Pope Sylvester’s name is well known in Hungary, thanks to the homonymous year-end celebrations of New Year’s Eve. Of course, the Pope celebrated on 31 December (two days later in the Eastern Church) is Sylvester I. His unparalleled importance was secured by the unification of views on the person and nature of Jesus at the First Council of Nicaea, the first universal council in the history of the Church, convened in 325 AD. It was during his pontificate that Emperor Constantine I issued the Donatio Constantini, that is, the Deed of Gift of Constantine. In it, the imperial power recognized the supremacy of papal authority over the Eastern patriarchs in all matters of faith and gave the popes secular authority over Rome and the Western world. According to tradition, it was Pope Sylvester who baptized the Emperor, who had been cured of leprosy by heavenly help.

The legendary elements of the story are difficult to separate from the historical core, but it is no coincidence that the Pope of the year 1000, Sylvester II (reigned 999–1003), the French-born Gerbert d’Aurillac, chose the name of the first Pope in a symbolic decision. It is not clear either how much the apocalyptic expectations associated with the year 1000 played a part in this, but it is certain that the Pope, together with Emperor Otto III (r. 996–1002), made a conscious effort to renew the Christian world during these years.

Yet the name of Sylvester II is not preserved in historiography and folklore in connection with his reform measures, but—as a sort of ‘medieval Faust’—in connection with his collaboration with the devil. The story may be familiar to modern readers, too, since in Mikhail Bulgakov’s classic novel The Master and Margarita, Professor Woland, the black magician who plays Satan, comes to Moscow to study the manuscripts of Sylvester II. But how does this fit in with the person of a pious pope, according to contemporary sources, who followed Stoic philosophy, sought peaceful solutions, and was a supporter of science?

‘The name of Sylvester II is not preserved in historiography and folklore in connection with his reform measures, but in connection with his collaboration with the devil’

English chronicler William of Malmesbury wrote at length about the Pope in his ‘Deeds of the English Kings’, completed in 1125. He has high praise for the Pope’s studies in Hispania as a youth, but he does not condemn his underworld connections at all. He wrote:

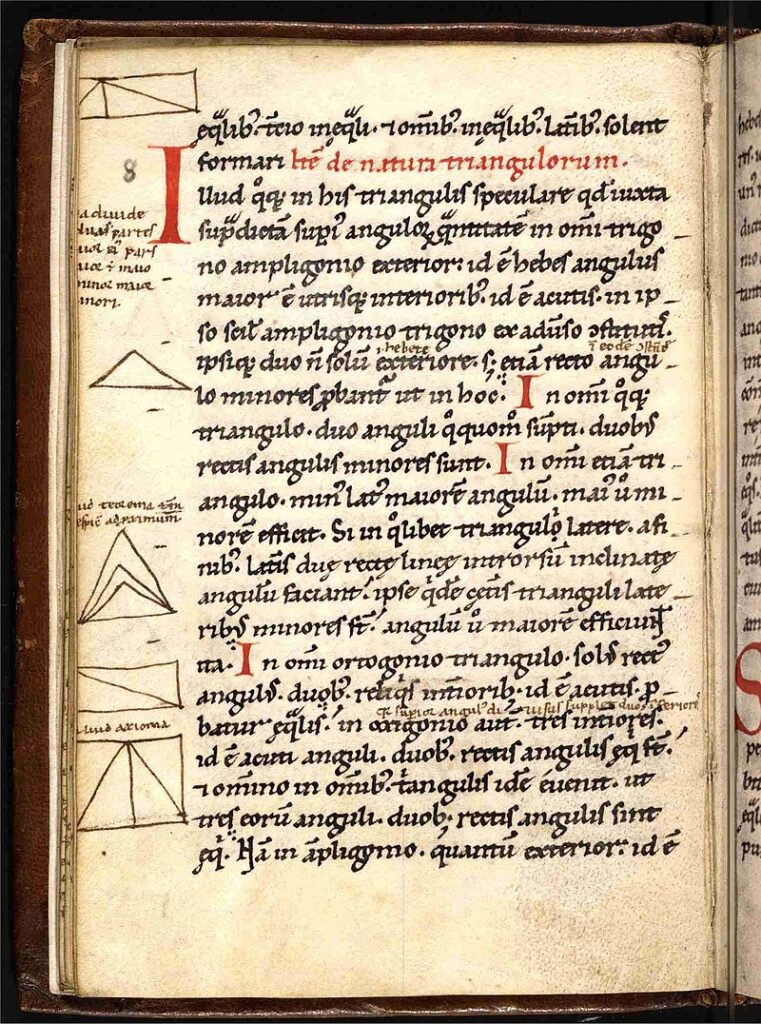

‘He conquered Ptolemy in knowledge of the astrolabe, Alhandreus in the positions of the stars, Julius Firmicus in prophesying. There he learned what the song and flight of birds portended, there he learned to summon ghostly forms from hell; there he learned everything that is either harmful or healthful that has been discovered by human curiosity; but on the permitted arts, such as arithmetic, music, and astronomy, and geometry, I need say nothing. By the way he absorbed them he made them appear beneath his ability, and through great effort he recalled to Gaul those subjects that had been long obsolete. He was truly the first to snatch the abacus from the Saracens…’

It is true, though, that William also wrote the following: ‘After a careful observation of the stars…he cast for himself the head of a statue that could speak, if questioned, and answer the truth in the affirmative or the negative.’ However, it seems that the author had no problem with this. Apparently, he also believed that the history of talking heads was a result of the instruments used for experiments, stargazing, and astrology.[1]

It is perhaps not surprising either that the memory of the Pope played a role in the investiture wars that reached their climax in the second half of the 11th century. The opposing forces fighting for the primacy of imperial and papal power were engaged in a major publicity campaign. To influence European public opinion, they prepared a series of political tracts and circulated large copies of them together with their political correspondence. The author called Benno, probably the Bishop of Osnabrück, who was active as a follower of German Emperor Henry IV, did his utmost in his writings to discredit and morally destroy the popes who opposed the Emperor. In them, the popes are portrayed, among other things, as allies of the satanic forces who had used their magical powers to destroy the Catholic Church. According to his narrative, the teachers of Pope Gregory VII, the initiator of the Gregorian Reforms, had themselves learned the devil’s arts from Gerbert, a.k.a. Sylvester II. This information was also confirmed and incorporated into the propaganda by the German Synod of Brixen in 1080. In his attack on the Pope, Benno wrote the following:

‘The wicked deeds of Gerbert included summoning a demon that he interrogated about the date of his death. The demon replied that Gerbert would not die until he said Mass in Jerusalem. Not recalling that there was a church in Rome nicknamed ‘Jerusalem’, he [Gerbert] celebrated Mass in it. Immediately after he died a horrid and miserable death, but before he begged his hands and tongue to be cut to pieces, by which having sacrificed them to demons he had dishonored God.’[2]

The Pope may indeed have died in 1003 in the church known as the Basilica of the Holy Cross in Jerusalem. Consecrated around 325, the church was dedicated to the relics of Christ, which were brought from the Holy Land with the earth from Jerusalem by Empress Helena, mother of Constantine the Great.

The fabulous story is still very popular today; one just has to look it up online. Even the authors of the medieval world chronicles were munching on the story a lot. Chronicler Sigebert of Gembloux (d. 1112) even added that ‘it is said that he died from a violent beating at the hands of the Devil…he is seen to be excluded from the number of popes’. Indeed, the opposing camp’s writers refused to call him by his papal name and referred to him until death as Gerbert.

The young Gerbert was indeed one of the most educated monks of his time, who, besides the humanities, was particularly good at natural sciences, the ‘quadrivium’ as it was called back then.[3] He must have spent years in Barcelona, Hispania, where the authority of the Frankish kings was recognized, but at the same time, the benefits of Islamic scholarship were also acknowledged. Gerbert probably did not make it to Cordova, but he did not need to as Catalonia offered him an abundance of Oriental scholarly manuscripts unavailable anywhere else in Latin Europe at the time. He later accompanied the local bishop to Rome, where his erudition impressed the Pope, who immediately recommended him to German Emperor Otto I, saying ‘that such a young man had arrived, one who had perfectly mastered astral science [mathesis] and was able to teach it to his men’.[4] He was entrusted with the education of the heir to the throne, the future Otto II, and from then until his death, he remained a supporter of the German emperors. Gerbert was a prolific author, with over 200 letters surviving, but he also wrote on astronomy, geometry, and astrolabe. His work on numbers and the abacus became a seminal work on the subject, providing an introduction to the use of Hindu Arabic numerals. He wrote about all sorts of things that were not common at the time.

‘The young Gerbert was indeed one of the most educated monks of his time, who, besides the humanities, was particularly good at natural sciences’

Otto III first wanted to place him at the head of the Church of Rheims, but then he took the Archbishopric of Ravenna. After the unexpected death of the previous German Pope in 999, the Emperor elected Gerbert to replace him. As a pope, he fought for the moral reform of the clergy, banning simony, the acquisition of ecclesiastical property for money, and concubinage. He collaborated with Otto to the greatest extent in the creation of the Emperor’s ideal of a renewed Christian Roman Empire. Their harmony is also evidenced by several documents issued both by the papal and imperial chancelleries which use similar expressions. They appeared in each other’s documents as mutual petitioners and jointly led synods. The result of their cooperation is the establishment of an independent Polish and Hungarian church organization with headquarters in Gniezno and Esztergom.

In the memory of Hungarians, the name of Sylvester II is closely linked to the coronation of St Stephen, the first Hungarian king. In 1000/1001, the Pope sent Stephen a crown due to a celestial vision, which for a long time was identified with the Holy Crown we see today. Today it is certainly known that this first crown is lost, but in medieval times there was a firm belief in their identity. Surprisingly, the authors of the legends of St Stephen did not mention the name of the Pope when they spoke of the crown, although they devoted a great deal of space to it:

‘Thus having acquired the letter of apostolic benediction together with the crown and the cross, the beloved of God, Stephen was proclaimed king and, anointed by unction with chrism, was propitiously crowned with the diadem of royal dignity while the prelates and the clergy, the counts and the commoners acclaimed him with unanimous praise.’[5]

Some suggest that this event took place around Christmas or New Year’s Day.[6] Finally, Otto’s sudden death in January 1002 brought an end to the Pope and the Emperor’s close cooperation.

The memory of Pope Sylvester is still alive and well among Hungarians. In memory of this, a relief was placed above the Pope’s tomb in the Basilica of Lateran, Rome, on the 1000th anniversary of the founding of the Kingdom of Hungary. The upper part of the relief depicts Kings St Stephen and St Ladislaus venerating the Virgin Mary and below the scene of the Pope handing the crown to Stephen’s envoy in Rome. Besides, as a belated commemoration, in 2003, Hungarian artist Gábor Szinte painted a series of historical murals for the parish church of Saint-Simon, the Pope’s home village near Aurillac, to mark the 1000th anniversary of his death.

‘In the memory of Hungarians, the name of Sylvester II is closely linked to the coronation of St Stephen, the first Hungarian king’

The epitaph of the Pope in the Basilica of Lateran immortalized the positive memory of the Pope: ‘Gerbert, born a Frenchman…became the chief shepherd of the world. He and Emperor Otto III…illuminated their age with the light of their wisdom together, the century rejoiced, and sin was destroyed…Till death came for him, for then the world was terrified, peace vanished, the victorious Church was shaken, its rest was ended.’

One of the most brilliant personalities of the 10–11th centuries fell victim to politics, only to discredit Gregory VII and the church reform. To do this, the lifework of Gerbert/Sylvester had to be ignored, and his unparalleled scientific achievements mocked and even made to look like the work of the devil.

[1] E. R. Truitt, ‘Celestial Divination and Arabic Science in Twelfth-Century England: The History of Gerbert of Aurillac’s Talking Head’, Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 73, No. 2, 2012, pp. 202–203.

[2] Truitt, ‘Celestial Divination’, p. 210.

[3] Pierre Riché, Gerbert d’Aurillac, le pape de l’an Mil, Paris, 1987.

[4] Truitt, ‘Celestial Divination’, p. 206.

[5] ‘Life of King St Stephen written by Bishop Hartvic’ (transl. by Nora Berend and Cristian Gaşpar), in Gábor Klaniczay, Ildikó Csepregi, et al. (eds.), The Sanctity of the Leaders. Holy Kings, Bishops, and Abbots from Central Europe, Eleventh to Thirteenth Centuries, Budapest, New York, Vienna, 2023, p. 131.

[6] Endre Tóth, The Hungarian Holy Crown and the Coronation Regalia, Budapest, 2021.

Related articles: