Budapest and Warsaw commemorate the Day of Polish–Hungarian Friendship on 23 March. On this day the two nations celebrate their centuries-old good relations and cultural connectedness. It is also worth remembering, however, that Christian faith and religious institutions form a strong bond between Poland and Hungary too. The Order of Saint Paul the First Hermit, also known as Pauline Fathers and Brothers, is one example of the many religious institutions that connect the two countries. The Order, founded in Hungary, is named after Saint Paul of Thebes, the first known hermit of the Christian tradition. The Order was established in the early 13th century by Blessed Eusebius of Esztergom.

Inspired by hermits living in solitude in the mountains near Esztergom, Eusebius resigned from his position as Canon of the Cathedral of Esztergom, distributed his goods among the poor, and became a hermit himself. After years of solitude and contemplation Eusebius had a vision in which God called him to unite the hermits. Eusebius answered his call and established the Order by bringing together the hermits scattered in the Patacs Mountain and Pilis. The first friary of the Order was founded near today’s Budakeszi—the Monastery of St Lawrence at Buda (also known as the Pauline Monastery of Budaszentlőrinc) served as the monastery of the Pauline Fathers and Brothers until it was destroyed by the Ottoman Turks; today only its foundational walls can be seen. It is believed that the first Hungarian translation of the Bible (from Latin), made by László Báthory de Császár around 1456, was kept in this Pauline Monastery and went missing only once the Ottomans ransacked the Christian religious site. Albeit no original version survived from László Báthory’s translation, the Jordánszky Codex (circa 1516–1519) is believed to be a copy of the Pauline monk’s work. László Báthory’s Bible translation was an important contribution to the Hungarian language and culture. In addition, the Order played an important role in the production and preservation of medieval prayer books too, such as the Festetics and Czech Codex.

Albeit the 150 years of Ottoman rule and other political disturbances weakened the Pauline Fathers and Brothers’ presence in Hungary, the Order strengthened in other countries in Europe. Today the semi-contemplative Order is present in several countries in the continent—including Hungary, Poland, Germany, Belarus, Ukraine and Czechia—, as well as in the United States and Australia, while also having monasteries in Cameroon and South Africa. In total, the Order has 71 houses all around the world, 347 priests and 3 bishops (one in Poland, one in South Africa, and one in Australia). The headquarter of the Order today is in the Jasna Góra Monastery in Częstochowa, Poland.

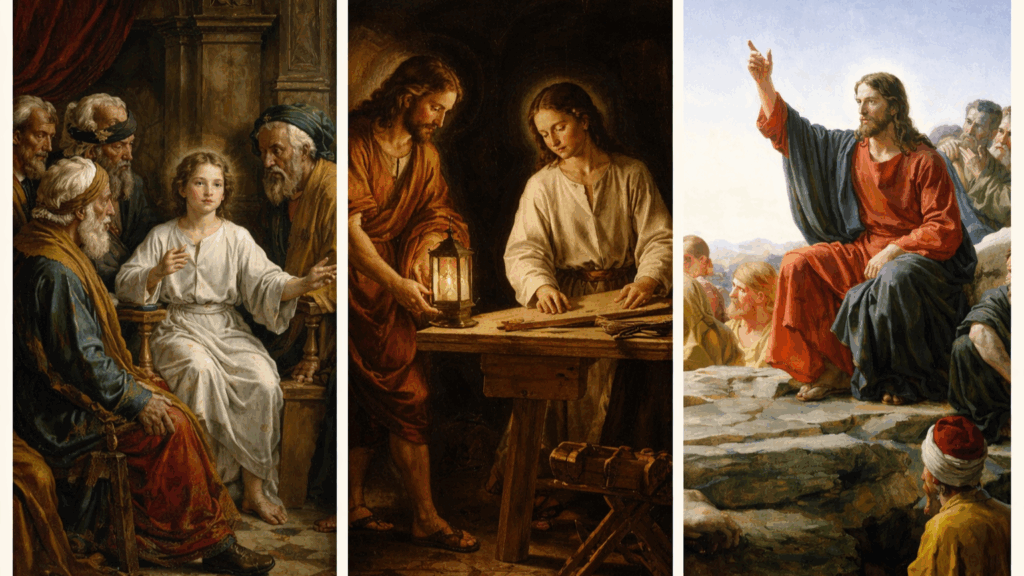

The Order is best known today for maintaining one of the world’s most important Marian shrines, the Jasna Góra Monastery in Poland. The Monastery is centred around the Our Lady of Częstochowa, an icon also known as the Black Madonna. According to historic records, in 1382 the Pauline Fathers and Brothers were entrusted with the image of Our Lady that was believed to have been painted by St Luke the Evangelist himself. The tradition holds that St Luke painted the Miraculous Image of Our Lady during the lifetime of the Blessed Virgin Mary on a board from the table used by the Holy Family in Nazareth. The Pauline monks were invited from Hungary to go to Poland with the mission of safeguarding the image as the Duke of Opole feared that pagan Tatars might desecrate it. In 1430 the Black Madonna was indeed damaged, however, not by Tatars, but in a Hussite raid. Valuable votive offerings were stolen from the chapel and the image was slashed with a sword and was broken. Albeit the image was restored—by overlaying new canvases on the existing ones—, the signs of the damage are still visible. The 1430 damage left 6 scars on the face of Mary, marks that make Our Lady of Częstochowa stand out from other representations of Virgin Mary.

After the Black Madonna was restored from the 1430 attack, the Pauline Order started to build a shrine for the venerated image in Częstochowa. In the coming centuries the city gained reputation as an important pilgrimage site and a ‘Refuge of Sinners’. Along with its growing prominence as a religious place, Jasna Góra also became known as a site of Poland’s struggle for its freedom and sovereignty. As Poland was fighting for its independence on multiple fronts, the monastery was one of few fortresses that stood against the Swedish invasion in the 17th century. After the monastery successfully survived the Swedish troops’ 40-days siege in December 1655, the Black Madonna, was praised as the saviour of the city, gained an even more widespread popularity among the Poles. Inspired by the events in Jasna Góra, a year later Mary was elected as Queen of Poland in Lviv. From this point on Jasna Góra played a crucial role in Poland’s national history as a site of freedom fights—both in a spiritual and literal sense. The 500 Jubilee of Jasna Góra in 1882 was met with Russian troops being present in the city of Częstochowa—nevertheless, nearly half million Poles gathered to mark the anniversary by praying and singing Polish songs in the Monastery. The 300th anniversary of the Lwów Oath in 1956 was similarly marked by a crowd of over a million Poles—Jasna Góra once again became a site of religious prayer for Poland’s freedom.

Today the city is home to the Order of Saint Paul the First Hermit’s largest monastery that houses over 100 Fathers and Brothers, including the Father General and the General Council. Annually more than two million pilgrims visit the Black Madonna from all over the world. On top of being an important site of Poland’s struggle for freedom, through the founders of the Monastery, the Pauline Fathers and Brothers, it is also a reminder of Poland’s connectedness to Hungary.

Related articles: