Hungarian Conservative has launched a ten-part series of articles on the past decade and a half of the Hungarian economy and society, titled ‘Revealing the Facts’. Rather than looking at a lot of different, isolated data it is worth providing an overview, comparing and analysing trends over time, in order to understand the details. In the first instalment of our series we looked at inflation. In parts two and three we highlighted that growing incomes and the security of livelihood, both of which have been experienced under the conservative governments since 2010, are of primary importance for Hungarians. The fourth analysis of the series explored the economic growth trends of the past decades. This article provides an overview of the poverty situation in Hungary.

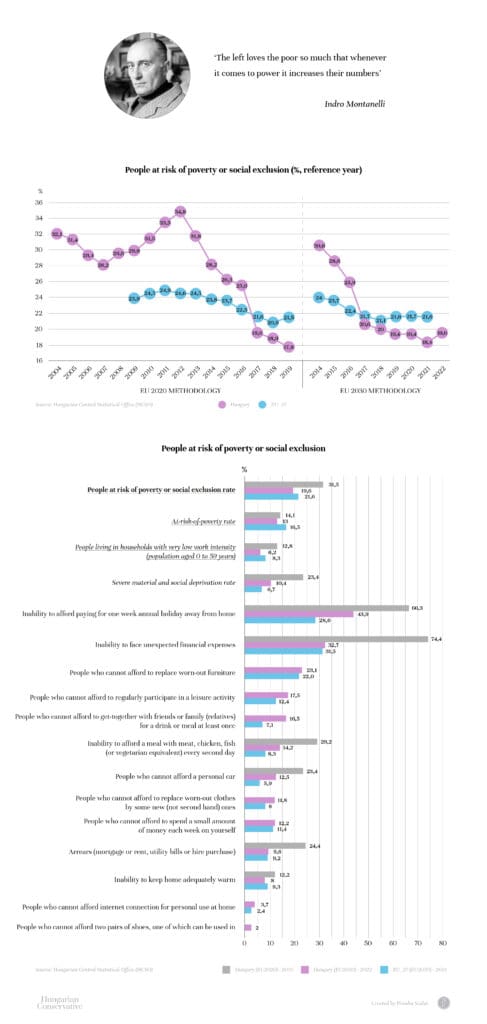

‘The left loves the poor so much that whenever it comes to power it increases their numbers,’ Italian writer and journalist Indro Montanelli (1909–2001) famously said.

Poverty reduction is a fundamental responsibility of every community. From the smallest to the national and international levels, it is everyone’s responsibility. It has therefore always been the subject of major political battles, with different political forces constructing different narratives on the issue. The dominant left proposes solutions based on aid, while the non-left proposes solutions based on work. Free money, welfare, is always more attractive, but it is unsustainable, and it is always less than what people could make if employed, thus it provides a lower standard of living and increases the proportion of people living in poverty and at risk of poverty in society.

The measurement of poverty and exclusion is also the subject of much debate. It is precisely in order to reduce these debates that the European Union has developed a standardized, modern system of indicators for the Member States, so that the living conditions of families and households, and thus the multidimensional phenomenon of poverty, could be compared at a European level. This is free from the simplifications and anomalies mentioned in our previous article.

The complex indicator consists of three sub-indicators: those at risk of poverty or social exclusion are defined as those who are affected by at least one of the three dimensions. If a household member’s net per capita income in the reference year is below 60 per cent of the median income, i.e. the poverty threshold, they are at-risk-of-poverty. Or, if household members aged 18–64 spent less than 20 per cent of their potential working hours at work, they are considered to be at risk of very low work intensity. Furthermore, those who are financially deprived in at least seven of the thirteen items in the second figure are considered to be at risk of severe material and social deprivation.

Hungary Against Poverty

The latest Eurostat data cover the reference year 2021, when

Hungary had the tenth lowest proportion of the population at risk of poverty or social exclusion, at 18.4 per cent.

This compares to 30.6 per cent in 2014, when we ranked twenty-fourth, and our improvement of 12.2 percentage points is the largest among Member States.

The measurement method has changed slightly in 2020, for example some items have been dropped and others included in the deprivation analysis, so we can only broadly compare the new data with pre–2014 data. However, the graph still shows that we have made a huge improvement on our 2010 reference year indicator of 31.5 per cent. The real improvement started when Hungary managed to repay the IMF loan in 2013 and was able to take sovereign decisions to improve the living conditions of its population, for example by starting the process of reducing taxes on labour—because the IMF demanded austerity measures for the population.

The Battle Against Child Poverty

The rate of improvement is similar for under–18s. Child poverty in Hungary has also fallen at the fastest rate among EU countries since 2010. However, it is important to note that children are never poor in their own right, but all those living in the same household are poor according to this measure, as it is a household-based measure.

In our country

we have achieved these results by expanding employment and by significantly increasing real earnings, not through family allowances.

Earnings from work are always greater than benefits and can be used to create better living conditions. Hungary has also reformed the family support system following this principle, but more on that in the next article.

The other tool of the previous liberal policy, apart from the vulnerability encouraged by the various aids, was the destruction of self-confidence and positive visions of the future, in the spirit of ‘daring to be small’ (‘merjünk kicsik lenni’ in Hungarian). In this way, it was implied that the Hungarian people could not expect a real rise in living standards. The current economic and social policy emphasizes the opposite, namely to ‘dare to be big’ (‘merjünk nagyok lenni’ in Hungarian).

Before the change of government in 2010, there was a series of ‘reform packages’, all of which involved economic austerity measures for families and the population. These included a steady raising of energy prices, a tax system that prevented real wages from rising and an employment policy that maintained unemployment.

Most of the improvement has been in the area of severe material deprivation. In 2010, three quarters of the population could not afford an unexpected expense, two thirds could not afford a week’s holiday, a quarter had mortgage arrears and a quarter could not afford a car. By comparison, the proportion of people unable to afford unexpected expenses is a third of the population and fell further in 2022, with the proportion unable to afford a week’s holiday falling to 43 per cent, those with mortgage arrears falling to around 10 per cent and those unable to afford a car falling to below 13 per cent.

HCSO has already published preliminary Hungarian data for the 2022 reference year. It can be seen that in 2021 our composite indicator and its two sub-indicators were better than the EU average. In the difficult year 2022, the poverty rate in Hungary worsened slightly, but even after the worsening it did not reach as high as the EU average of 2021. We estimate that several Member States’ indicators also worsened in 2022, but we will not know the exact extent until later.

Durable Results

It is notable that five of the 13 deprivation items still show a decrease in the proportion of people at risk in 2022: having no money for unexpected expenses, being behind on loan repayments or utility bills, not owning a car due to financial constraints, not having internet access at home due to financial constraints, not owning two pairs of shoes. It seems that the lessons learned during the currency crisis are still alive in society and people are saving and doing everything they can to avoid debt.

The improvements of the last decade are such that they have not been eroded by the recent difficult years. The Hungarian experience has led to the need to rewrite sociology textbooks in many places (it is still taught that the most effective way to reduce child poverty is through family allowances). We have shown that when parents have jobs and their incomes increase in real terms, poverty among children—and their parents—decreases much more significantly.

Piroska Szalai is a labour market expert, a researcher at Economy and Competitiveness Research Institute of the Ludovika University of Public Service.

Kristóf Nagy and Mátyás Zsolt Varga are journalists at Mandiner.

Related articles: