This article by Dániel Gyuriss was published in Hungarian on Corvinák, the knowledge base of the Mathias Corvinus Collegium.

The provocative removal of the Turul monument in Mukachevo (officially Mukachiv, formerly Munkács, Hungary) has provoked strong feelings in Transcarpathia and Hungary. Various explanations have been offered as to the reasons for the taking down of the statue, and the causes have posed new challenges to Hungarian-Ukrainian relations, which have been on a downward trend.

On 13 October 2022, the Ukrainian-majority Mukachevo City Council decided to remove the Turul sculpture, which had been re-erected in 2008, and replace it with a triple trident, the Ukrainian state emblem. Two hours after the decision to remove the statue was taken, the historic Hungarian symbol, which had been cut into pieces, was being hurriedly thrown into the moat by workers.

On 25 October, the Ukrainian symbol on the obelisk of the former Turul monument was unveiled and handed over by the Mayor of Mukachevo, Andriy Baloga. The mayor justified the installation of the symbol as a tribute to the country’s defenders and said: ‘Ukraine is more united than ever. Ukrainians are only getting stronger and will fight to the end, to victory.’ The mayor’s father, Viktor Baloga, who is a member of parliament, echoed his son’s arguments for the sculpture’s removal, including that ‘the statue of the Market Square in Mukachiv was a symbol of Hungarian dreams of great power and irredentism.’

According to the politician, the Hungarian political elite is trying to block sanctions against Russia by all means, deliberately and systematically obstructing Ukraine’s European integration, while at the same time constantly supporting the Kremlin’s masters.

He also said that ‘all the symbols and spirit of Greater Hungary must be abolished once and for all’.

Karolina Darcsi, the communications secretary of the Hungarian Cultural Association of Transcarpathia (KMKSZ), said in response to a press enquiry that the Baloga family is known throughout the country for its good relations with Russia. ‘This Russian line is becoming more and more embarrassing; they have been repeatedly attacked in the Ukrainian press for this, so the removal of the statue is presumably just a means to get rid of this stigma.’ Darcsi also noted that the act could be interpreted as a message to the public.

Earlier, the monument commemorating the conquest of the Carpathian Basin at Verecke, also erected in 2008, was targeted by Ukrainian extremists as well.

After it was completed, the monument, which is a tribute to the Hungarian tribes that conquered the Carpathian Basin around a thousand years ago, was repeatedly vandalised. After the inauguration, members of the Svoboda party placed a trident on the upper side of the monument and inscribed their own text on a marble plaque. It read: ‘Monument to the repentance of the Hungarian people for the murders committed by the fascist occupiers in 1939–44. Eternal glory to the heroes of Ukraine — the Carpathian Sich Guards’. In 2011, on the 20th anniversary of the proclamation of Ukraine’s independence, the Ukrainian trident symbol was placed on top of the monument by activists of the same, extremist Svoboda party. This symbol was dismantled by the authorities when the statue was restored.

A recurring element in both cases is the main symbol of the Ukrainian coat of arms. This symbol was in use between the 10th and 12th centuries in the territory of the Kievan Rus under the Rurik dynasty. The symbol also appears on the coin of Prince Vladimir the Great of Kiev. While the exact meaning of the symbol is unknown, the best known theories are that it could represent the Holy Trinity, a bow and arrow, a candle, an anchor or even the wings of a falcon. The trident reappeared in 1918, when, after the collapse of Tsarist Russia, the People’s Republic of Ukraine, which existed from 1917 to 1920, made it the official symbol of the republic and put it on banknotes. Finally, in 1992, the trident again became the central motif of the coat of arms of Ukraine.

The cases of Mukachevo and Verecke are in themselves a striking example of the intent Ukrainian politicians and their supporters had: to display their own political agenda and serving nationalist political goals. The difference between the two cases can be best illustrated by the fact that the destruction of images in Verecke was a grassroots, clearly illegal act, whereas in Mukachevo the statue was removed as a result of a decision by the local authorities, a decision from above in terms of power, which appeared to be formally legal. This latter fact clearly makes it difficult to call for an investigation into the matter or pursue the restoration of the monument, especially if Kyiv does not support such Hungarian demands.

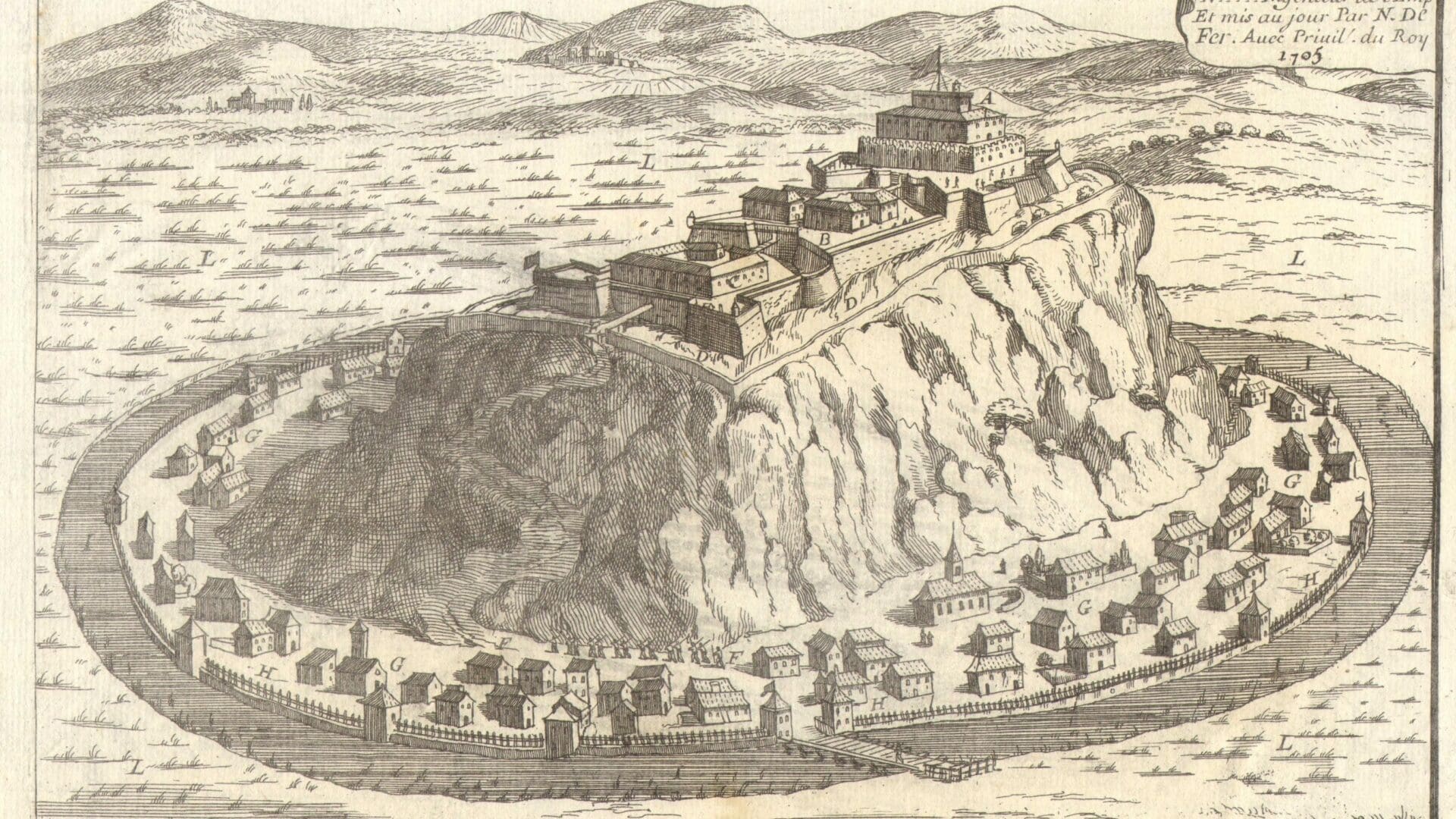

Thus, the Ukrainian symbol of negligible artistic on top of the obelisk of the mutilated Turul monument in Mukachevo is set to remain in place for quite some. The size of the Ukrainian trident compares to the magnitude of the massive castle the same way decades of Ukrainian rule compare to the one-thousand-year-old Hungarian history in Transcarpathia. It can be seen as a symbolic compensation, a shock therapy that tries to deal with the frustration caused by the sense of difference between the Hungarian historical past of the region and the Ukrainian present, under the guise of political reasons.

However, it is also worth noting that alongside the symbolic occupation of space associated with Ukrainian nation-building, a practice has also emerged that adapts central instructions to local levels. In 2015, the Ukrainian legislature passed a law of decommunization, ordering the banishment of relics of the communist past from public spaces across the country. As a result, many streets and squares have been since renamed after great Hungarian historical figures such as Ilona Zrínyi or Ferenc Rákóczi, while in several cases old Hungarian names have been restored (such as Rövid and Széna Squares). At the same time, many streets were named after the victims of the 2014 fighting in Eastern Ukraine, to pay tribute to them as war heroes. This also brought to the fore the local memory of the war that raged in another part of the country.

While the 2015 solution was one of compromise that took into account the needs of the local Hungarian community, the destruction of symbols and the subsequent symbolic reinterpretations of history in Verecke and later in Mukachevo, motivated by specific political agendas, completely neglected them. All this was done while Hungary and Ukraine signed a bilateral treaty on the mutual protection of each other‘s national cultural heritages, which are also protected by international treaties signed under the auspices of UNESCO. Unfortunately, it seems that this reciprocity and the desire for good relations have also become a victim of the Russo-Ukrainian war, which is a painful development for Hungary.

Click here to read the original article