The story of dissidents who emigrated from Communist Hungary is not a merry one. After 1956, more than 200,000 refugees left Hungary during the short time when the borders were open in the autumn. But before and after that, defectors risked their lives when trying to cross the border, and in fact, many were shot.

Sixty years ago, on 13 July 1956, it happened for the first time that ‘hijackers’—actually defectors—

boarded a Malév aircraft that they eventually hijacked.

Upon landing in West Germany, the seven hijackers—and two passengers who joined them—requested political asylum.

The masterminds behind the act were Ferenc Iszák—a former journalist who had become ‘completely disillusioned’ with socialism—and an ex-soldier, György Polyák, who had been dismissed from the Hungarian People’s Army due to his ‘kulak’ ancestry. The two, who both worked in the cement factory in Lábatlan as unskilled workers, and attended the local boxing club, decided they wanted to leave the country for good. They were assisted in the venture by two of Iszák’s boxing students, as well as by two amateur glider pilots that Polyák recruited. Iszák’s wife also joined them.

What prompted the hijackers to use this method of emigration? According to Mult-kor.hu, while much of the Hungarian civilian airplane fleet was destroyed during WWII, the first flight left Budaörs for Szombathely and Debrecen on 15 October 1945, and the Győr and Szeged flight was also launched in 1946. Miskolc and Pécs were soon included in the network, and in the summer of 1954, the flights, which started from Ferihegy (now called Liszt Ferenc International Airport) from 1950, already connected 11 domestic destinations with Budapest, and the price of the tickets did not exceed the first class tickets of the express train. Maszovlet ceased to exist on 25 November 1954, after the Hungarian state bought the share of the Soviet side, and was replaced by Malév, the Hungarian Aviation Company.

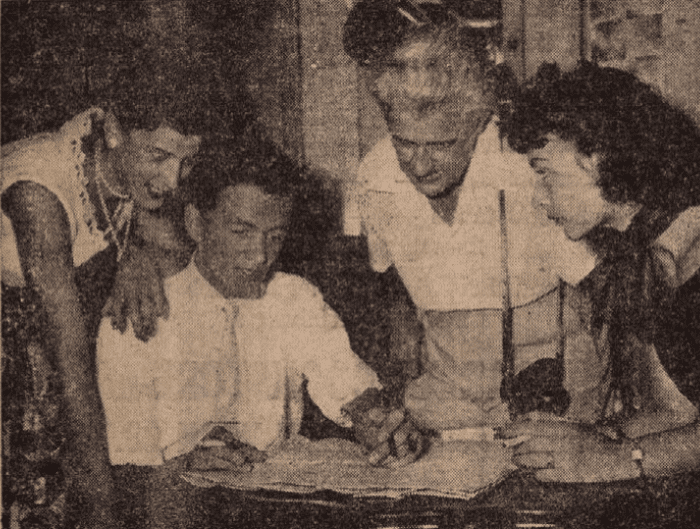

A photo of the two hijackers. PHOTO: Hungarian Conservative

Domestic air traffic was under the control of the political police, since flying was a great temptation for those looking for an opportunity to leave for the West. The political police started placing plainclothes agents on planes after a flight engineer and a pilot took control of the Pécs–Budapest flight on 4 January 1949 and flew to West Germany.

In the summer of 1956, however, it happened for the first time that prospective defectors took over a Hungarian civilian airplane with force and successfully left the country.

But what happened exactly on that day? From the recollections of the those involved, we know that the members of the team, most of whom did not know each other at all, met up at the Vörösmarty Café on the morning of 13 July 1956 and went on to the airport. There they boarded a twin-engine DC-3 plane that was headed from Budapest to Szombathely. Once near the Western border, the men started to beat the passengers into submission, believing that the plainclothes detective was among them. As it turned out, the secret police officer was in the cabin and he, for unclear reasons, never used his weapon during the scuffle. The hijackers managed to overpower all those on board and Polyák took over the piloting. He navigated the airplane at a height of 300–400 metres, thereby avoiding being detected by airspace control. The daring escapees eventually landed near Munich, after running out of fuel.

It is perhaps no surprise that

the two chief defectors were soon afterwards approached by the US military services with job offers,

which they accepted: Iszák started working for the Counter Intelligence Corps (Army CIC) while Polyák became an air force pilot, completing secret missions. Iszák later even wrote an English language book about the miraculous escape, titled Freedom Flight.

‘In spite of what was at stake, we tried to be merciful. It was my job [to beat one of the passengers], and I had a hammer with me for the action. But when I saw his face, full of dread, I had pity on him, and I decided to merely use my fists, but it was enough, as he passed out,’ Iszák recalled in an interview. The hijackers claimed to have gotten lost at a certain point. ‘We were ready for everything. We knew that if we did not succeed, death awaited us.’

Back home, the pro-Communist newspapers wrote about the ‘brutality’ of the ‘fascists’, even though it now seems clear from the sources that the hijackers were in fact disillusioned leftists. Then again, the contemporary political narrative could hardly deal with former leftist workers becoming fed up with the system and being ready to use force to leave the country.