One of the oldest cemeteries of medieval and early modern Kecskemét was discovered during the beginning of the latest phase of the renovation of the Kodály Institute of the Liszt Ferenc Academy of Music in Kecskemét, archaeologist András Kristóf Fazekas announced.

The archaeologist, who is also the curator of the Kecskemét Katona József Museum, recalled that the Franciscan order was gifted the area of the site in the 1640s, and they built several, presumably wooden buildings there, but the complex burnt down in 1678. The construction of the still-standing baroque-style, square-shaped monastery began after the fire in the medieval centre of Kecskemét.

However, the tower-like protrusion is much older. Based on the keyhole-like loopholes, it was presumably built in the early 1400s. During the excavation, archaeologists unearthed this core preserved between the foundation walls.

The current excavation extends beyond the former monastery walls in the centre of Kecskemét, continuing along Kéttemplom Square. The area excavated in recent weeks was only 15 square metres large and was archaeologically well-known. From the second half of the 14th century until 1778, this area, located in today’s Romkert (Ruins Garden), stretching from the Calvary in front of the church to the entrance of the Kodály Institute, was one of the oldest cemeteries in medieval and early modern Kecskemét.

In the late 18th century, Maria Theresa’s decree ended burials within the city and designated new cemeteries outside the city limits.

During the excavations, experts uncovered and collected a significant quantity of human bones, finding intact or partially preserved skeletons in 18 sections.

According to András Kristóf Fazekas, the significant disturbance was caused by centuries of graves being reused, and the construction of the north-eastern wall of the monastery in the early 18th century, as the deceased were not exhumed then. Finally, in modern times, earthworks related to various constructions and utilities infrastructure also disturbed and destroyed graves. Fazekas explained that timber remains and coffin nails have been found, indicating that the deceased were buried in wooden coffins. The orientation of the skeletons was uniformly southwest-northeast, matching the orientation of the church.

Archaeologists mostly found remains of infants and children among the excavated graves.

This can be primarily explained by the fact that they were exploring the upper layers of the cemetery, and based on previous experiences, shallower graves were dug for the young, thus their remains lay higher.

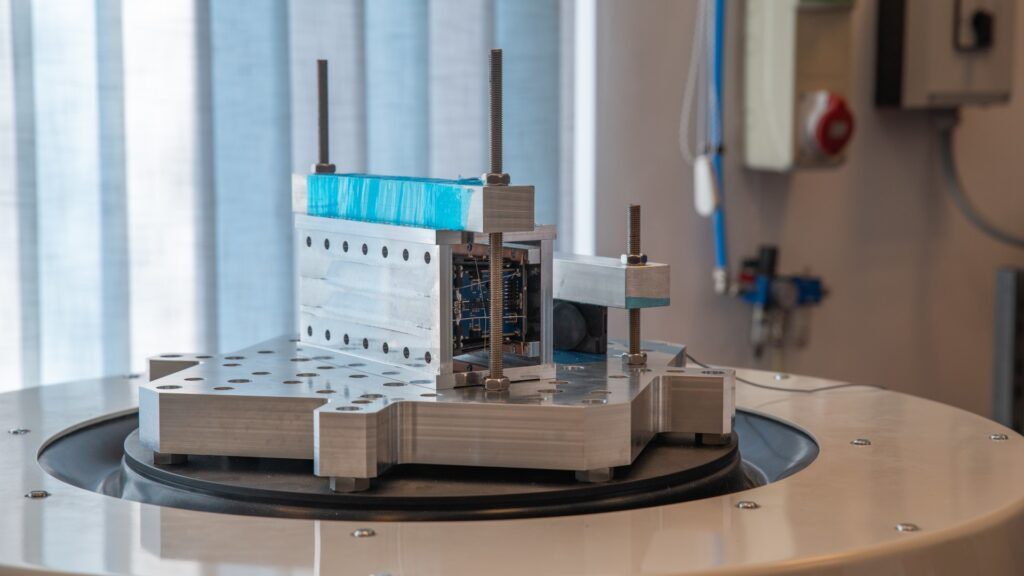

One of the excavated graves stood out as a burial place for an infant. The grave of the little girl, whose body had disintegrated from the chest down, lay high, about 70 centimetres deep from the current ground level, almost directly beside the sanctuary of the church. Despite her short life, an ornate, bronze-spiralled beaded headband was placed on her head at the time of burial. According to the expert opinion of archaeologist Orsolya Zay, headbands of this type were used in the 1600s.

The skull and headband were excavated and preserved together, allowing for the possibility that the headband of the girl who once lived may regain its original beauty in the workshop of a restorer, András Kristóf Fazekas added.

Read more:

Sources: Hungarian Conservative/MTI