This article by Zita Meszleny was originally published in the Hungarian Chronicle in 2021.

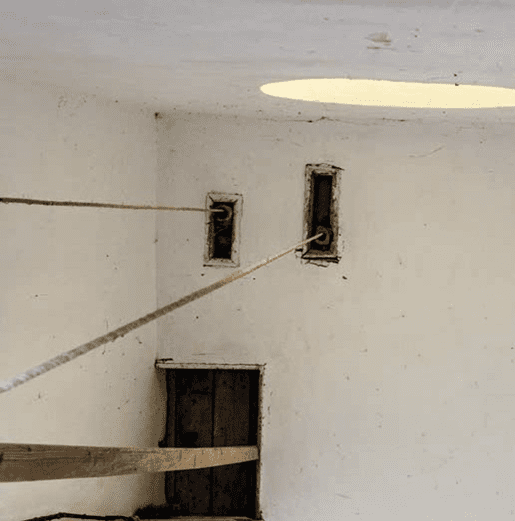

A seven-hundred-year-old church is tucked away on a gently sloping street of Terény. Its sanctum is decorated with frescos dating back to the Middle Ages, illuminated by the light seeping through the Gothic stained-glass window. The real specialty of this place, however, is not to be found on its walls.

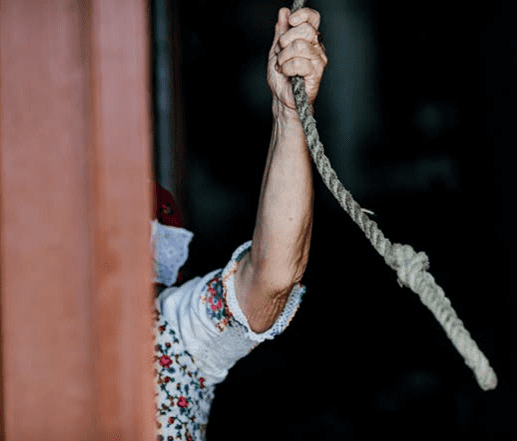

The death-knell is sounded in the tower of the church in Terény. If you know the sound, you will know that the bells are saying goodbye to someone who has passed away. It can also be discerned that Mrs Ilonka Szedlák is ringing the church bells at a steady pace in remembrance of a local man. She is one of the last few people in the country who understand and speak the language of bells.

One might say she learnt it at the same time as her mother tongue. This Palóc lady, now 77 years of age, grew up in the shadow of the church; she was born into a dynasty of bell-ringers. This service came so naturally to her that she has never asked how the task found her family. All she knows is that her great-grandfather was already calling the villagers to mass in 1870, followed by her grandfather, her father, and her mother, before she became the one who pulls the ropes in honour of the dead, or on the occasion of mass, on red-letter days, or to warn the people of the village of a fire or a storm.

Everything has its own melody, and Mrs Ilonka Szedlák always knows which of the three bells should be sounded, and how. The task is not as simple as it sounds: the three instruments are not easy to sound at the same time. When it is required, Aunt Ilonka uses her feet as well as her hands. It is also important to know how long the bells are to be sounded for. ‘While I am pulling the bell-ropes, I pray. That is how I know how long I should continue,’ the old lady says after letting go of the rope she was pulling in memory of the man who passed away.

‘A storm is different,’ she adds. It does not have its own rhythm. ‘Hail has to be scared off with the bells.’ People believe that an oncoming hailstorm is chased away by the sound of bells on its way up to the sky. People around here firmly state that they have not seen a serious hailstorm do damage to the village. So the method must be effective. This is what is also proposed by Aunt Ilonka, stealing a quick glance at the clock on the ladder of the tower.

‘I will continue to pull these ropes so long as God lets me’

It is almost noon, and today is the Feast of the Assumption. Special bell ringing is due for the occasion, and traditional folk costumes. Aunt Ilonka rushes off, to return, on short notice, in richly decorated Palóc attire. She wears it with natural pride: an animated postcard in colour, a survivor from a bygone era. But her energetic account of the items she embroidered herself brings us back to the here and now. While chatting with us, she takes up position on the stool at the foot of the church tower, next to the entrance. She adjusts her wide and bulky skirt, and falls silent. In a couple of seconds we will see what she is waiting for. The bells of the church in the next village indicate it is already noon. They are sounded a minute early there; they are automated, just like almost everywhere else. ‘Bells only live as long as they are sounded with real soul. If the soul is not in it any longer, the bells will die,’ she says, and firmly adds, ‘but I will continue to pull these ropes so long as God lets me.’ She closes her eyes, and grabs the ropes with hands and feet. The church bells of Terény start to sing.

‘I was eighteen the day before yesterday,’ Aunt Ilonka says with an ageless smile, when we ask her how old she is. She is a link between the young and the elderly, past and present, sky and earth.