By the middle of the 13th century Mongol troops had devastated large areas of the former world. Within four decades, they had reached the borders of the Latin world, including Poland, Bohemia, Hungary, and Austria. The greatest pressure was on the Kingdom of Hungary, and in 1241, after the destruction of the Hungarian royal army, they seemed unstoppable as far as Vienna and Rome. Events, however, did not continue in this direction, which surprised contemporaries. Modern historians are still searching for the answer as to why the Mongols stopped and withdrew from the Kingdom of Hungary after its conquest and, apart from later minor attacks, did not return. However, the Mongols’ campaigns in the West were part of a grand Mongol strategy, whose primary expansion was not westward, but rather to occupy the corridor between China and the Mediterranean.

Mongol rule brought not only immense destruction and suffering to the peoples of the conquered territories but also peace, known in modern research as ‘pax Mongolica’. The period of the Mongol Empire (1206–1368) is unique in world history. The most significant event of the 12th century was the foundation of the Crusader states in the Holy Land, and the 13th century saw the establishment of the Mongol Empire, the largest contiguous empire ever, covering nearly 26 million square kilometres. However, after the 1260s the Empire split into four parts: the Yuan Dynasty ruled in East Asia, the Chagatai Khanate in Central Asia, the Golden Horde in Russia, and the Ilkhanate in the Middle East. Yet the break-up of the Empire into four sub-empires was by no means the downfall of Mongol power.

The pacification of this vast territory was not only the result of the Mongols’ unrivalled superiority and mobility but also of their ability to establish and maintain imperial institutions. By controlling the Silk Road and the Volga route, and by bringing the Black Sea trade under their control, the ‘pax Mongolica’ was able to ensure relatively stable and safe travel and trade across the vast Eurasian territories.[1] This was the reason for the intercontinental journeys along the 6,500-kilometre Silk Road made by such emblematic figures of the era as the Muslim traveller Ibn Batuta and Marco Polo. The Mongol conquest of southern China also opened the door to the ‘Maritime Silk Road’, linking China along the Indian Ocean coast to the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, and the coast of Africa. Inter-regional mobility has fostered the expansion of cross-cultural exchanges in areas such as science, art, trade, and religion.[2]

Another special circumstance was that the Mongols were the first invaders from the fringes of the Christian world to integrate into Western diplomatic and ecclesiastical relations. The Catholic Church was one of the first to recognize that if the Mongols could not be defeated militarily, then an attempt must be made to integrate them into the Christian world.

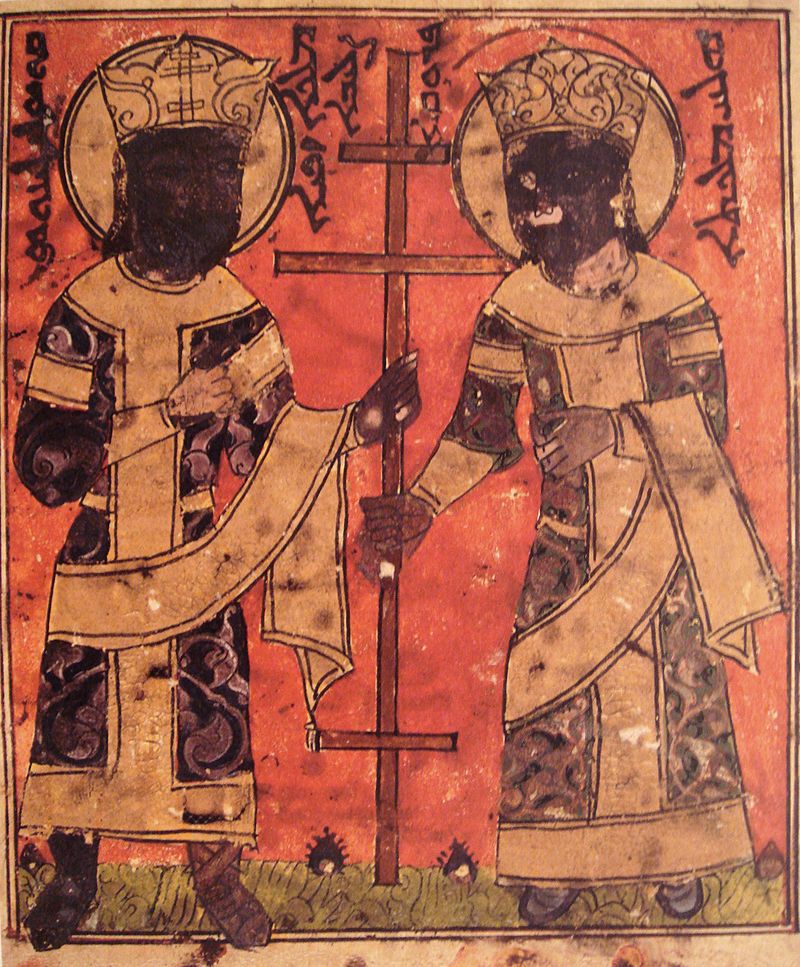

This was not at all unthinkable. On the one hand, the Mongol Empire had a long presence of Eastern Christians, especially the Nestorians and the Orthodox. On the other hand, the Mongol leadership was very tolerant of the various churches. The alliance between the Christian Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia and the Mongols could already be an encouraging example for Westerners from the 1240s. In 1307 Hayton, the famous Armenian historian and himself a member of the ruling house, read his French-language chronicle to the Pope in Poitiers, in which he advocated Mongol–Christian cooperation. In 1244, after the repeated loss of Jerusalem, Christians seriously considered the possibility of military cooperation with the Mongols in the fight against the Muslims. European rulers and the papacy received Mongol envoys and sent envoys themselves to the Mongol courts in the hope of regaining the Holy Land. To this end, the Mongol campaigns in the Middle East between 1260 and 1323, sometimes with Christian support, provided an encouraging framework, even if they remained essentially unsuccessful.[3]

‘The Mongol Empire had a long presence of Eastern Christians, especially the Nestorians and the Orthodox’

In March 1245 Pope Innocent IV sent a letter of historic importance to the Mongol court before the first Synod of Lyon began, proposing to the Khans that they accept the faith and the possibility of peace. King Louis IX of France had himself been in contact with the Mongols during his crusade from 1248. The French envoy to the Mongols reported that the Mongols were not only favourable to Christians from the East, but that there were Christians in the families of the Khan himself, and even that the mother of Güyük Khan (r. 1246–1248) was a Christian.[4] Correspondence was not without problems, of course, as the Mongols consistently stressed their claim to world domination. In 1246, for example, they wrote the following to the Pope: ‘If bearer of this petition reaches you with his own report, you, who are the great Pope, together with all the Princes, must come in person to serve us…Chinggis Khan and the Great Ögedey Khan have both transmitted the order of the Eternal God that all the world should be subordinated to the Mongols to be taken note of.’[5]

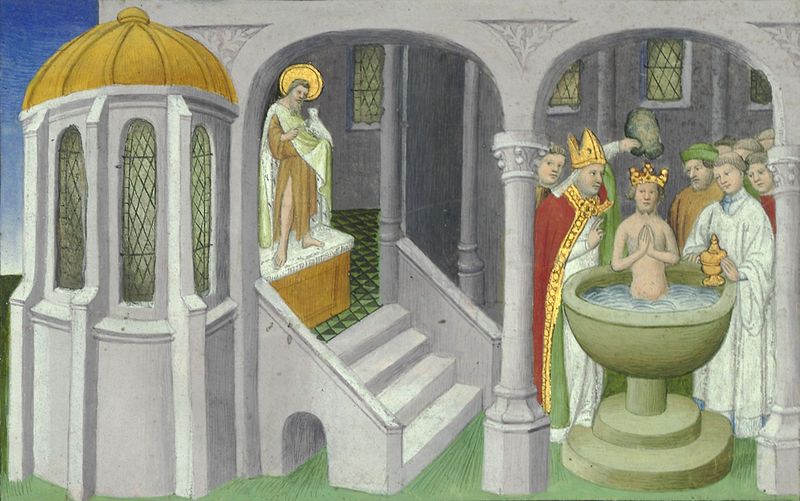

From the reign of Hulegu Khan (r. 1256–1265), however, it was the Ilkhans who were the promoters of relations, and the tone of the Mongol letters also changed, no longer demanding submission. We know that one of Hulegu’s wives was a Christian and that the wife of his son Abaqa Khan (r. 1265–1282) was the daughter of the Byzantine Emperor. Abaqa sent a large delegation to the Second Synod of Lyon, convened by the Pope in 1274, where three of their Mongol members were baptized. After a network of Christian conversion had been established in the Golden Horde and the Ilkhan Empire, missionaries also reached China after 1289. There, the Franciscan friar John of Montecorvino was appointed Archbishop of the Church of Beijing by Pope Clement V in 1307, whose jurisdiction extended to the whole Mongol world. In 1318 Pope John XXII created a Dominican-led archdiocese with the centre of Soltaniyeh in present-day Iran, which included the Ilkhanate, the Chagatai Khanate, Ethiopia, and India. The new archdiocese included Dominican bishops in Tiflis (Tbilisi, present-day Georgia), Nakhchivan (present-day Azerbaijan), Tabriz (present-day Iran), Maragheh, Samarkand (present-day Uzbekistan), and Kollam in southern India, also known as Quilon, frequented by Chinese traders. In 1362 the papacy founded another archdiocese, creating the ecclesiastical province of Sarai.

It is perhaps surprising that after the Mongol campaign in Hungary in 1241–1242, while the Hungarian court feared another Mongol invasion, Hungarian monks took an active role in the conversion of the East. There was a long tradition of conversion in Hungary, as the Hungarian Dominicans had already begun conversion among the Kumans who had moved to the Lower Danube in the 1220s, and in 1228 the bishopric of the Kumans was established, too. In the 1230s four groups of Dominicans set out in search of the Eastern Hungarians.

‘Hungarian monks took an active role in the conversion of the East’

The most famous of these was Friar Julian, who not only found the Hungarians who remained in the east but also returned from his second journey with news of the approaching Mongols and a threatening letter from Batu Khan to the Hungarian King.

After 1241 the Franciscans became the driving force for conversion. The Franciscans organized three provinces in the Mongol Empire during the 13th and 14th centuries. Conversion was particularly important in the Golden Horde, the longest-surviving Mongol Empire. Here, as a continuation of the earlier Kuman missions, the starting point for conversion was the Kingdom of Hungary. The centre of the conversion was Sarai, the capital of the Golden Horde, situated along the Lower Volga River, which was also a major trading centre visited by Italian and Armenian merchants. It is no coincidence that a missal with the feasts of the Hungarian saints survived in the Franciscan library in Assisi, Italy. Its owner is recorded as a monk from Sarai named Lazarus (‘liber fratris Lazari de Saray’).[6] The manuscript is a rare document of the participation of Hungarian monks. The Franciscan William of Rubruck reached Sarai as early as 1253, where the first record of a Franciscan monastery is dated from 1286. The presence of Hungarian converts is also attested by a letter from a Hungarian Franciscan monk, Iohanca (Iohanca Hungarus), dated 1320. In his letter, Iohanca describes that monks, mostly English, Hungarian, and German, were expected to carry out the tasks of conversion because they could learn the local language more easily. In the case of the Hungarians, this can be explained by their previous experience of the Kuman conversion in Hungary. Despite the protection offered by the Mongols, their work was not without danger. The Franciscan friar Stephanus from Várad (now Oradea, Romania), for example, was martyred in a Muslim environment, whose legend has survived. In contrast, during the reign of Özbegh Khan (r. 1313–1341) and his son Jani Beg (r. 1342–1357), a certain Elias of Hungary was a major influence in the court of the Khan of the Golden Horde, and a well-known member of the Mongol envoy to Avignon in 1340 was Elias himself.[7]

The spectacular successes were ended by the end of Mongol rule, preceded by the triumph of Islam and Buddhism in the Mongol Empire. The peace of the Mongols provided the opportunity for the movement of ideas and religions, and the end of Mongol rule meant that for a long time, there was no longer any possibility of contact with the West—the era of the first great mission of the Western Church outside Europe was over.

[1] Szilvia Kovács and Márton Vér, ‘Mongols and the Silk Roads: an Overview’, Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, Vol. 74, No. 1, 2021, pp. 1–10.

[2] Peter Jackson, The Mongols and the Islamic World: From Conquest to Conversion, New Haven-London, 2017, pp. 210–241.

[3] Peter Jackson, The Mongols and the West: 1221-1410, 2nd ed, London–New York, 2018, pp. 203–234.

[4] James D. Ryan, ‘Christian Wives of Mongol Khans: Tartar Queens and Missionary Expectations in Asia’, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 3rd Series, Vol. 8, 1998, pp. 411–421.

[5] https://ballandalus.wordpress.com/2015/06/01/mongol-papal-encounter-letter-exchange-between-pope-innocent-iv-and-guyuk-khan-in-1245-1246/, accessed 8 August 2024.

[6] László Veszprémy, ‘Egy Árpád-kori ferences kézirat Assisiben’, Ars Hungarica, Vol. 17, 1989, pp. 91–96.

[7] Szilvia Kovács, ‘Különösen angolokat, magyarokat és németeket kérünk…’: Pápák, ferencesek és az Arany Horda, Budapest, 2020, pp. 87–172.

Related articles: