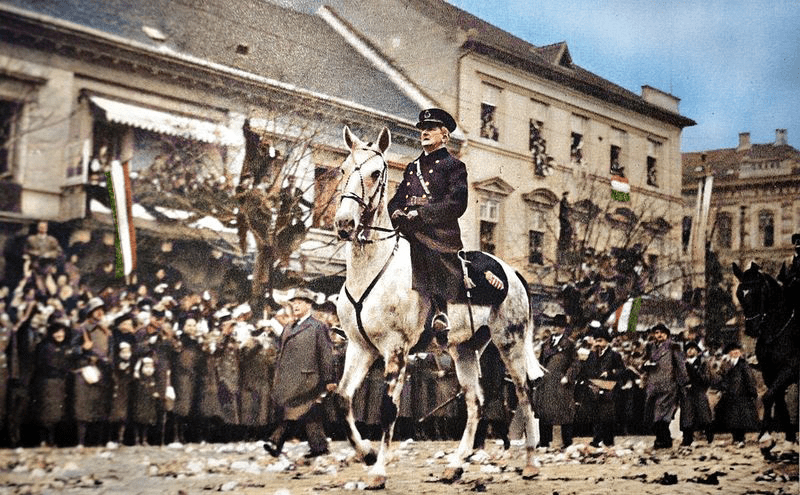

Miklós Horthy was born today, 18 June, 155 years ago. The anniversary provides an opportunity to overview the life and career of the Regent, whose controversial legacy still arouses passions and who more often than not is unfairly judged by posterity.

The Horthy family received a certificate of nobility in the middle of the 17th century. Miklós Horthy’s father, István Horthy, was a member of the House of Magnates (Főrendiház in Hungarian), the upper chamber of the Diet of Hungary.

By his own decision, the younger Horthy enrolled in the Maritime Academy in Fiume (today Rijeka, Croatia) in 1882, where only 42 of 612 applicants were accepted. There, he learned Italian and Croatian. In addition, he spoke German, English, and French fluently as well. On 7 October 1886, he was inaugurated as a sub-lieutenant of the Austro-Hungarian Navy. Then, between 1909 and 1914, he served as Franz Joseph’s aide-de-camp. During World War I, he became a rear admiral, then vice admiral under the newly crowned Charles IV of Hungary. Besides,

Horthy was the last commander-in-chief of the Austro–Hungarian Navy in the last year of WWI.

By the end of WWI, even the highest-ranking officers and politicians of the countries hostile to Hungary had a good opinion of Horthy. During the time of the 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic, he joined the counter-revolutionary organisation in the town of Szeged, which was under French occupation at the time. On 31 May 1919, he became Minister of War in the Szeged-based counter-revolutionary government led by Count Gyula Károlyi, a former Prime Minister of Hungary. Horthy also played a significant role in Béla Kun’s Communist government being forced to flee the country after their 133-day reign of terror.

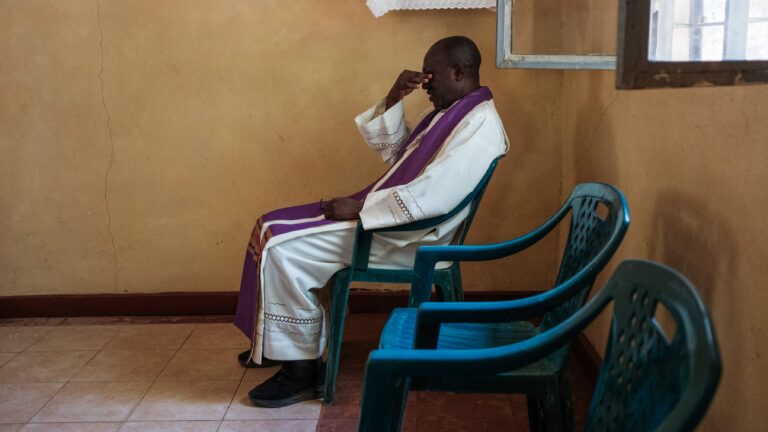

Miklós Horthy served as the Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary between the two world wars,

from 1 March 1920 to 16 October 1944. He realised with good sense that aiding a Habsburg ruler to take the throne could have had tragic consequences for the country. After the Treaty of Trianon, the winning powers of World War II and the Little Entente countries that received territory from Hungary (Kingdom of Romania, Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, and Czechoslovakia) believed that Hungary would perish as a result of the punishments imposed on her. However, the Regent played a huge role in making the truncated country not only survive the trauma, but also show signs of development within a short time.

Hungarian foreign policy in the period between the two world wars was determined by the goal of territorial revision, that is the ambition to recover the parts of the country lost after WWI. In 1938, the southern part of Upper Hungary, in 1939, Transcarpathia, in 1940, Northern Transylvania, and in 1941, a part of Vojvodina were returned to the mother country as a result.

After WWI, Hungary was forced onto an economic and political path that ultimately led it toward Nazi Germany in the early 1930s. At the beginning of WWII, Regent Horthy tried to pursue a pro-English policy and remain militarily neutral, but in the end—for various reasons—he succeeded in doing neither.

In 1941, he finally committed himself to the Axis Powers.

Deeming Hungary an unreliable ally, on 19 March 1944, Nazi Germany occupied the country, thus Horthy’s room for manoeuvre was completely narrowed. The deportation of Jews from the countryside shortly began, and those from the capital soon followed. Horthy only intervened and stopped the deportations in the middle of the summer of 1944.

In October 1944, he tried to lead his country out of the war, however, the occupying Germans kidnapped his son, so, yielding to the blackmail, he agreed to step down and the attempt to exit the war failed. The Regent and his family were taken to Germany and held prisoner. Horthy’s only surviving child (he had previously lost his two daughters and his son István, an air force officer intended to be deputy governor, in tragic circumstances)

was transported first to the Mauthausen, then to the Dachau concentration camp.

In March 1945, Heinrich Himmler ordered the execution of the Regent and his whole family, which did not happen only because the SS guards holding the family prisoner dressed in civilian clothes and fled before the arrival of the American troops.

During the Nuremberg trials, no charges were brought against Horthy—he was only interrogated as a witness. After the war, he retired from political life and settled in Estoril, Portugal with his family. The Soviet suppression of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 took a heavy toll on the elderly Miklós Horthy, which may have contributed to his passing away, despite having no physiological disorder or serious illness, on 9 February 1957.