A peculiar episode of Mexican history, and an interesting junction between it and the history of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, is the short-lived Mexican reign of Maximilian von Habsburg. The archduke was invited to the throne of Mexico in 1863, after France invaded the country. It was an ill-fated enterprise as the emperor was executed in 1867, ending the brief history of the empire.

However, in order to understand this episode, it is important to look into the history of Mexico, and Mexican conservatism.

Conservative Genesis: Independence by Monarchy

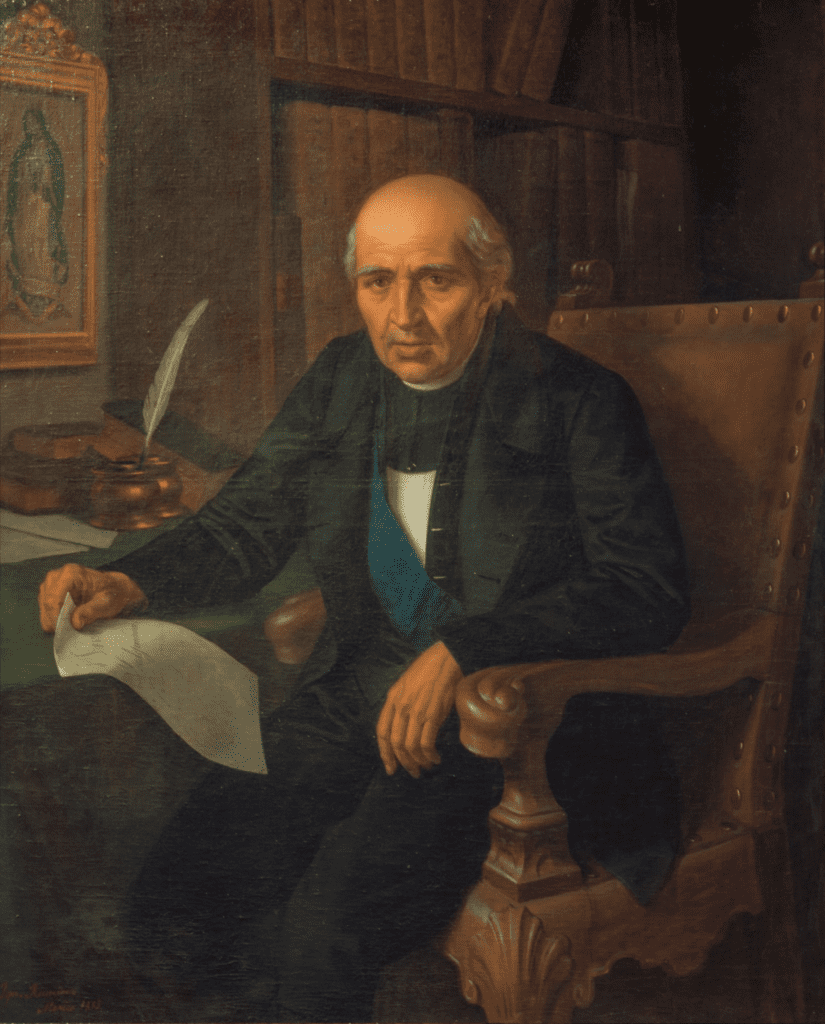

Mexico had been a Spanish colony for centuries when in 1810 a small group of rebels, led by a Catholic priest, Father Miguel Hidalgo, initiated an uprising for independence. The rebellion was swiftly suppressed by the Spanish army, and the rebellious priest was executed. However, the short-lived revolt sparked more resistance and ten years of fierce fighting ensued. The freedom fighters could not prevail until the local elites switched sides due to major changes in Spanish domestic politics. In 1812, the Cádiz parliament promulgated a liberal constitution, which sought to create a constitutional monarchy, taking away power from the colonial and local upper classes, concentrating decision-making in an elected Cortes (legislature) in Madrid, and of course, in the royal court. The constitution, the very first in Spain, and of markedly liberal character, is known as the ‘Constitution of Cádiz’.

The Mexican elites, however, opposed Cádiz. Their vision was the reverse of the constitution: an aristocratic and corporative autonomous Mexico within the Spanish monarchy, loosely governed by Madrid. Therefore, when the upper classes were forced to choose between a liberal-centralist Spain and an independent Mexico, they sided with the latter. Thus, in 1821, the leading figure of the colonial elite, Augustín de Iturbide offered a deal to the Mexican rebels: oust the Spaniards together, and in turn, create a conservative, monarchic and Catholic, independent Mexico. The deal was finalized in a document called the Plan de Iguala.

On 28 September 1821, Mexico was declared an independent empire.

Since no Spanish or European royal accepted the crown offered by the conservative elite, Iturbide himself took it, becoming emperor under the name of Augustín I.

The First Mexican Empire, however, swiftly collapsed in 1823, after renewed rebellions. Iturbide was exiled and eventually killed, becoming the first conservative martyr of Mexico.

The Partido Conservador

From 1823 onward, the Partido Conservador, the Mexican Conservative Party, became the vehicle of conservative politics. Their policies had a few core tenets, namely centralism, corporatism, and Catholicism. The conservatives believed that giving too much power to the provinces would create discord and inflame civil wars. This group also argued that Mexico, as a colony, never had extensive provincial autonomy. Monarchism, on the other hand, became a fringe ideology after the fall of the First Empire, although it never ceased to be part of Mexican conservatism.

Regarding representation, the conservatives preferred corporatism as opposed to democracy. Thus, they sought to create a legislative body that would represents each social class. It was especially crucial for them to give a strong voice to the clergy and the military, since conservatives saw these elements as the backbone of Mexican society. In fact, conservatives also supported upholding the colonial privileges, the so called fuerros, of these groups, for instance the right to be tried by special courts. The conservatives believed that Mexico should remain a Catholic nation. In fact, one of the conditions laid down in the Plan de Iguala was that despite the separation from Spain, Mexico’s state religion must remain Catholicism.

Chaotic Years and La Reforma

After the fall of the First Mexican Empire, and the formation of the party, the conservatives used both political and military tools in their attempts to dominate the country. In doing that, conservatives were no better than the liberals: Mexico’s hectic early nineteenth century history was characterized by fast-changing administrations, often ousted by coups or countercoups.

Staging a violent revolt was both a more common and a more successful path to power in Mexico than electoral politics.

In 1835, the conservatives gained a firm and, at least by contemporary Mexican standards, long-term hold on power, establishing the so called ‘Centralist Republic’, which was in fact a military dictatorship lasting from 1835 to 1846. This era was defined by the centralization of the provincial governments, and a supposedly stable governance, which was nevertheless plagued by constant liberal uprisings. The most important conservative leader of the time was President Antonio López de Santa Anna, the Mexican hero and American villain of the Battle of Alamo. While initially successful in suppressing the Anglo-Saxon rebels in Texas, the dictator could not prevent the Lone Star State from seceding. Similarly, Mexico also lost the Mexican American War in 1848. The defeat led to the loss of substantial territories to the United States, and it also swept the conservative government away.

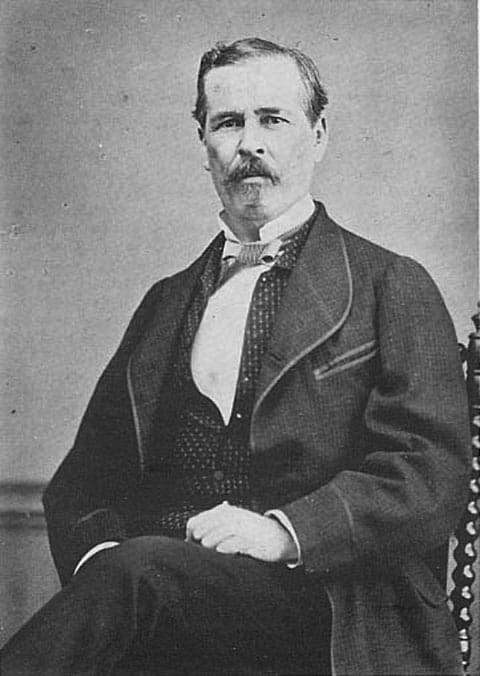

The succeeding liberal government initiated wide-ranging reforms, known in Mexico as the era of ‘La Reforma’. In 1857, their most renowned leader, President Benito Juárez drafted a new basic law for the nation. The new constitution established Mexico as a democratic and secular state, stripping the church of its privileges, and more importantly, chipping away at its vast estates. Similarly, it did away with military and other privileges, creating equality before the law. The liberals also initiated a land reform, mandating the breakup and sale of not only church, but also communal lands owned by the Mexican Indian community. Furthermore, the liberals expanded the autonomy of the provinces.

Forever Wars

The liberals hoped that political liberalization, coupled with the liberalization of land markets, would accelerate foreign investment and economic growth in Mexico. However, the liberals did not succeed in stabilizing the country. In 1857, a conservative general, named Felix Zuloaga, declared himself president, starting the so called ‘Reform War’. Mexico was engulfed in yet another bloody, but indecisive conflict for the next mor than four more years.

As neither of the parties could prevail in the fight, Zuloaga could not execute his Tacubaya Plan, which called for a new constitutional assembly that would have revised the constitution, curbing liberal extremes, while not reinstituting the full status quo ante. The liberals, on the other hand, were unable to enforce the 1857 Constitution or to continue the secularization of the church and the privatization of Indian landholdings. But what the war did achieve was the destruction of the infrastructure and economy of Mexico. On top of all that, the liberal president, Benito Juárez suspended payments on debts to the European powers. To enforce their claims, France, Spain, and the United Kingdom invaded Mexico in 1861.

Two of these powers only wanted their money back. So, when Juárez made some concessions, Spain and the United Kingdom pulled their troops out. French Emperor Napoleon III, however, had different plans. Pursuing the Bonapartist ideals of gloire and grandeur, he aimed to expand his realm’s influence globally. Therefore, France continued with the land invasion, pushing toward the interior of Mexico. He also found allies among the Mexican conservatives. So the Reform War never ended, but was rather transformed into an international conflict, known as the French Intervention in Mexico.

Soon the French and the conservatives occupied Mexico City, and the central regions of the country.

To lend legitimacy to their project, the French established the Second Mexican Empire,

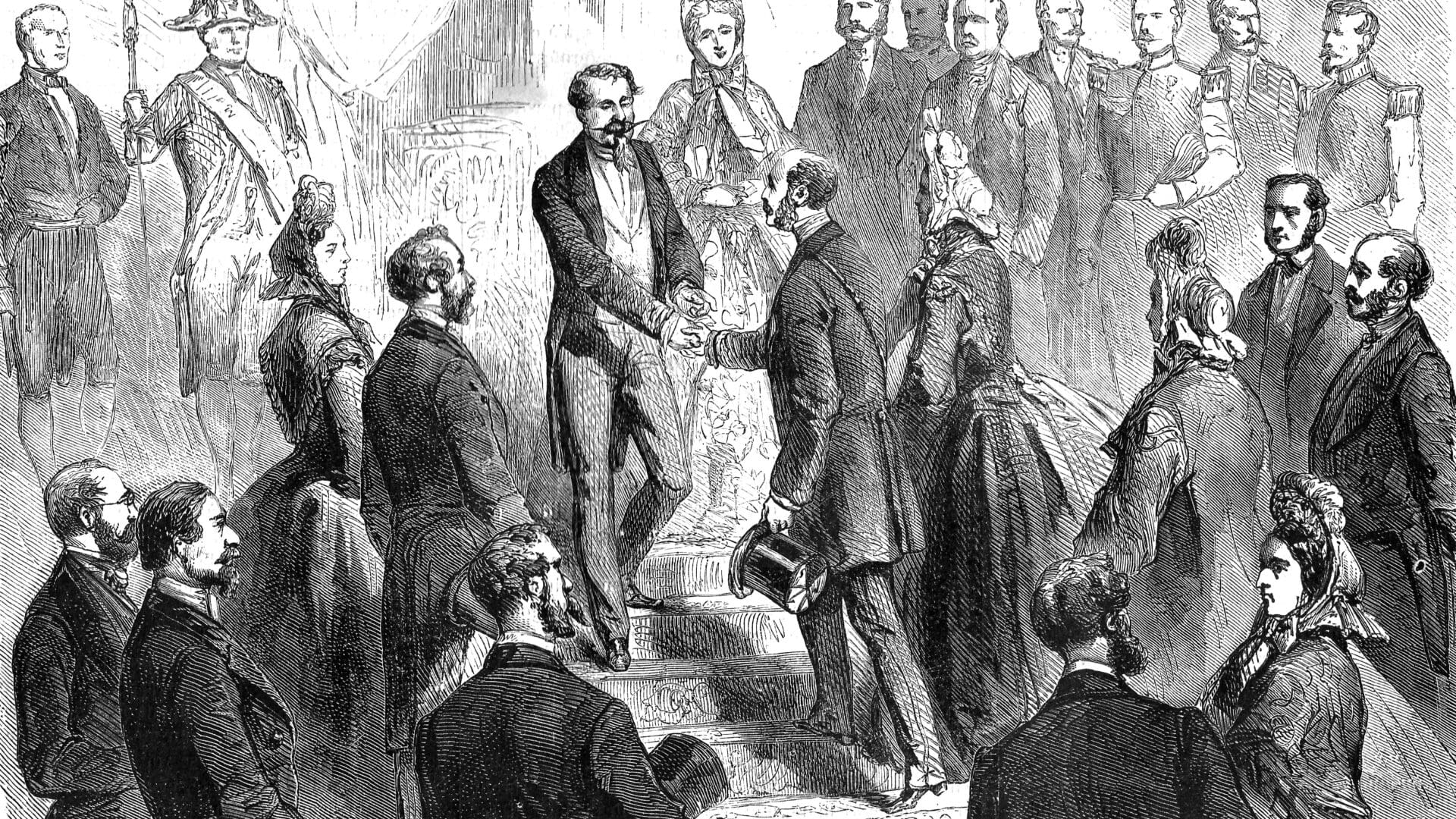

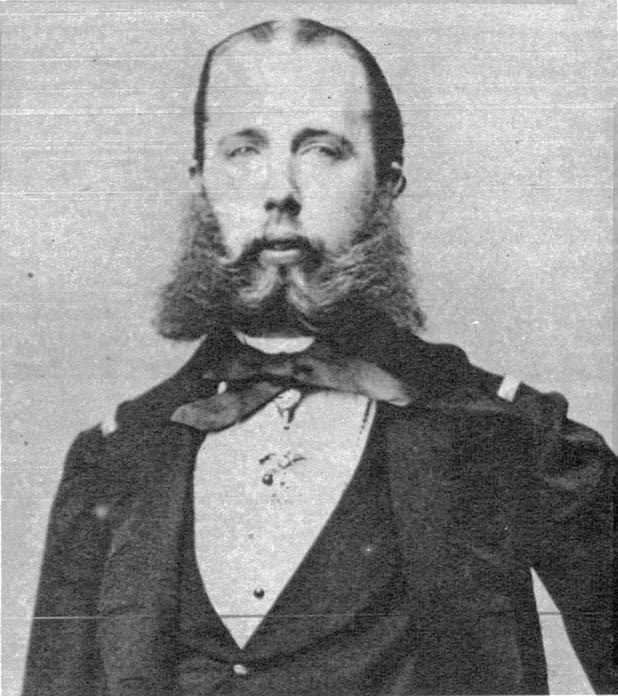

as a constitutional monarchic alternative to the liberal republic of Juárez. In 1863, the new monarchy was officially declared, the (conservative) legislature electing a regency council, headed by Juan Almonte, a conservative politician. After a brief period of searching, the legislature chose a European archduke to offer the crown to: Ferdinand Maximilian Josef Maria von Habsburg-Lothringen, or simply: Maximilian of Austria, the brother of Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary Francis Joseph.

Maximilian accepted the crown, and landed in Mexico in 1864. With his arrival, a brief, but eventful new era commenced for the country.