Hungarian Conservative has launched a ten-part series of articles on the past decade and a half of the Hungarian economy and society, titled ‘Revealing the Facts’. Rather than looking at a lot of different, isolated data it is worth providing an overview, comparing and analysing trends over time, in order to understand the details. In the first part of our series we provided an overview of the history of inflation, while in the second one we analysed the changes in employment in Hungary over the past decades. This article briefly explores the main features of real earnings growth in Hungary.

As we explained in the previous part, stable work and a secure livelihood are the most important things for Hungarians. We know that we can always live better from work than from benefits, and we can only move forward if the purchasing power and the real value of our earnings also increases, i.e. increases faster than inflation.

A Short Real Earnings History

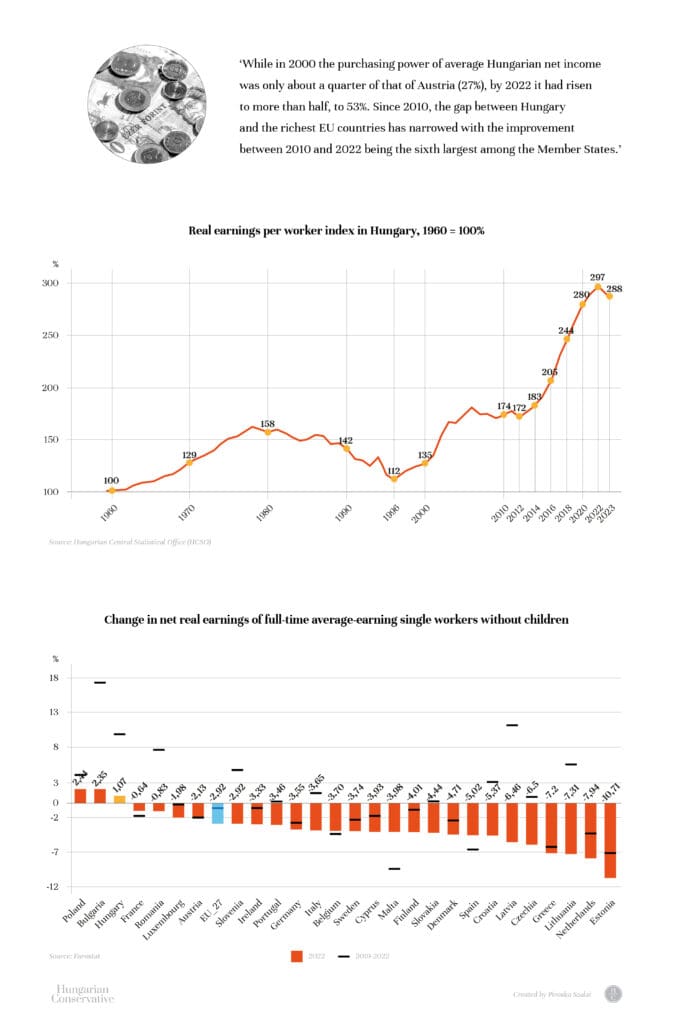

The following graph shows the development of the inflation-adjusted real value of average gross monthly earnings per full-time employee compared to 1960. It covers all economic activities, enterprises with five or more employees, all public institutions, and non-profit organizations with a significant contribution to employment.

During and after the Second World War, the whole of Hungarian society was impoverished. The country laid in ruins, with 40 per cent of its infrastructure destroyed, and there was a raging ‘world champion’ hyperinflation until the introduction of the forint on 1 August 1946 brought some stability. After the Communists came to power, everyone was obliged to work, but wages were extremely low, and when the forint was introduced, wages were on average half of what they had been in 1938, but even in 1952 the real wages of workers and employees were only two-thirds of what they had been in 1938, and there was widespread impoverishment and proletarianization. Hungary, like the countries of the Eastern Bloc, was excluded from Marshall Aid between 1948 and 1952. By 1951, the 17 Western European countries receiving aid had reached 135 per cent of their 1938 production and were well on their way to creating a welfare state. In summary, communism in Hungary entailed unnecessary economic sacrifices that diverted the development of the Hungarian economy and society from general European trends for many years.

After the 1956 revolution, apart from political retribution, there was no further reduction in real earnings. In the 18 years between 1960 and 1978, the purchasing power of average earnings rose steadily by more than one and a half times, and then fell almost continuously between 1979 and 1996 to the level of 1966.

Hungarians paid a high price during for the communist regime experiment and also during the regime change of 1990. The real value of earnings started to rise slowly only from 1997, and there was a very significant leap between 2000 and 2003.

Between 2000 and 2002, the then first Orbán government doubled the minimum wage in two years,

which then had a positive effect on wages above the minimum wage as well, and the purchasing power of earnings reached the level of 1978. The doubling of the minimum wage did not lead to an increase in unemployment, contrary to the principles written in economics textbooks.

Between 2004 and 2008, the countries that joined the EU at that time all saw significant increases in incomes and improvements in living conditions. But in Hungary, we saw a deterioration from 2006, entirely due to the mistakes of the Gyurcsány government of the time.

Turnaround after the Change of Government in 2010

The newly formed second Orbán government radically overhauled the labour tax system from 2011, abolishing the two-rate personal income tax system by eliminating the top rate,

taxing all earnings at the lower rate of 16 per cent,

and giving very significant benefits to all those with children. Previously, only those with three or more children were entitled to some small tax relief, but from 2011 even those with just one child were able to reduce their tax.

A sustained and substantial improvement in earnings started in 2013. In that year we managed to repay our previous IMF loan, giving us more freedom to reform and restructure our tax system, including reducing taxes on labour. The six-year minimum wage agreement launched in 2017 doubled the minimum wage for jobs requiring qualifications by 2022 and increased the overall minimum wage by 80 per cent. Meanwhile, the social contribution payable by employers fell from 28,5 per cent in 2016 to 13 per cent in 2022, so the total cost of labour increased at a much lower rate than the gross and net earnings of the worker.

The state is charging much less in deductions to labour, which has led to a significant reduction in black employment.

While in 2000 the purchasing power of average Hungarian net earnings per capita (excluding child benefit) was only about a quarter of that of Austria (27 per cent), by 2022 it had risen to more than half, to 53 per cent. Since 2010, the gap between Hungary and the richest EU countries has narrowed, with the improvement between 2010 and 2022 being the sixth largest among the Member States.

Even during the epidemic, real earnings in Hungary were able to grow until 2022. This is unique as in most countries in the European Union it already started to deteriorate in 2020.

In Hungary, the first year with a fall in real earnings was 2023, while in the other V4 countries there was already a significant deterioration in 2022. In Germany 2023 was the first year since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in in 2020 when real earnings improved by 0.1 per cent. Among the EU Member States, only Poland, Bulgaria and Hungary had higher real net earnings for full-time average earners without children in 2022 than in 2019, before the outbreak. This means that outside these three countries, workers across Europe were living in more difficult circumstances in 2022 than before the pandemic. Eurostat data for 2023 are not yet available, but we estimate that this trend has only worsened over the past year.

Between September 2022 and August 2023, Hungary experienced a 12-month decline in real earnings, which was shorter than in most EU countries and therefore less impoverishing.

A double-digit increase in earnings is forecast for 2024, with a high probability of a return to a real earnings growth of above 5 per cent, as was the case between 2016 and 2020. According to the forecast of the Hungarian National Bank, gross earnings are expected to grow by an average of 10–11 per cent per year, which implies real earnings growth of 5.7–6.5 pr cent, assuming inflation of 3.5–5 per cent. Of course, this can only happen if our economy is not hit by further wars or other unexpected external environmental shocks.

Piroska Szalai is a labour market expert, a researcher at Economy and Competitiveness Research Institute of the Ludovika University of Public Service.

Mátyás Zsolt Varga is a journalist at Mandiner.

Related articles: