This article was originally published in Vol. 4 No. 3 of our print edition under the title ‘International Perspectives on the Protection of National and Ethnic Minorities in 2024’.

Introduction

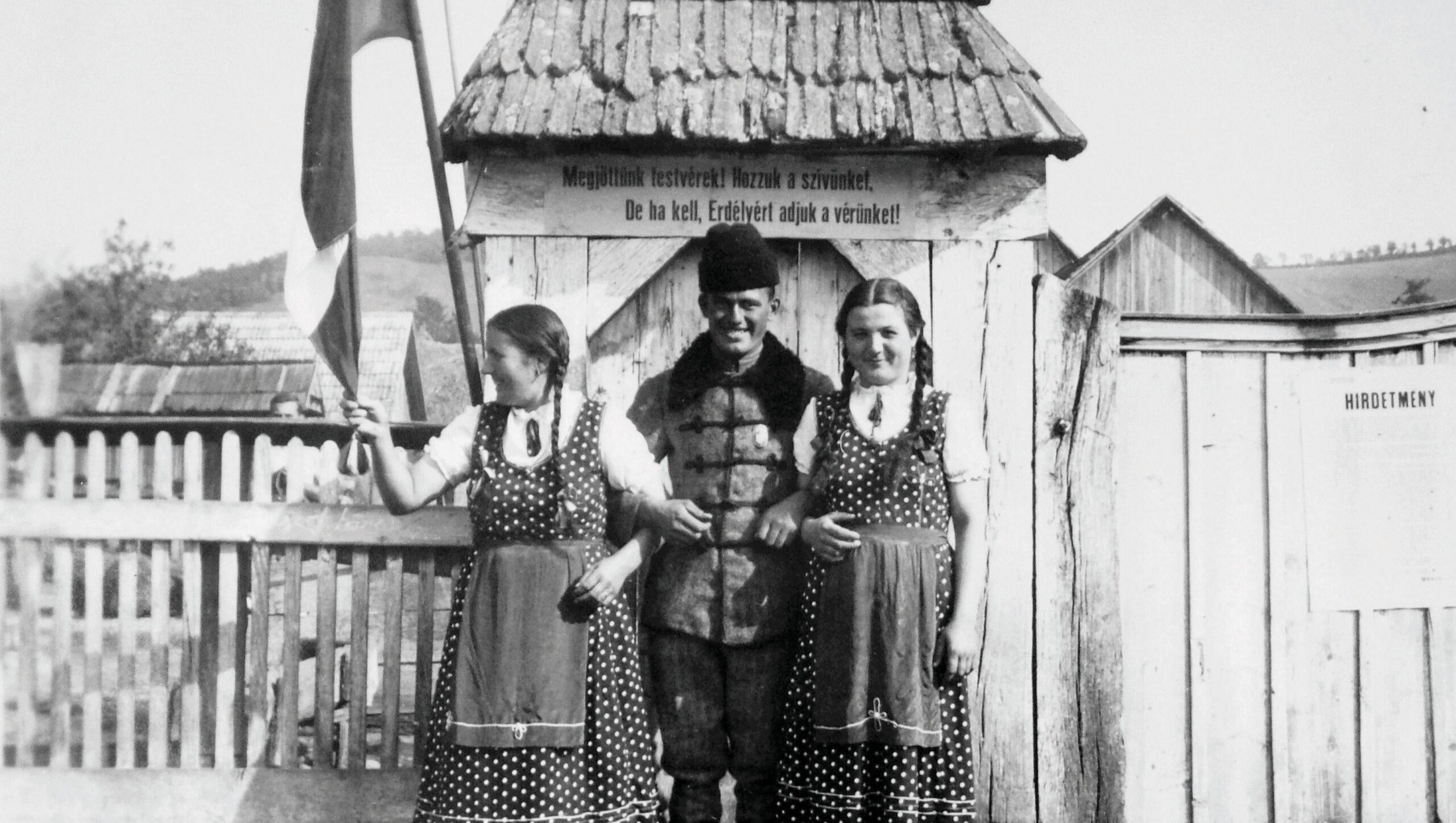

The situation of national and ethnic minorities, particularly Hungarians living beyond the borders of Hungary, is a significant topic in Hungarian public discourse and a crucial factor that influences Hungarian politics, especially foreign policy. Currently, nearly two million ethnic Hungarians live in countries neighbouring Hungary, for whom the Hungarian government ‘shall bear responsibility’ according to the Fundamental Law.1

Hungarians living as minorities often face discrimination, both individually and collectively, in their respective countries. In the cases of such violations, the Hungarian public often expects international assistance or some form of international guarantee to ensure that Hungarians abroad are not subject to discrimination in their homeland. Therefore, it is important to continuously monitor the political factors affecting the international protection of national and ethnic minorities, as these significantly impact how the legitimate interests of national and ethnic minorities, including Hungarians abroad, are represented in international professional and political discourse.

2024 — Not a Good Year for National and Ethnic Minorities?

2023 was not a good year for national and ethnic minorities, and 2024 is unlikely to be either.2 While there were numerous advances during the 1990s, in recent years we have witnessed a clear regression in this field. In Europe, more and more states are removing provisions from their legal systems that guarantee the preservation of minority identities, while international organizations are also reluctant to address the matter. The European Court of Human Rights, in its judgment of 14 September 2023 in the case of Valiullina and Others v. Latvia,3 underlined that there was no European consensus with respect to minorities’ rights in the field of education.

This process has been significantly accelerated by the ongoing transformation of the world order and the Russia–Ukraine War. In recent years, we have observed the ‘securitization’ of the situation of national and ethnic minorities. Security considerations have entered the professional discourse on minorities, and political actors are increasingly portraying minorities as security risks, sidelining the human rights aspect of the issue. This trend has been reinforced by Russia, and in particular its aggression against Ukraine, which the Russian leadership justified by claiming that it is acting to protect the Russian-speaking minority in Ukraine. This obviously false argument has provided an opportunity for various political forces to present minorities as a cause of instability. Since February 2022, numerous regional actors have exploited the crisis of our world order to abruptly resolve longstanding minority issues. A notable example is Nagorno-Karabakh, where Azerbaijan militarily ended a decades-long ethnic conflict in a few days in 2023, effectively carrying out ethnic cleansing by expelling the local Armenian population from the area.4

For Hungarians living outside Hungary, this is an unfavourable development, as Hungarian minorities continue to pursue their legitimate interests through peaceful means, using the force of law, as they have done in the past, and they definitely do not pose a security threat to their respective states. Therefore, any trend that frames the minority issue in security rather than human-rights terms is decidedly disadvantageous for them.

What can be expected in 2024 regarding the protection of national and ethnic minorities in Europe within this regional and global political framework? In short, not much good. The European Union categorically refuses to becoming involved in the issue, as evidenced by the 2021 rejection of the Minority SafePack Initiative.5 Several member states firmly oppose elevating the protection of national and ethnic minorities to the EU level, making it unlikely that any consensus will be reached on extending the EU’s competencies and duties in this area. Even though the European Parliament has consistently supported the protection of minorities,6 the European Commission and member-state governments have obstructed progress on the issue.

What can be expected in the Carpathian Basin? Parliamentary elections were held last year in Slovakia and Serbia—with results that were disappointing for Hungarians in the former case and successful in the latter. The Alliance of Hungarians in Vojvodina strengthened its position in the Serbian Parliament,7 but the Hungarian Alliance was not able to reach the parliamentary threshold and thus could not return to the Slovak Parliament.8 Moreover, in June 2024, the Hungarian Alliance did not reach the threshold at the European elections, either. In Romania, 2024 will be a super election year, with four elections posing a challenge for the Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania. The first round was a success; the party secured two seats in the European Parliament (see more on this in section three below). Ukraine remains in the most difficult situation; besides the horrors of war, the minority rights of Transcarpathian Hungarians cannot be considered settled yet, even with the legal amendments adopted in December 2023.9

There has indeed been a regression in terms of protection of national and ethnic minority rights in the political sphere, which compels minority rights advocates to intensify their legal advocacy activities. Legal actions before the courts are less affected by the current negative (geo)political developments. Minority rights advocates should submit as many individual claims to international judicial and quasi-judicial bodies, more specifically the European Court of Human Rights and the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, as possible. Even though such cases focus on the violations of individual human rights of persons belonging to ethnic and national minorities, the merits of the case focus on issues that affect the whole minority. Therefore, in the event of positive decisions at these international fora, the respective states are forced to change the challenged legal framework or legal practice, which may result in modifying the national legal framework in a way that is beneficial to the minority community. This strategy currently offers the greatest potential for improving the legal situation of Hungarians abroad. For Hungarians outside Hungary, the law remains their strongest weapon; they cannot lose faith in the power of the law, despite the current political setbacks and narrowing opportunities.

European Elections

The European Parliament elections were held this year between 6 and 9 June. Although the Hungarian minorities in Slovakia and Romania face different challenges, their aim in the election was the same: to secure seats in the European Parliament so that they would not remain unrepresented.10

In Romania, for the first time, the European and local elections were held on the same day, 9 June. This day marked the beginning of an election-heavy six months: a two-round presidential election is expected in September, followed by parliamentary elections in December. This joint election posed a significant challenge for the Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania (DAHR) because the typically high turnout in local elections increased interest in the European election among the Romanian majority. It was clear before the vote that the election’s outcome would influence the Hungarian ethnic community’s voting enthusiasm for the subsequent three elections; success could provide motivation, while failure might dampen enthusiasm for the rest of the year. Another challenge was the 5-per-cent threshold for entry: in 2019, DAHR barely crossed it with 5.26 per cent, but the demographic situation and trust in the EU have only worsened in the last five years.

Hungarian voters in Romania overwhelmingly support Hungarian parties. The concentration of votes was aided by the fact that the smaller ethnic Hungarian parties in Romania also ran on the DAHR election list, preventing the Hungarian votes from being split.

The election results were favourable for Hungarians: DAHR received 6.63 per cent of the vote,11 maintaining its two seats in the European Parliament. Gyula Winkler and Loránt Vincze will represent Transylvanian Hungarians for the next five years in Strasbourg.

This outcome is a significant success for the DAHR and Transylvanian Hungarian politics, especially considering that the Hungarian population in Romania is approximately 6 per cent of the country’s total population based on the 2021 census, yet DAHR secured 6.63 per cent of the vote on 9 June. This indicates stable support for the Hungarian party among Transylvanian Hungarians and effective voter mobilization by the party. Transylvanian Hungarian politicians can approach the autumn elections, particularly the parliamentary elections, with optimism. If the latter also yields positive results, the political representation of Transylvanian Hungarians could solidify its position in Romanian domestic politics for years to come.

In Slovakia, the European election was held on 8 June, marking the end of an election-heavy year: a snap parliamentary election was held on 30 September 2023, followed by a two-round presidential election on 23 March and 6 April. The Hungarian Alliance, the political party of ethnic Hungarians in Slovakia, faced a crucial election after a period of setbacks: the ethnic Hungarian party has not been represented in the Slovak Parliament since 2010, nor in the European Parliament since 2019. The party also failed to meet the threshold in last year’s elections.12 Nor was the presidential election a success for the Hungarian minority: Krisztián Forró, the presidential candidate nominated by the Hungarian Alliance, which claims to represent Hungarians in Slovakia, 8 per cent of the country’s total population, only secured 2.9 per cent of the vote.13

Hungarian politics in Slovakia faced complex challenges: voter turnout is consistently low in the southern areas where ethnic Hungarians live, and unlike in Romania, Hungarian participation in elections does not automatically translate to votes for Hungarian parties. In the last parliamentary election, about half of ethnic Hungarian voters in Slovakia voted for Slovak parties.

Five years ago, the Party of the Hungarian Community in Slovakia narrowly missed a seat in the European Parliament as it secured only 4.96 per cent of the vote, falling short by just 400 votes. At that time, Hungarian votes were split between the ethnic-Hungarian Party of the Hungarian Community in Slovakia and the interethnic Most-Híd Party. Now, with no such division, the Hungarian Alliance was the only ethnic Hungarian party on the political spectrum. Until 2019, Slovakian Hungarians always had two representatives in Brussels.

This election resulted in another significant setback for Slovakian Hungarian politics and the Hungarian Alliance: the party failed to secure a mandate, obtaining only 3.9 per cent of the vote.14 This failure means that the Slovakian Hungarians will lack representation in the European Parliament for the second consecutive term.

The Hungarian Alliance fought for its survival and the political unity it created. It was apparent before the election that failure could bring about the end of ethnically organized Hungarian politics in Slovakia, at least in terms of national elections, meaning that Hungarian parties might no longer run independently in national elections (regionally the Hungarian Alliance is still strong, but continually fails to reach the 5-per-cent national threshold). The coming months will reveal the future direction of Hungarian politics in Slovakia.

Sovereigntists VS Minority Rights Advocates in the European Parliament

The protection of national and ethnic minorities and the advancement of the legal and political situation of Hungarians living abroad are key tasks for the Hungarian representatives in the European Parliament. Therefore, it is crucial to examine the broader opportunities that European Parliamentary politics provide for advocating minority interests.15

The 2024 European Parliamentary elections resulted in the strengthening of the right-wing political parties. However, this is unlikely to lead to a significant political realignment in the European Parliament. The largest number of seats was won by the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP). Although the Socialists (S&D) and Liberals (Renew) weakened significantly, the three groups combined still hold a majority.16 The right-wing parties (European Conservatives and Reformists, or ECR, and Identity and Democracy, or ID) were not able to form a large right-wing bloc due to their irreconcilable differences and the EPP’s refusal to cooperate with the radical right.

The significance of sovereigntist and Eurosceptic forces may increase in the near term. However, this does not necessarily bode well for national and ethnic minorities, since in the previous parliamentary term, ECR and ID members were firmly against EU-level protection of minorities. A notable example is the vote on the resolution on the Minority SafePack Initiative in the European Parliament in 2020.17 Left-wing and liberal groups, as well as the majority of the EPP, supported the proposal (with some exceptions from Romanian, Spanish, French, and Slovak MEPs), while the majority of ID and ECR members opposed it, including representatives from the Polish Law and Justice Party (ECR), the Brothers of Italy (ECR), the Spanish Vox (ECR), the French National Rally (ID), the German Alternative for Germany (ID), the Freedom Party of Austria (ID), and the Flemish Interest–Vlaams Belang (ID). Only Fidesz and the Italian Lega from the radical right supported the proposal (it is worth noting that Matteo Salvini’s Lega is one of the biggest losers of this years’ European elections, dropping from 23 seats to just 8).

A similar situation occurred in 2023 with Lóránt Vincze’s report on institutional relations between the EU and the Council of Europe and the promotion of EU-level minority protection.18 The left-wing and centrist parties supported the proposal, while the ECR and ID opposed it or abstained.19

‘While Hungarians interpret the issue of national and ethnic minorities primarily from the perspective of national and cultural identity, in the United States, the matter is primarily seen from a security perspective’

In July 2024, the political right in the European Parliament was reorganized, and as a result, the Patriots for Europe group was created as the third-largest party group in the European Parliament,20 which merits separate examination from the perspective of minority protection. The group will include Fidesz and Lega, both of which supported proposals to enhance EU minority protection in the previous term, as well as the Czech ANO 2011, which was then part of the liberal Renew faction. However, the group also includes parties that consistently voted against minority protection proposals, including the National Rally, the Freedom Party of Austria, Flemish Interest–Vlaams Belang, and Vox (the Dutch Party for Freedom is also a relevant member of this group, but they did not have representation in the European Parliament in the previous term). Thus, the group predominantly comprises forces opposed to the EU-level protection of national and ethnic minorities.

We may draw the conclusion that radical right-wing parties that champion national sovereignty typically oppose EU-level protection for national and ethnic minorities, with a few exceptions. There are domestic political reasons for this stance, as these parties do not prioritize the issue at home. This phenomenon also suggests that the sovereigntist ideology is somewhat at odds with the notion of the EU giving special attention to minority issues.

A more significant reason might be that the protection of national minority rights is based on the human rights narrative, which can be seen as a limitation on national sovereignty. The human rights concept posits that individuals have inalienable rights that states must not violate, necessitating international guarantees. The protection of national and ethnic minorities also has a community aspect, aimed at preserving group characteristics and regional cultures, including those of national and ethnic minorities. This aspect, which goes beyond the human rights concept, is conservative in nature, yet European conservatives do not generally embrace it.

The political landscape regarding minority protection is largely shaped by the human rights approach, leading to the idea that the rights of national and ethnic minorities require EU-level guarantees. Without it, individual states can and do infringe upon these rights, as seen in the Baltic states.

The protection of national and ethnic minorities is a highly sensitive issue, which results in the EU having no explicit competence in this area (although this does not mean the EU can do nothing). When certain political forces advocate for strengthening EU-level minority protection, sovereigntist forces argue that this constitutes an illegal infringement of member states’ competences (as Romania and Slovakia have long argued against Hungarian-inspired proposals in the EU).

The EU-level protection of national minorities is a key task for all Hungarian political representatives, and can also be seen as a constitutional obligation. Hungary is the foremost European advocate for EU-level guarantees for national minorities, as portrayed in its political advocacy regarding minority rights in Ukraine.21 However, there is a contradiction between Hungary’s kin-state policy goals and the government’s sovereigntist orientation, which poses significant challenges for the Hungarian political right. Kin-state policy goals do limit Hungarian foreign policy, just as human rights limit national sovereignty.

The confrontation between a sovereigntist approach and the pursuit of EU-level minority protection in the European Parliament should be addressed in the upcoming parliamentary cycle. The Hungarian political right has a responsibility to find the right balance in this and to ensure that EU-level minority protection is not trapped by European sovereigntist tendencies. This is particularly true at a time when the voice of the European right seems to be growing louder. At the same time, the realities of European politics also manifested in the European Parliament, cannot be ignored.

The 2024 Hungarian EU Presidency and the Protection of National and Ethnic Minorities

On 1 July 2024, Hungary took over the six-month rotating presidency of the Council of the European Union.22 Many have overly optimistic expectations for this period, anticipating an intense presentation of issues important to Hungary during the term. Generally speaking, one such key issue is the EU-level protection of national and ethnic minorities. However, there is little chance that this specific topic will become decisive during Hungary’s EU presidency.23

When I asked my university students what they think the Hungarian government should focus on during the Hungarian presidency of the Council of the EU, a significant number mentioned the protection of national and ethnic minorities. They did so because they deemed the situation of minorities, especially the injustices faced by Hungarians living beyond the borders, as unfair, and expected the EU to provide a solution.

The reasoning is not unfounded: the protection of national minorities has always been a cornerstone of Hungarian foreign policy. In recent decades, various Hungarian governments have repeatedly proposed extending EU-level protection for national and ethnic minorities. In recent years, several initiatives have been launched advocating for the creation of an EU guarantee system. The protection of national minorities was the top priority of the 2021 Hungarian presidency of the Council of Europe.24 While the main tasks of the Council of Europe are the protection of democracy, the rule of law, and human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities, the EU’s ability to act in this field is much more limited. Although protecting the rights of persons belonging to minorities is a fundamental value of the EU, the Union does not have explicit competence in this regard.

A comprehensive solution would require amending the EU Treaties to include the matter among the EU competences, which is currently not politically feasible. While the Treaties do not preclude the adoption of EU legislation that would aim to increase the protection of persons belonging to national and linguistic minorities and to support the Union’s cultural and linguistic diversity,25 the European Commission has refrained from doing so. Furthermore, several member states, including France, Greece, and the Baltic states, as well as Romania and Slovakia, reject the idea of EU-level minority protection.

In recent years, Hungary has actively opposed illegal intrusion into member states’ competences. Thus, if the Hungarian government were to propose initiatives that were too forward-looking in minority protection, it could incur the displeasure of its sovereigntist allies. Most European sovereigntist parties oppose EU-level protection of national minorities, as discussed in the previous chapter, and the abovementioned contradiction between Hungarian sovereigntist foreign policy and its kin-state policy motivated desire for EU-level minority protection will not be resolved during the Hungarian EU Presidency.

Furthermore, the rotating presidency of the EU Council is inherently ill-suited for use as a tool to enforce the interests of a given member state. The rotating president must act as a neutral and impartial intermediary, an ‘honest broker’, and although this does not mean they have no room to highlight important issues for the member state holding the presidency, this is less true for divisive topics such as the protection of national and ethnic minorities.

Another difficulty is that the renewal of EU institutions following the European elections, including the election process of the new European Commission, will occur during the Hungarian presidency. The European Parliament, the co-legislator of the EU, will be preoccupied with this process for the greater part of the Hungarian presidency, which is a significant limitation.

This does not mean, however, that the Hungarian government, known as an advocate for the protection of national minorities, cannot present the issue in some form in the second half of 2024. The presidency presents an opportunity to highlight important issues not only in traditional political and policy forums but also at cultural, academic, and community events. It would be useful to organize background discussions and scholarly events to facilitate a better understanding of Hungarian kin-state policy goals, and provide deeper insight into the arguments for why EU-level expectations in this area should be increased.

The official event calendar of the Hungarian EU presidency shows that on 7 and 8 November a two-day-long international conference on the situation of national minorities will be held.26 This event provides an opportunity to present a matter important to Hungary within a scholarly and professional discourse, taking advantage of the attention directed at the presidency. However, it also indicates that the Hungarian government is not likely to define a higher goal in this area for the presidential term, probably for the reasons outlined above.

The political discourse on the EU-level protection of national and ethnic minorities will not reach a turning point during the Hungarian EU presidency. However, it is important that the Hungarian government, acting as an honest broker, with the cooperation of civil society and academic actors, facilitate dialogue and policy cooperation among interested political actors.

Minority Rights Advocacy in the United States

The key event of 2024, undoubtedly affecting European politics, but much less so the situation of national and ethnic minorities, is the US presidential election. Although minority protection is not at all part of the discourse surrounding the presidential election, still less the situation of Hungarian communities beyond the borders, the presidential race encourages us to reiterate the importance of the United States in advocating for minority rights.27

In early December 2023, Chairman Hunor Kelemen and MEP Loránt Vincze of DAHR travelled to the US to inform American foreign policy decision-makers and members of Congress about the situation of Hungarians in Romania.28 Two weeks later, János Fiala-Butora, a human rights expert from Slovakia, visited Washington with the author of this paper to deliver a presentation at a workshop organized by Freedom and Identity in Central Europe to provide information on human rights abuses against Hungarians beyond the borders, the situation of Hungarians in Slovakia, and the ongoing enforcement of the Beneš Decrees.29

Informing American foreign policy influencers and decision-makers interested in Central Europe about human and minority rights abuses against Hungarian minorities in the region is a decades-old tradition in Washington. The American commitment to promoting global human rights after the Second World War motivated peoples around the world to inform Washington—primarily understood as the interdependent and complex system of governmental and non-governmental organizations involved in foreign policy decision-making—about grievances affecting their ethnic communities, in the hope that the United States would act against the offending state and pressure it to remedy the violations. The Hungarian Human Rights Foundation and several other Hungarian–American organizations have also been active in this field since 1976.30 Hungarian human rights advocacy in the US has until now primarily focused on exposing human rights abuses against Hungarians beyond the borders since the 1970s.

While Hungarians interpret the issue of national and ethnic minorities primarily from the perspective of national and cultural identity, in the United States, the matter is primarily seen from a security perspective. This is especially understandable considering current geopolitical developments. Russia unjustly uses the protection of Russian-speaking people as a pretext to justify its expansionist military operations, currently in Ukraine. Ethnic tensions are also escalating in Kosovo, and ethnic cleansing is ongoing in Nagorno-Karabakh.

The foundation of the security policy interpretation is that unresolved minority issues lead to further complications, which can also pose problems for the United States. In the Carpathian Basin, however, the minority issue typically appears without any attendant security policy risk. This, of course, does not mean that we have no business in Washington; we just need to frame our issues differently. It is crucial to engage with our American partners in solving these problems, explaining why the issue is important to the United States. In the case of the Beneš Decrees, people in Slovakia are being deprived of their private property rights on an ethnic basis, while impediments to church restitution in Romania are a violation of religious freedom. Regarding Ukraine, it is necessary to justify the importance of Hungarian language education. Although the significance of this is less clear in the US, it is essential to emphasize that the legitimate Ukrainian nation-building aspirations based on rightful interests cannot be achieved through the suppression of national identities that have been present in the region for a thousand years, because this undermines otherwise legitimate Ukrainian nation-building intentions.

While Washington seemingly has difficulty understanding the national minority issue, Hungarian minority advocacy organizations still invest considerable efforts in informing American foreign policy decision-makers about human rights violations against Hungarians beyond the borders. To help explain this, we may recall the words of Csaba Lőrincz, one of the most important strategists of Hungarian kin-state policy, from nearly thirty years ago: ‘In geopolitics even a flick of a great power can have the effect of a punch when it reaches Hungary, Romania, or Slovakia. Even though we cannot influence the direction of punches of great powers in the geopolitical arena, we can possibly influence the direction of their flicks.’31

Advocates for the protection of national and ethnic minorities focus on these well-targeted ‘flicks’ in Washington, which can influence political decisions in relation to the rights of national minorities with the effect of a ‘punch’ in Slovakia and Romania regarding minority issues.32

While we may have doubts about whether the United States will ultimately act on issues important to us, human rights advocacy in the West in relation to the violation of the rights of national and ethnic minorities is the only route open to the advocates of minority ethnic Hungarian communities. Power politics is not good for minorities, as historical and contemporary experience shows. Minority advocacy must be placed in the discourse of human rights. Persistent, credible, and consistent work will lead to success in these efforts.

The author regularly writes opinion pieces on this topic in the ‘Lugas’ section of the Hungarian daily newspaper, Magyar Nemzet. This article is a revised, updated, and consolidated version of these selected writings.

NOTES

1 ‘Article D of The Fundamental Law of Hungary, 2011’, Ministry of Justice (2021), www.parlament.hu/documents/125505/138409/Fundamental+law/73811993-c377-428d-9808-ee03d6fb8178, accessed 6 July 2024.

2 See the updated and edited English version of the op- ed by Balázs Tárnok, ‘Nem a nemzeti kisebbségek éve volt 2023, az idei sem lesz az’ (2023 Was Not a Good Year for National Minorities, and This Year Is Unlikely to Be Either), Magyar Nemzet (9 January 2024), https://magyarnemzet.hu/lugas-rovat/2024/01/tarnok-balazs-nem-a-nemzeti-kisebbsegek-eve-volt-2023-az-idei-sem-lesz-az, accessed 6 July 2024.

3 European Court of Human Rights, ‘Valiullina and Others v. Latvia 56928/19, 7306/20, and 11937/20. Judgment 14.9.2023 [Section V]’, 14 September 2023, https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#{%22itemid%22:[%22002-14185%22]}, accessed 6 July 2024.

4 David J. Scheffer, ‘Ethnic Cleansing Is Happening in Nagorno-Karabakh. How Can the World Respond?’, Council on Foreign Relations (4 October 2023), www.cfr.org/article/ethnic-cleansing-happening-nagorno- karabakh-how-can-world-respond, accessed 6 July 2024.

5 Balázs Tárnok, ‘The European Commission Turned Its Back on National and Linguistic Minorities’, Europe Strategy Research Institute (20 January 2021), https://eustrat.uni-nke.hu/hirek/2021/01/20/the-european-commission-turned-its-back-on-national-and-linguistic-minorities, accessed 6 July 2024.

6 Noémi Nagy, and Balázs Vizi, ‘The European Parliament, the Council and the European Council’, in Tove H. Malloy, and Balázs Vizi, eds, Research Handbook on Minority Politics in the European Union (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2022), 128–143.

7 Zsolt Péter Szabó, ‘Serbian Elections: Hungarians in Vojvodina Have Reason to Celebrate’, Magyar Nemzet (19 December 2023), https://magyarnemzet.hu/english/2023/12/serbian-elections-hungarians-in-vojvodina-have-reason-to-celebrate, accessed 6 July 2024.

8 Patrik Szicherle, ‘What Is the Path forward for Slovakia’s Hungarians?’, Globsec (24 October 2023), www.globsec.org/sites/default/files/2023-10/What%20is%20the%20path%20forward%20for%20Slovakia’s%20 Hungarians_v2.pdf, accessed 6 July 2024.

9 Marcin Jędrysiak, and Krzysztof Nieczypor, ‘Ukraine: Another Amendment to the Law on National Minorities’, OSW Centre for Eastern Studies (13 December 2023), www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2023-12-13/ukraine-another-amendment-to-law-national-minorities, accessed 6 July 2024.

10 See the updated and edited English version of the op-ed by Balázs Tárnok, ‘EP-választás határon túl’ (European Elections beyond the Borders), Magyar Nemzet (1 May 2024), https://magyarnemzet.hu/lugas-rovat/2024/05/tarnok-balazs-ep-valasztas-hataron-tul, accessed 6 July 2024.

11 ‘2024 European Election Results – Romania’, https://results.elections.europa.eu/en/romania/, accessed 6 July 2024.

12 Szicherle, ‘What Is the Path forward for Slovakia’s Hungarians?’

13 ‘Leader of Slovakian Hungarian Alliance Reflects on Presidential Election’, Hungary Today (25 March 2024), https://hungarytoday.hu/leader-of-the-slovakian-hungarian-alliance-reflects-on-presidential-election/, accessed 6 July 2024.

14 ‘2024 European Election Results – Slovakia’, https://results.elections.europa.eu/en/slovakia/, accessed 6 July 2024.

15 See the updated and edited English version of the op-ed by Balázs Tárnok, ‘Szuverenisták és kisebbségi jogok az EP-ben’ (Sovereigntists and Minority Rights in the European Parliament), Magyar Nemzet (26 June 2024), https://magyarnemzet.hu/lugas-rovat/2024/06/tarnok-balazs-szuverenistak-es-kisebbsegi-jogok-az-ep-ben, accessed 6 July 2024.

16 ‘2024 European Election Results’, https://results. elections.europa.eu/en/, accessed 6 July 2024.

17 ‘European Parliament Resolution of 17 December 2020 on the European Citizens’ Initiative “Minority SafePack – one million signatures for diversity in Europe”’ (2020/2846(RSP)), www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2020-0370_EN.html accessed 7 July 2024; ‘European Parliament – Results of Votes, 17 December 2020 (B9-0403/2020)’, www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/PV-9-2020-12-17-RCV_HU.pdf?fbclid=IwAR27GY7eIU34Rx9qFcXKNMC_L-icx2ul5XAXtwKvxk-D1OvGo4HglnTZvhM, accessed 7 July 2024.

18 ‘European Parliament Resolution of 18 April 2023 on the Institutional Relations between the EU and the Council of Europe (2022/2137(INI))’, www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2023-0103_EN.html, accessed 7 July 2024.

19 ‘European Parliament – Results of Votes, 18 April 2023’, www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/PV-9-2023-04-18-RCV_EN.pdf, accessed 7 July 2024.

20 Gerardo Fortuna, ‘Far-right Patriots Group Springs to Third Force in European Parliament’, Euronews.com (8 July 2024), www.euronews.com/my-europe/2024/07/08/far-right-patriots-group-springs-to-third-force-in-european-parliament, accessed 8 July 2024.

21 Clara Marchaud, ‘Language Rights of Hungarian Minority in Ukraine at the Heart of Kyiv–Budapest Spat’, Euractiv.com (27 June 2024), www.euractiv.com/section/europe-s-east/news/language-rights-of-hungarian-minority-in-ukraine-at-the-heart-of-kyiv-budapest-spat/, accessed 7 July 2024.

22 See the updated and edited English version of the op-ed by Balázs Tárnok, ‘Kisebbségvédelem a magyar EU-elnökség idején’ (Protection of Minorities during the Hungarian EU Presidency), Magyar Nemzet (28 May 2024), https://magyarnemzet.hu/lugas-rovat/2024/05/tarnok-balazs-kisebbsegvedelem-a-magyar-eu-elnokseg-idejen#google_vignette, accessed 7 July 2024; also see Tibor Navracsics, and Balázs Tárnok, eds, The 2024 Hungarian EU Presidency (Ludovika), 2024.

23 Balázs Tárnok, ‘Opportunities and Challenges for the Hungarian EU Presidency in 2024 in the Field of Protection of National Minorities’, in Tibor Navracsics, Laura Schmidt, and Balázs Tárnok, eds, On the Way to the Hungarian EU Presidency: Opportunities and Challenges for the Hungarian EU Presidency in 2024 in the Field of EU Policies (Ludovika, 2023), 47–61.

24 ‘Priorities of the Hungarian Presidency of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe (21 May – 17 November 2021)’, https://search.coe.int/cm#{%22CoEIdentifier%22:[%220900001680a28829%22],%22sort%22:[%22CoEValidationDate%20Descending%22]}, accessed 7 July 2024.

25 ‘Judgment of the General Court of 24 September 2019 in Case T-391/17, Romania v European Commission, ECLI:EU:T:2019:672, InfoCuria (24 September 2019), 56, https://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf;jsessionid=3D4F19CB73CED95780FCEAEBB325B-47F?text=&docid=218121&pageIndex=0&doclang=EN&mode=lst&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=15049045, accessed 7 July 2024.

26 Hungarian Presidency of the Council of the European Union, ‘The Situation of National Minorities in the EU (International Conference)’, https://hungarian-presidency.consilium.europa.eu/en/events/the-situation-of-national-minorities-in-the-eu-international-conference/, accessed 7 July 2024.

27 See the updated and edited English version of the op-ed by Balázs Tárnok, ‘Álmainkban Amerika visszainteget’ (In Our Dreams America Waves Back), Magyar Nemzet (15 December 2023), https://magyarnemzet.hu/lugas-rovat/2023/12/tarnok-balazs-almainkban-amerika-visszainteget, accessed 7 July 2024.

28 ‘Hungarian Minority Leaders from Romania Meet with Decision-makers in Washington’, Hungarian Human Rights Foundation (7 December 2023), https://hhrf.org/hhrfnewsletter/hungarian-minority-leaders-from-romania-in-dc/, accessed 7 July 2024.

29 Balázs Tárnok, ‘Workshop on Ethnic and Religious Minority Rights in Central Europe’, FICEgroup.org (16 December 2023), https://ficegroup.org/workshop-on-ethnic-and-religious-minority-rights-in-central-europe/, accessed 7 July 2024.

30 Eszter Kovács, ‘The Power of Second-generation Diaspora: Hungarian Ethnic Lobbying in the United States in the 1970S–1980s’, Diaspora Studies, 11/2 (2018), DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2018.1554315.

31 Csaba Lőrincz, ‘Kihasználatlan külpolitikai mozgástér’ (Unexploited Room for Manoeuvre in Foreign Policy), in Csaba Lőrincz et al., Nemzetpolitika ’88–’98 (Budapest: Osiris, 1998), 232–235.

32 Balázs Tárnok, ‘Protection of the Rights and Promotion of the Interests of National Minorities in a New Era’, Hungarian Conservative, 2/6 (2022), 14–21, www.hungarianconservative.com/articles/politics/protection-of-the-rights-and-promotion-of-the-interests-of-national-minorities-in-a-new-era/, accessed 7 July 2024.