When Hungary’s highest-ranking Coptic priest walked through the door of our recording studio back in July to be interviewed for the Danube Institute podcast, none of us really knew what to expect.

After all, Abouna Youssef Khalil may be a man of the cloth (quite literally, as he never sets aside the black robes and large neck-worn cross of his office), but he is also somewhat of a renaissance man. His title, Abouna, literally means ‘our father’ in Arabic, and indicates his status as a priest. More accurately, he is an archpriest, which is the highest possible rank attainable for non-monastic clergymen in the Coptic Church. Although we were interested in Abouna Youssef’s story as the principal founder and leader of the Coptic Church in Hungary, we knew he also had other stories to tell.

Coptic Orthodox Christianity is unfamiliar to most European countries. Although it is sometimes confused with the Eastern Orthodox faith of Greece or Russia, which became separated from Roman Catholicism after the East-West Schism in 1054, Coptic religion traces its origin back to an earlier divide. The Coptic Church was one of several that split off from the Imperial Roman Church when it rejected the decisions made at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 (along with the Armenian and Ethiopian churches, among others). These churches are collectively known in English as Oriental Orthodox, rather than Eastern Orthodox, and their requirements for joining the priesthood are mostly similar. To be a priest, one must be married, have good standing in the community, achieve excellence in one’s career, have many years of service in the church, and receive a nomination from senior colleagues in one’s own church community.

In his past life as a medical doctor and expert surgeon, Abouna Youssef spent ten years in Egyptian operating theatres, saving the lives of his many patients, both Christian and Muslim. His command of languages goes beyond his impeccable English and native Arabic; he also speaks decent Hungarian, and like most others in his position, is proficient in Coptic (the original language of Ancient Egypt and the liturgical language of his church) as well as Biblical Greek and Hebrew. When interviewing someone with so many titles and roles—a priest, a husband, a parent, a spiritual leader and a doctor—you can never be sure where the conversation might take you.

And so it was that, to no one’s surprise, we found ourselves intrigued by what we heard.

After the end of Communism in 1990, a small number of Coptic Egyptians began coming here

Abouna Youssef spoke about the history of Hungary’s Copts. In the beginning, there was no Coptic community to speak of. After the end of Communism in 1990, a small number of Coptic Egyptians began coming here, seeking to work hard and help build a country that had before been unfriendly to Christianity as a result of its Marxist state ideology. Former Coptic Pope Shenouda III personally called Abouna Youssef to be the shepherd to this burgeoning community in the early 2000s, and after a slow but steady growth in the years since, Pope Shenouda visited Hungary to consecrate the nation’s first and only Coptic Church. It was his last such ceremony, as Pope Shenouda passed away less than a year later in 2012. He is still mourned and remembered by his Hungarian flock.

Abouna Youssef spoke openly about his experiences and recollections of those early days. Some were amusing, some sobering, while others were more challenging. One story even encapsulated all three of these. 15 years ago, while he was attending the ceremony for his daughter’s graduation from secondary school, an unnamed person pointed at Abouna Youssef, shouting ‘bin Laden!’ Abouna Youssef waited quietly for the clamour that ensued to calm down, before approaching the individual to introduce himself and explain what his priestly robes signified. He jokingly recounted as saying: ‘If bin Laden was wearing a cross like mine, it would be quite a miracle!”

But more than anything else, what transpired from our interview was Abouna Youssef’s unambiguous appreciation of Hungary for its openness and acceptance of religious minorities. A cynical reader might presume the archpriest’s praise was just a shallow compliment, but that is not the case. Abouna Youssef has been asked in many interviews about his feelings regarding Hungary’s acceptance of religious and ethnic minorities over the years, but his message has been consistent throughout. Anecdotally speaking as a member of his congregation, my own personal experience in private and in public are further affirmative of his conviction on this matter.

But at the same time, his perspective, and its positive affirmation of Hungary as a tolerant society, seems to fly in the face of the negative consensus established in the international media over the past decade. It is this consensus, fomented in no small part by foreign journalists and media moguls with little-to-no in-depth experience of the nation, which depicts Hungary as an intolerant, undemocratic, ultra-Catholic nation; one where religious minorities are unwelcome and unwanted.

A quick Google search should be sufficient to see what I mean. Western media outlets such as the BBC, CNN, and the New York Times have been proactive in charging Hungary with antisemitism, bigotry, and intolerance. A 2019 POLITICO article entitled ‘Viktor Orbán’s anti-Semitism problem’ ran with the subheading ‘Trump’s guest at the White House is no friend to the Jews.’ Further examples can be found in The Guardian, which once accused the Hungarian government of being a ‘quasi-theocracy’—one that ‘deploys’ Catholic Christianity as a kind of political weapon at the expense of minority groups. The articles of this genre are remarkably consistent. No matter where they are published or who writes them, the underlying message is that Hungary is not a friendly place for those who believe or pray differently from its Calvinist prime minister.

This is the story we are told, and the story we will be told, time and time again. But it is not the full story, and a short walk through Hungarian history can help to remind us of that.

Over a millennium ago, in the year 1000 AD, St Stephen (known in Hungarian as Szent István) was crowned with the Roman Papacy’s consent as the first king and Christian ruler of what would then be known as the Kingdom of Hungary. Before his baptism and coronation, St Stephen had been known as Vajk, a pagan prince of one of many Hungarian tribal factions in the Carpathian basin. In the following century, Hungary’s religious demography rapidly changed, resulting in the emergence of a consolidated Hungarian nation that was predominantly Christian, and Catholic. The Hungary of today is similar to what St Stephen established: a predominantly Catholic, Christian nation. But it wasn’t always so simple.

Over the years, the new kingdom’s Muslims and pagans gradually converted to Christianity

In the centuries that followed St Stephen’s coronation, Hungary remained home to non-Christians—not only pagans, but also flourishing Jewish communities as well. There were even small Muslim communities, known in Hungarian as Böszörmény, which arrived during or shortly after the initial Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin.1 Over the years, the new kingdom’s Muslims and pagans (including the Cuman refugees of the early 1200s fleeing from the Mongol onslaught) gradually converted to Christianity, in a slow process that was notably peaceful and voluntary for its time.

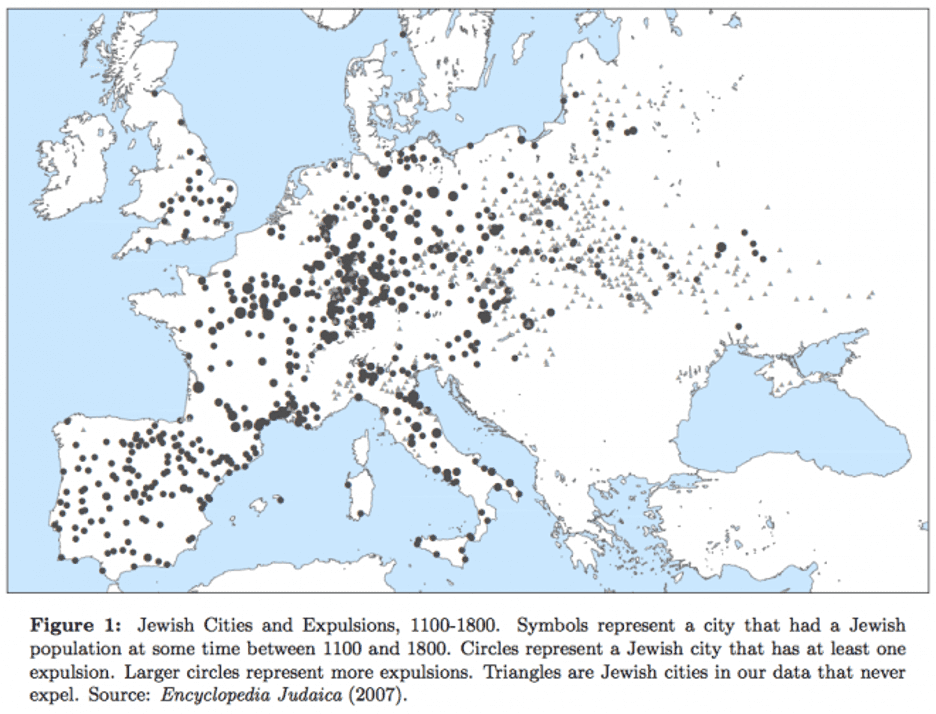

Certainly there were laws restricting the freedoms of religious minorities, and it would be wrong to suggest that early Hungary constitutes some kind of ‘confessional utopia’. But it is noteworthy that during the centuries which saw Jews persecuted in Western Europe, Muslims forcibly expelled from Spain, and Christians forced into oppressive, poverty-inducing taxation in the Middle East, Hungary’s religious minorities could enjoy the freedom to participate in wider society, and were not as a rule forced into conversion or assimilation at the point of a sword (a wicked practice that was a rule, rather than an exception, for the age).

After the Protestant Reformation, and subsequently the Ottoman Turkish invasions, the Hungarian landscape lost any semblance of religious uniformity for some time. Historian Miklós Molnár writes that during this period (known by historians as ‘the withering of the Magyars’) a combination of ‘war, epidemics, the plague’ and possibly even a ‘mini ice age’ brought a temporary end to Hungary’s flourishing, literate, and open-minded civilisation.2 Tragically, ethnic and religious tolerance became the first casualties of the decline; a sad but predictable trend that seems to appear throughout history in virtually all nations, once war, poverty, and instability take their toll on civil society.

Yet Hungary fared better than many of its European counterparts of this age, and the colossal religious wars of the 16th and 17th centuries left it relatively unscathed. Although outbreaks of interfaith violence did occur in this period, Molnár argues that these were never more than exceptions to the rule. On the whole, ‘the spirit of tolerance survived’ in Hungary, at a time when Europe’s Wars of Religion were in full swing, and Catholics, Calvinists, and Lutherans were tearing each other apart.3

Subsequent centuries saw the Ottoman Caliphate driven back, and the Hungarian lands began a slow (and arguably, still unfinished) process of recovery, albeit under the hegemony of the Austrian Habsburgs. From the mid-1700s onward, Hungarians found themselves in a religiously diverse yet largely peaceable society. They shared this society with Orthodox Ruthenians and Romanians, Catholic Croatians and Czechs, Lutheran Saxons and Schwabs, and Reformed communities centred in Eastern Hungary and Transylvania. Finally, there was the sizable Jewish minority, which thrived especially around Budapest. This city, the nation’s capital, would eventually become the birthplace of Jewish titans such as John von Neumann, Paul Erdős, and Theodor Herzl, the Father of Zionism. It seems nothing short of a miracle that this incredibly diverse list of groups was able to live together and get along—yet for the most part, that is exactly what they did. That being said, infrequent outbreaks of pogroms and ethnic riots were an occasional problem, and state authorities responded to these with extremely harsh punitive measures.

This ethos of tolerance (helped along by state support) once again found itself challenged after the collapse of Austria-Hungary at the end of World War I, when ethnic minorities like the Slavs and Romanians began to agitate for the collapse of the Kingdom of Hungary, actively supporting its division and territorial breakup in favour of their own new ethnic nationalist states. Simultaneously, the continent was struck by an explosive wave of violent revolutions, most of which were communist in character, further polluting Hungarian society with panic and distrust.

Hungary’s Jewish community, being largely urbanite and well integrated, stood to gain nothing from this chaos; unlike other minorities, Jews had no desire to see an ethnostate of their own carved out of Hungarian lands. Nevertheless, Jews became the primary victims of this chaotic period all the same. Much like in Germany, Poland, and Ukraine, Hungary suffered an explosion of pogroms around the country, some of which were severe. Yet scholars such as Béla Bodó have noted that at this time, there were active attempts by Catholic leaders to suppress antisemitism and the roving militias, despite some opposition from extremist minorities.4

The situation of ethnic minorities in Hungary continued to deteriorate throughout the years to come

Despite these attempts, the situation of ethnic minorities in Hungary continued to deteriorate throughout the years to come. After Regent Miklós Horthy was overthrown in a Nazi-instigated coup, the country fell under German domination. Shortly after, it became an active participant in the events now known as the Holocaust, within which more than half a million Hungarian Jews were murdered. One of these victims was Miklós Radnóti—a Jewish poet who was an outspoken Hungarian nationalist, and had together with his wife converted to Catholicism some years before. His fate is a crime so patently insane that it can be taken as a metaphor for the Holocaust itself. One of Radnóti’s most famous poems, Nem Tudhatom (or ‘I cannot know’ in English) was composed in 1944. Radnóti describes in this poem his impotent fury toward the German-backed fascists (the Arrow-Crosses) who claimed to be ‘true Hungarians’ but were in his mind little more than ignorant foreigners; thugs who did not love or even know the land they now ruled with violence and brutality. Radnóti, conscripted to a Jewish labour battalion in the Hungarian military, was force marched towards Germany, starved and beaten and eventually shot dead by those thugs in that very same year.

The madness was finally ended by Hitler’s demise and German defeat in World War II. After the war, Hungary began to recover, rebuilding its destroyed infrastructure and economy. But remarkably, Hungarian culture, too, began to recover—and with that came the restoration of age-old values and attitudes, such as the value of religious toleration and acceptance. Hungary today is a country that enshrines the freedom of religion, as well as the freedom from religious discrimination, in its constitution. In a sense, the constitution is doing far more than affirming what Hungary is today; it is reaffirming what Hungary always was, and what it has fought for time and time again.

But will Hungary’s fledgling Coptic community—who speak Arabic and are far apart from other religious groups in the country by virtue of being Oriental Orthodox—be afforded the same standards of equal treatment? Or is such a hope little more than naïve optimism?

As it just so happens, history has a precedent for this matter. Coptic Christianity may seem new to Hungary, but the Oriental Orthodox communion to which it belongs certainly isn’t. After the Ottoman Turks conquered Constantinople and extinguished the Byzantine Empire in 1453, countless thousands fled as refugees to the West—some coming to Hungary. Many refugees were Armenians, whose Oriental Orthodox faith is shared by the Coptic newcomers of today. While most have long since assimilated, there is still a small minority of ethnic Armenians in Hungary, including government junior minister Tristan Azbej—whose presence in this country provides a living testament to this historic tradition of tolerance and acceptance.

And so it is that an Egyptian priest can remind us of Hungary’s present, as well as its past. Accepting religious diversity isn’t something that Hungarians need to be told to do in the classroom, or in advertisements, or on some celebrity’s instagram page. It’s something they’ve been doing for a thousand years, as any Copt in Budapest will tell you.

Our podcast with Abouna Youssef Khalil is available on spotify through this link. Special thanks to Distinguished Fellow Jeffrey Kaplan, and colleagues Sáron Sugár and Lídia Papp, for making this interview possible.

NOTES

1 Raphael Pati, The Jews of Hungary, Detroit, 1996, 42.

2 Miklós Molnár, A Concise History of Hungary, Cambridge, 2014, 96.

3 Miklós Molnár, A Concise History of Hungary, 109.

4 Béla Bodó, ‘Responses to Terror’, in Anti-Semitism in Hungary: Appearance and Reality, edited by Jeffrey Kaplan, Zsófia Tóth-Bíró, Lídia Papp, Tamás Orbán, Dávid Nagy, Reno NV, Helena History Press, 2022, 70.