If today, we think that medieval rulers lived their days in regal comfort, we are very much mistaken. If we look at the Carolingian manuscripts of the 8th and 9th centuries, we can find that kings were constantly on the move, accompanied by armed forces of varying sizes, and there was hardly a year that they escaped without an armed confrontation. Thus, it is no coincidence that Charlemagne, King of the Franks, is said to have ruled his empire from the saddle for 46 years. All this was not without dangers at all, as kings were not spared death, captivity, or epidemic disease either. Suffice it to mention the sad fates of Harold II of England (d. 1066), Ottokar II of Bohemia (d. 1278), and Richard III of England (d. 1485), who all died in battle, not to mention Richard the Lionheart (d. 1199).

Foreign authors usually tend to forget about the Hungarian monarchs who died in battle against the Ottomans, such as King Vladislaus I (d. 1444, known as Władysław III Warneńczyk in Bohemia) and King Louis II (d. 1526, known as Ludvík Jagellonský in Bohemia), although they fought on the same front as King Matthias I, or Matthias Corvinus, King of Hungary and Croatia. In the Middle Ages, Roman military expert Vegetius’ military manual was carefully read by rulers as well, but his words of caution were not much heeded. It was only the military writers of the 14th and 15th centuries, such as Christine de Pisan and Philip von Seldeneck, who categorically warned against the personal presence of princes in battles. King Sigismund of Hungary also played with fire twice, at the Battle of Nicapolis in 1396 and later at the siege of Golubac in 1428—he was just about an inch from being captured by the Turks.

We can also note that King Matthias (r. 1458–1490) spent many years of his reign in the saddle.

This was the case in 1463, 1467, and 1475, when he ‘celebrated’ Christmas in Jajce in Bosnia, in Brașov after the Battle of Baia, and then in Belgrade after the siege of the Szabács Castle. Naturally, if possible, Matthias also tried to celebrate great church holidays, such as Christmas, in a church of a settlement near his military camp, in the company of the high priests; and, according to the custom of the time, at a service lasting several hours, if he had the opportunity and his physical condition permitted.

The Ottomans took advantage of the turbulent years after Matthias’ accession to the throne to invade Serbia and Bosnia, which had been defending the country from the south.[1] King Matthias responded by launching an attack in the early autumn of 1463 to retake Jajce, the strongest fortress in northern Bosnia, and to restore Hungarian influence at the same time. It is a known fact that winter warfare has always been challenging, but Matthias thought that launching an attack at an unusual time of the year would surprise his opponents and deprive them of the opportunity to mobilize quickly. He was not disappointed eventually, but this allowed him to spend one of the most difficult Christmases of his life among his soldiers, among whom—at least according to the narrative of his historian Antonio Bonfini—he felt much more at home than among his courtiers.

The egg-shaped city of Jajce—hence its name (meaning ‘egg’ in Proto-Balto-Slavic)—was surrounded by rivers on both sides, and the castle was defended by a Turkish garrison of around 1,000 men for three months, until Christmas Day. By the end of the first week of October, the Turks had abandoned the lower town and retreated to the almost impregnable citadel. In the harsh weather, it was no small task for the Hungarian army to surround and shoot at the fortress, to hold off the relieving Ottoman troops, and, last but not least, to supply their own troops. Just as the military events of the following year, the siege of Jajce was also put into verse in Latin by Janus Pannonius, the greatest poet of the Hungarian Renaissance and Bishop of Pécs. His words of complaint read as follows:

‘He was not hindered by the terrible hiss of the northern wind,

Nor the depressing chill of the bitterly cold winter.

At last, though, the agony and the running out of drinking water

overcame the rock-hard, fierce men.

And on that precious day when the Virgin brought salvation into the world,

The people of the castle surrendered.’*

Finally, on the news of the general attack, the Ottomans sued for unconditional peace. On 26 December they sent envoys to the Hungarian leaders, who celebrated the feast with a mass in the local Franciscan church. That night, the Hungarians marched into the castle, where many Muslims joined them, fearing reprisals from the Sultan. The King’s life may well have been in danger on several occasions during the siege, but the feat attributed to Stephen Gerendi of shooting a Turk who was lurking in wait for the King is probably just a piece of late fiction.

In contrast, before Christmas 1467, the fighting in Baia almost cost the King his life.[2]

In that year, Matthias wanted to punish his Moldavian vassal Stephen the Great (Ștefan cel Mare, r. 1457–1504), who had defied his authority. However, the Voivode skilfully avoided an open confrontation with Matthias’ army. By 15 December, the Hungarian King and his army had retreated behind the walls of Baia, where they thought they could rest from the fatigue of the winter campaign. However, they guessed it wrong, as they could only repulse the Romanians with great difficulty and at the cost of heavy bloodshed. Eventually, they broke out of the city successfully, routing the attackers, and hastily retreated to Hungary. The fact that King Matthias had to personally intervene in the battle while being seriously wounded himself, gives an idea of the magnitude of the danger.

There is still a debate among military historians today about who ultimately prevailed in the night battle, and the size of the forces that clashed. Matthias’ successful breakthrough at Baia is indisputable, even if his campaign failed.

Although the King’s humanists wrote of a glorious victory afterwards, it hardly corresponded with reality. It is certain, however, that both Voivode Stephen and King Matthias boasted of the battle flags they had captured from their opponents, some of which were placed on the walls of the Church of the Assumption in Buda. It was no coincidence, therefore, that the statue of Matthias erected in Cluj Napoca in 1902 was the most offensive to Romanian self-esteem, with its depiction of the captured Moldavian flag. In 1932, the brilliant historian Nicolae Iorga corrected the historical facts in his Romanian-language inscription on the statue: ‘Victorious in war, he was defeated by his own nation in Baia in his attempt to subjugate invincible Moldova.’ The wording and placement of this inscription have changed several times from 1940 to the present day, and it still continues to stir tempers.

According to the King’s court historian Antonio Bonfini, Matthias already celebrated that year’s Christmas in Brașov, which is hardly believable in the winter road conditions, as the King’s injury forced him to sit in a litter. The homecoming journey is thought to have taken through the Tulgheș Pass, which was a 230-kilometre (143 miles) route across the Carpathians, a distance that required a great deal of effort on the part of the wounded King’s entourage between 15 and 26 December.

The winter of 1475–1476 was also memorable for Matthias. Stephen the Great, Voivode of Moldavia, became an ally of the Hungarian King again after 1468, and

in January 1475, he defeated the Ottoman troops with Hungarian support at the Battle of Vaslui.

This allowed Matthias to avenge the Ottoman raids on Oradea in 1474, which had caused a nationwide outcry. This campaign aimed to capture the Turkish stronghold of Szabács, built five years earlier on the banks of the Sava River.[3]

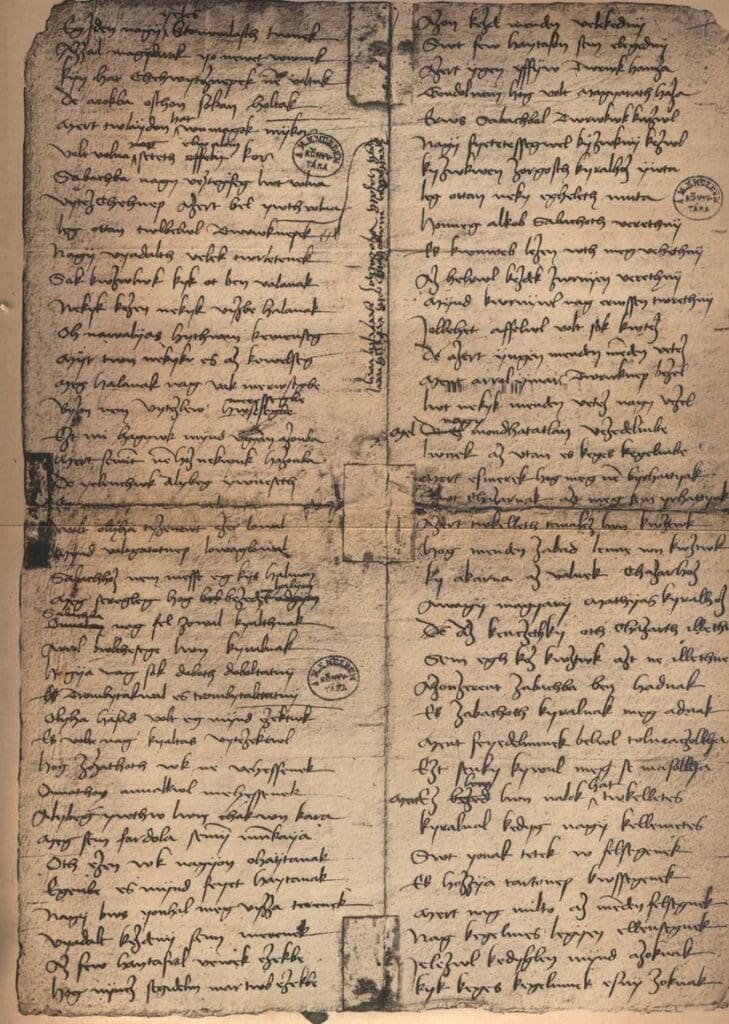

There are still conflicting opinions about the strength of the castle, but contemporary warriors considered it formidable, and it is no coincidence that the Hungarians spent 33 days besieging it. The difficulty of the siege is also attested to by the fact that the oldest surviving Hungarian historical song, 150 lines of which are now preserved in the National Széchényi Library, was written there. Earlier, the siege of Jajce in 1463 was also put into song, but only a two-line fragment of it has survived.

The sources reconstruct that on 18 November, Matthias’ ship joined the fleet going southbound on the Danube, heading towards Belgrade. The commanders of the army spent Christmas in the Belgrade Fortress, as evidenced by a letter written from there by Matthias on 30 December. The army had to carry a huge train because of the long winter months; the King had sheepskin coats made for his soldiers with Hungarian furriers in anticipation of the cold. In addition to war materials, the army took many other things with them as well, including 4,000 live geese and a large number of hens, as well as dried meat from 2,000 oxen.

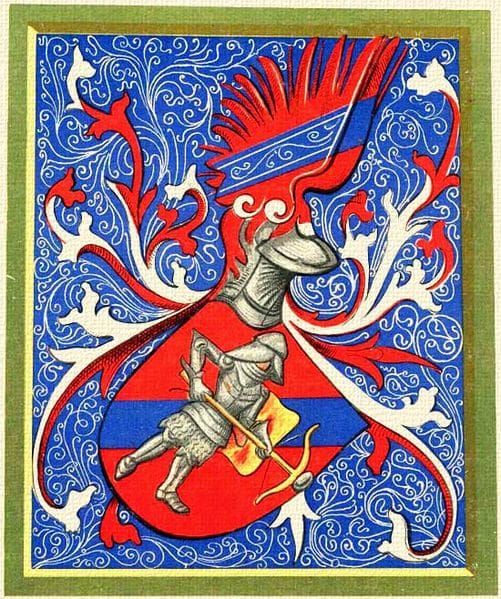

Although the besiegers successfully avoided a clash with the Sultan’s relief army, the Hungarian losses during the long siege were still significant. One of Matthias’ most distinguished Czech-born mercenary commanders, František Hag, also fell at the battle and was then buried with great honour in the Cathedral of Székesfehérvár.

It seems that the pursuit of danger was not alien to King Matthias’ personality.

A letter written to the Duke of Milan highlights the King’s exemplary courage at Szabács, as he was said to have stayed near the castle walls almost all along. It cannot be ruled out either that the story recorded by the chronicler Bonfini has some basis in reality, according to which the King set out in a small vessel in disguise to spy on the castle while being fired upon from above.

In 1476, after the successful siege, the Hungarian army tried to pacify the remaining Serbian territories north of the Danube and recapture the city of Szendrő, but to no avail. The King did not return to the scene of his successes later that year. He had more important things to do: he held his world-famous wedding in Buda with Beatrice of Aragon, daughter of the King of Naples, an event of splendour and astonishing wealth, the details of which have been recorded in various sources. It is no coincidence, therefore, that this is the most detailed Christmas we know about in the King’s lifetime, while only brief accounts of his life-threatening exploits in the military camps have survived. After all,

King Matthias deserved to celebrate his wedding on 22 December in the Church of the Assumption in Buda, far from the noise of battle, as well as to look forward to the possibility of starting a new dynasty based on his new marriage.

[1] Tamás Pálosfalvi, ‘The Political Background in Hungary of the Campaign of Jajce in 1463’, in Birin Ante (ed.), Stjepan Tomasevic (1461–1463) – slom srednjovjekovnoga Bosanskog Kraljevstva, Zagreb, 2013, pp. 79–88.

[2] Emanuel Constantin Antoche, ‘L’expédition du roi Mathias Corvin en Moldavie’, Revue Internationale d’Histoire Militaire, Vol. 86, 2003, pp. 133–165.

[3] Tamás Pálosfalvi, From Nicopolis to Mohács: A History of Ottoman–Hungarian Warfare, 1389–1526, Leiden, 2018, pp. 377–385.

* Translated by Hungarian Conservative.

Related articles: