolcs Osztovits, ‘Sors, nyiss nekem tért’, Osiris Kiadó (2022), 39.

[2]Osztovits, ‘Sors, nyiss nekem tért’, Osiris Kiadó (2022), 116.