Hungarian Zionist Max Nordau created the concept of ‘muscular Jewry’. In our article, we look at Nordau’s life, the image of the new Jewish man and the impact of the ideal in Israel.

Despite the fact that after Theodor Herzl–so well known in Israel that even Israeli premier Benjamin Netanyahu mentioned him during his visit to Budapest a few years ago–he is the second most famous Zionist born in Hungary, there are very few books or articles dealing with Max Nordau’s life. His last English-language biography was published by his own relatives in 1943, and the only Hungarian historian who has written about him is Hedvig Ujvári. However, as Herzl’s right-hand man, Nordau played a role not only in the organisational life of the Zionist movement, but also in laying the new spiritual foundations of the Jewish state by outlining the ideal of the new Hebrew (later Israeli) man and introducing the concept of Muskeljudentum.

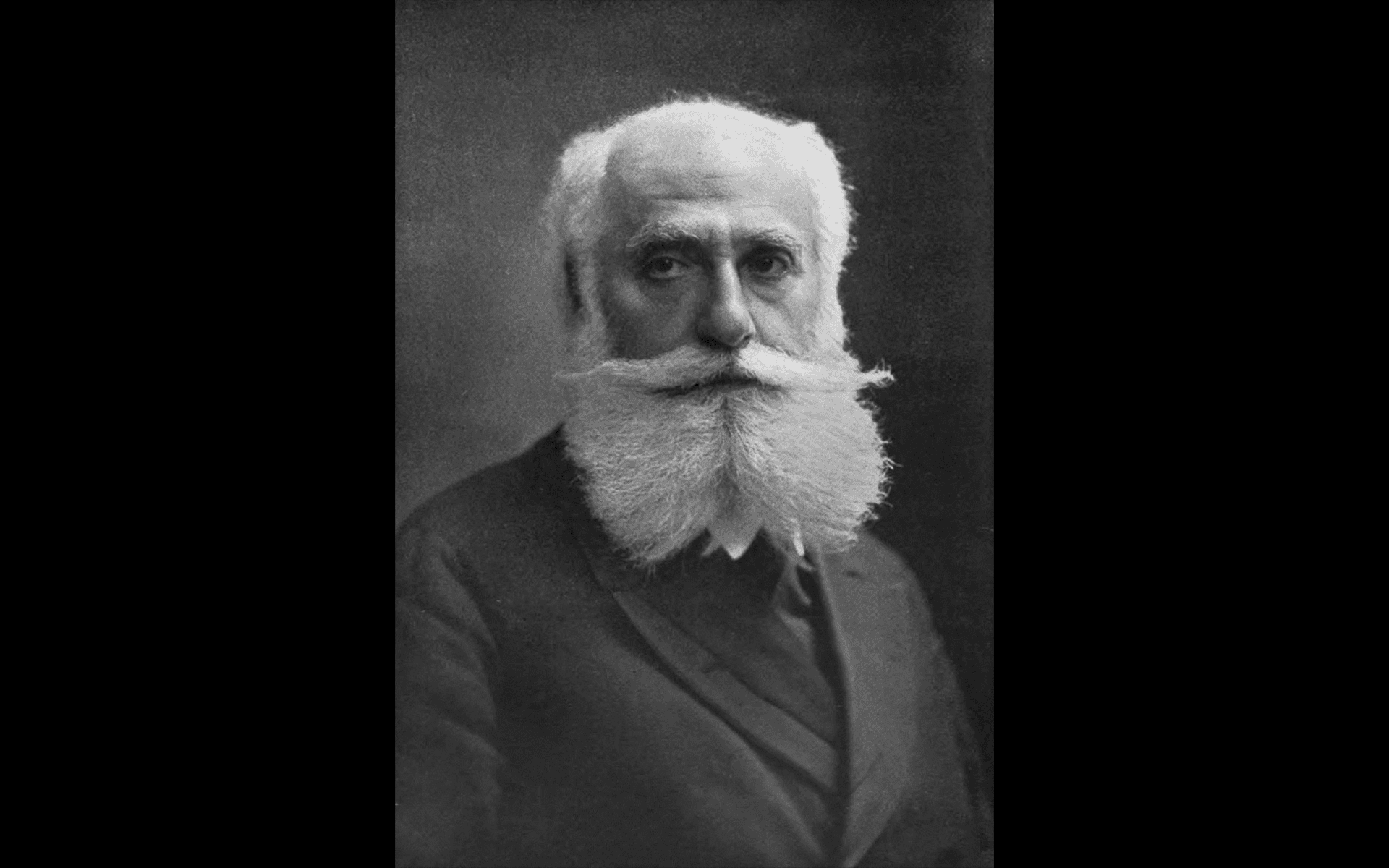

Max Nordau, born in Budapest as Miksa Simon Südfeld, was a doctor and publicist, whose early work not only covered numerous travelogues published in German, but also included internationally successful social science writings, such as The Comfortable Lies of the Cultural Life of Our Age and Degeneration. Nordau bashed ‘decadent’ art as a phenomenon that overstretched natural social structures, and The Comfortable Lies was so successful that even Hungarian Prime Minister Pál Teleki cited it in a speech supporting the numerus clausus law (a legislation in 1920 that barred most Jewish university students from education).[1]

All of this points to one of the interesting dualities of Nordau’s work: after taking up the cause of Zionism, while Nordau obviously worked for the welfare of Hungarian Jewry, and for the establishment of a Jewish state, he nevertheless found common ground with the nationalists of other nations, due to his nationalist and conservative views.

What led Teleki to quote Nordau, and what did Nordau think of some non-Jewish nationalist writers using his words to support their views? What did all of this have to do with Nordau’s views on society and on the improvement of Jewish society? And what do those now forgotten terms coined by Nordau some 120 years ago such as Muskeljudentum or Luftmensch actually mean? We shall attempt to answer these questions in our article, while presenting one of the least explored, controversial but intriguing chapters of the Zionist movement, and the Zionists of Hungarian origin who played a part in it.

The Zionist movement was a minority

Nordau’s writing about the ‘evils’ of Jewish society and their ‘correction’ must be interpreted in the context of the nationalist discourses of the time. As Walter Laqueur, a noted scholar of the history of Zionism, noted in his grand monograph on the movement, some Zionist essays with a nationalist tone can seem sinister in the decades following the Holocaust, since most readers by this time are likely already armed against national feelings and particularisms. The texts must be seen in their context: the Zionist movement was a minority, opposed to the liberal mainstream, which had to deal with the elementary tasks of guiding assimilated Jews towards the Holy Land, and of demolishing competing fashionable and, according to them, utopian ideas before the turn of the century.

An excellent example of the above is the interview[2] that Nordau gave to the French anti-Semitic newspaper Libre Parole. The paper edited by Édouard Drumont, which played a major role in arousing the mood against Captain Alfred Dreyfus in France, requested–and was granted–an interview from Nordau in the winter of 1903. The conversation was recorded by the anti-Semitic writer Raphaël Marchand, and although this is not the only interview of this kind, bizarre to our eyes today–after all, one could read interviews with Jews in Nazi newspapers, just as Jewish newspapers sometimes interviewed anti-Semites–it is nevertheless interesting to see that two, theoretically, opposed persons exchanged views.

The initial description of Nordau was given by the author in a tone balanced between hostility and respect: ‘A short man is standing in front of me, rather stocky – that is, typically Jewish. A long, snow-white, combed beard frames his face. He has curly and snow-white hair around his bald head. Two very vivid black eyes light up his face – a patriarchal face with a pointed chin, such as could be found in the Book of Judges and the pages of the Book of Kings.’

Nordau had a conversation with the anti-Semitic journalist in a similar tone. As he said, he now opened his door to an ‘adversary’ – i.e. he did not harbor illusions about the extent to which it is possible to cooperate with self-declared Jew-haters. In his words, however, he referred to a common national vision, and he himself clarified that he believes in the ‘racial’ nature of Judaism, which was a then fashionable, now unpleasant, expression of certain objective factors arising from origin.

‘I am a nationalist myself, but a Jewish nationalist. When a race has a character as distinctive, as recognizable as mine, it cannot and need not blend in with other peoples. It must become a nation again. There is no question of religion here, only of race, and there is no man with whom I agree more on this point than Meussieur Drumont himself. Meussieur Drumont, a French nationalist, says: France belongs to the French! And my nationalism shouts: Palestine belongs to the Jews!’

So there is a Jewish author, Zionist politician, who at the same time believes in the Jewish race and considers non-Jews who repeat the same proposition to be his enemy. Before discussing the consequences that Nordau drew from his views on the nature of Judaism, it is worth answering the question of whether Nordau provided the defiant equivalent of the antisemitic race theory, a kind of ‘Jewish counterpoint’ ? The answer is clearly no: Nordau was one of the few Zionist politicians who had a non-Jewish wife, just as he was able to deviate from the general nationalist position on other issues.

For example, in the early Zionist dilemma of whether to establish a Jewish state in the Holy Land or whether to create a ‘temporary refuge’ for persecuted Jews in Africa, Nordau argued for the latter. (For this position, a radical Zionist activist tried to shoot him in 1903). However, in an interesting way, he represented the conservative position on the question of Jerusalem: while Chaim Weizmann, later the first president of Israel, saw Jerusalem as a kind of dusty, withered place, interesting only for religious Jews, Nordau repeatedly spoke in favor of the construction of the third Temple. However, one should not expect less contradictions from a radically innovative thinker like Nordau, who created two essential concepts of the image of the new Hebrew man: Luftmensch and Muskeljude.

*

If the name of Max Nordau is known by few people, even among those familiar with Hungarian Jewry, then the name of Rudolf Lothar, the Budapest-born Viennese Zionist essayist, is even less known. However, Lothar gave one of the most comprehensive justifications[3] in early Zionist literature for the nationalist self-criticism which Zionism regularly employed. Lothar argued that ‘there are two ways of raising children…One of the tools is disapproval, which aims to overcome the bad instincts of the little man, to punish his weaknesses and eradicate his lazy and bad tendencies. Another tool is praise. But [nature’s] reproach is destruction, and its praise is victory in the struggle for existence.’ According to his conviction, therefore, in the natural competition of nations, it was vital to identify the mistakes of Jewry on its own and to correct them with ruthless criticism.

And there was no shortage of criticism. Just as some authors in Hungarian nationalism–for example Endre Ady, Ottokár Prohászka or Endre Bajcsy-Zsilinszky–criticized the Hungarian nation with strong words, so this form of self-flagellation was also fashionable among the Zionists. The Israeli historian Noah Efron wrote about this as follows: ‘One need not search hard to find denigrating images of the Altjude (that is, the old, non-Zionist Jew – ed.) in Zionist rhetoric and pamphletry.’ [4] The basic idea of many Zionist authors was that the Jews in the diaspora had become comfortable, weak, and incapable of the difficult life in Palestine. In fact, their use of words was so critical that Theodor Herzl once had to explain to British politicians that one can do ‘certain things’ to one’s ‘family’ , which others would take as an insult.[5]

This is how the propositions of Nordau, which he formulated at various Zionist congresses (1897, 1898, 1901) regarding the situation of the Jews, must be interpreted. These sessions were primarily internal discourses of constructive criticism: just as there are quarrels within a family, yet they present a unified image to the outside world, so in the Zionists’ perception, education by scolding had its place among the ranks of the Jews. This is what Nordau had in mind, when he said at the Fifth Zionist Congress that a very significant part of Eastern European Jewry was Luftmensch, i.e. ‘air man’: this term simultaneously referred to the unstable economic situation and cultural non-embeddedness. He laid out his thoughts in detail already at the First Zionist Congress: although the Jews of his time believed in liberalism, their non-Jewish neighbours did not take emancipation seriously, and therefore continued to limit their progress with prejudices. And this ‘pulls down the soul and destroys the body of the Jew’. This is how a situation could arise around the turn of the century, he argued, in which ‘the majority of Jews are a people of damned beggars’.[6]

He introduced the concept of ‘Muscular Jewry’

He presented a detailed panacea at the Second Zionist Congress, where he introduced the concept of ‘Muscular Jewry’, i.e. Muskeljudentum. Nordau believed that the only good answer to the deterioration of the physical condition in the diaspora could be the re-introduction of sports into Jewish life: ‘In the narrow streets of the Jewish ghettos, our poor limbs could not stretch; in our homes closed from the sun, our eyes blinked nervously…But the oppression is over. Now we have a physical space where we can live our lives…So let’s revive the ancient tradition of the warrior Maccabees, and let’s once again be men with muscular chests, strong arms, and steely eyes!’ [7]

The call was followed by the founding of numerous Zionist sports organizations, and a magazine called Jüdische Turn-Zeitung, i.e. Jewish Gymnastics-Newspaper, was launched. The magazine clarified that sports were good for combatting the ‘signs of degeneration’ and ‘an alarming increase in nervousness’ among Jews, and the editor of the paper, Hermann Jalowicz, stated that ‘Zionism is the healing serum against stale ghetto air.’ [8]

Of course, this did not mean that the Zionists were opposed to all the values of emancipation, but they undoubtedly saw certain dark sides of assimilation and cultural progress. ‘Emancipation was useful for the Jews…however, it disturbed the physiognomy of the Jewish soul.’ The paper therefore referred to sports in one place as ‘a defence organisation against intellectualism’. The editors of the paper would probably be surprised to note today the fact that the state of Israel is at the forefront of the world in the number of degrees per capita.

*

The common prickly pear is a sprawling, tall, thorny and undemanding plant the sweet fruit of which is popular in the Middle East. The name of the plant is tsabar in Hebrew, transliterated sabra in English, but the term is not primarily known among nature lovers. Indeed, sabra was also the name of the Israeli ‘new Jews’ in Palestine, which aptly describes the image of the idealized Hebrew man: hard and prickly on the outside, but tender-hearted and sensitive on the inside.

According to the concept, the sabra was a Jew born in Israel with a unique character: muscular, tanned, capable of agricultural work and military service, that is, all tasks from which Jews in the diaspora were often excluded. In early Israeli films, the sabras usually sat on jeeps or tractors, with rifles casually slung over their shoulders. Few people have described the Sabras as perceptively as the Hungarian-Jew Arthur Koestler, who immortalized the story of his years in Palestine in his novel Like a Thief in the Night. In his book, he described the new Jews born in Palestine as follows:

‘They were 19 years old, natives of the land, sons and grandsons of the first settlers of Petah Tikva, Rishon Letsiyon, Metula and Nahalal. Hebrew was their mother tongue, not an acquired skill; the land was their land, not a promise or fulfillment. Europe for them was a story of fear and terror, the new Babylon, the land of exile, where their forefathers sat by the river and wept. They were mostly blond, freckled, strong and ruggedly built; the sons of peasants and farmers, with a non-Jewish appearance. They weren’t haunted by bad memories and didn’t have to forget anything. They had no ancient curse and no hysterical hopes; they loved the land as only a peasant can love it, with the patriotism of a small child and the self-respect of a young nation. They were sabras.’[9]

In his book Promise and Fulfillment, he even added to the above that, in his opinion, ‘some kind of strange biological transformation’ was the reason for the blonde hair of Israelis, which he thought might have had ‘something to do with the soil.’ [10] The argument may seem irrational, but the results, if one can see a kind of causality between the goals of early Zionism and today’s Israeli society, in many ways justify Nordau. Although Israel is not particularly successful in international sports, the country has a strong performance in combat sports: judo is a sort of national sport, and Krav Maga is perhaps Israel’s most recognizable sports product. The Israeli army is considered to be one of the most capable armies in the world, and in this sense it was definitely possible to put the concept of muscle Jewry into practice.

And from another point of view, perhaps the development of Israeli society is not exactly the way the intellectual founding fathers dreamed it would be. While the writings about the new Hebrew man elevated the biblical longing for the land of Israel to a pedestal, the texts were generally secular, sometimes anti-religious. In contrast, in today’s Israel, religious Zionism plays a much greater role than before. In the early 2010s, some Israeli newspapers wrote about a ‘quiet religious revolution’ and the filling of military and public positions with religious people. According to Israeli demographic data, the increase in the non-aliyah (immigrant) population is primarily due to Orthodox Jews.[11]

From this point of view, it is worth comparing the representation of the various Zionist trends in the most widely circulated handbook of the sources of the ideological history of Zionism: written by rabbi and historian Arthur Hertzberg, it is his 1972 work entitled The Zionist Idea. Back then, research into the sources of socialist Zionism was still important, while the secular right received little space, and the religious right was only mentioned in passing. Nowadays, the order could perhaps be reversed: left-wing Zionism is barely alive, while right-wing secular Zionism has been dominant until now, but the previous Israeli prime minister was already something Nordau could never have envisioned: a kippah-wearing ex-officer of the IDF, Naftali Bennett.

[1] Pál Teleki’s speech dated 13 March 1928, in Felsőházi napló, Budapest, 1927, Vol. II., pp. 105-110.

[2] Raphaël Marchand, ‘Max Nordau. Juifs contre Juifs’, La Libre Parole, 21 Dec. 1903, pp. 1-2.

[3] Rudolf Spitzer [Lothar], ‘Antisemitische Caricaturen’, Die Welt, 1:3 18h May 1897, pp. 14-15.

[4] Noah J. Efron, ‘Trembling with Fear. How Secular Israelis See the Ulta-Orthodox, and Why’, Tikkun, 5:5, 1991, pp. 15-22, pp. 88-90.

[5] Dr. Herzl’s Evidence Before the Royal Brittish Commission on Alien Immigration, The Maccabean, August 1902, pp. 79-87.

[6] Max Nordau, ‘Speech to the First Zionist Congress’, (1897), in Arthur Hertzberg (ed), The Zionist Idea. A Historical Analysis and Reader, Philadelphia, JPSA, 1997, pp. 235-244, here p. 240.

[7] Michael Berkowitz, Zionist Culture and West European Jewry before the First World War, New York, Cambridge University Press, 1993, p. 107.

[8] Michael Brenner, Emancipation through Muscles: Jews and Sports in Europe, Lincoln, NE, University of Nebraska Press, 2006, pp. 16-17.

[9] Kösztler Artúr, Mint éjjeli tolvaj’, Budapest, Fabula, 1992, pp. 9-10.

[10] Arthur Koestler, Promise and Fulfilment. Palestine 1917-1949, London, Macmillan, 1949, p. 329.

[11] http://jewishweek.timesofisrael.com/the-haredi-revolution/