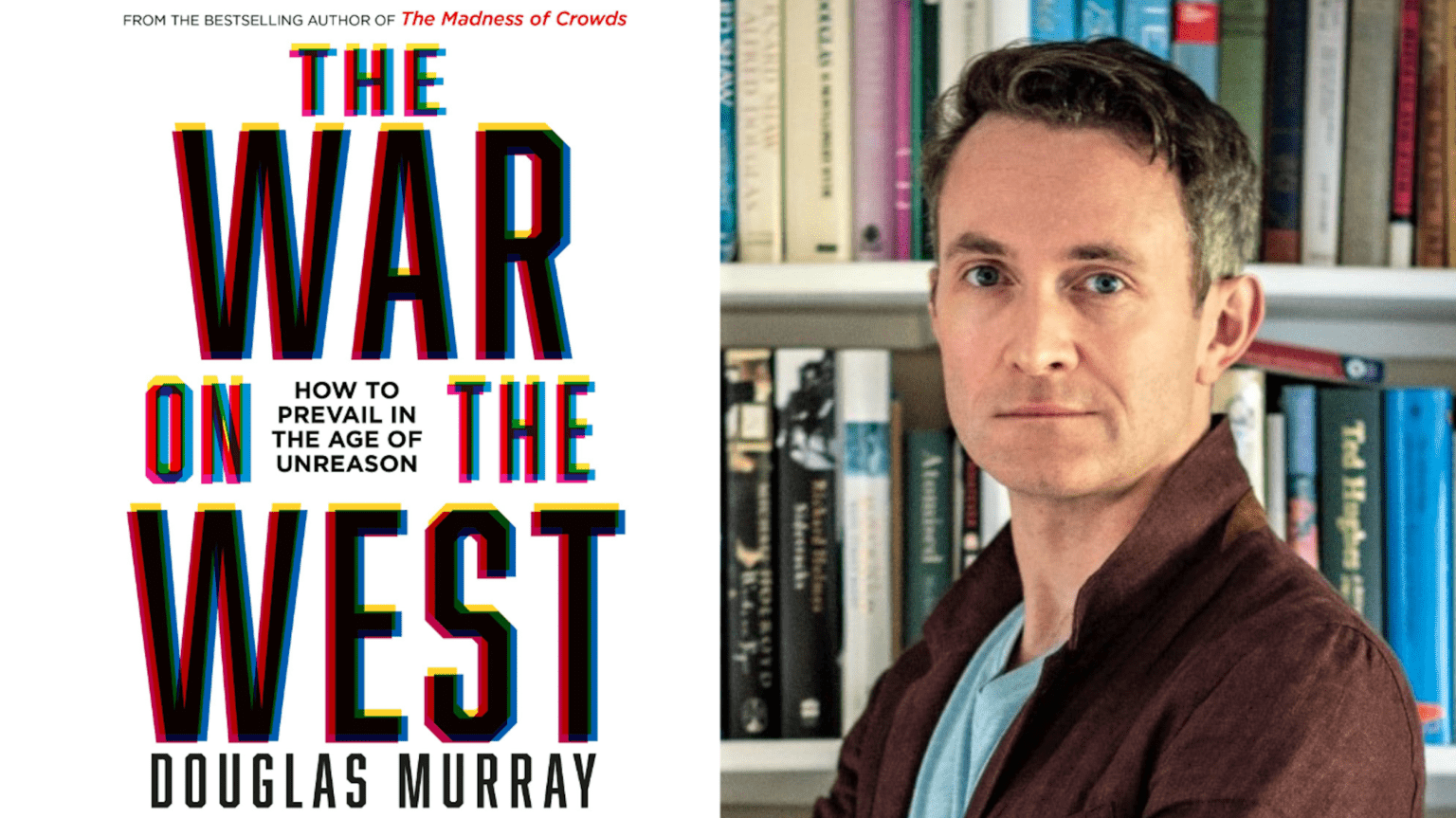

The British author and political commentator, Douglas Murray published his most recent book, The War on the West – How to Prevail in the Age of Unreason earlier this year. Murray’s previous works include The Madness of Crowds and The Strange Death of Europe. While Douglas Murray usually describes The Strange Death of Europe as a requiem for the troubled European continent, the War on the West was written in defence of the Western world and the achievements of Western civilisation against the accusations that the West thrives on oppression, white supremacy and cultural appropriation. As correctly noted by the National Review, while some examples that Murray brings up from recent years might sound familiar for a reader who eagerly follows the culture wars, the author’s ‘decision to draw them (examples from the culture war) together on a single canvas yields a picture that, like Hieronymus Bosch’s vision of hell, is more than the sum of its parts.’

The book is divided into four chapters with three interludes on ‘China’, ‘reparations’ and ‘gratitude’. The first chapter is dedicated to race. The discussion of Critical Race Theory (CRT) takes up a significant part of the chapter. CRT emphasizes structural or institutional racism and argues that as long as inequities between racial groups persist, racism is an acute problem. According to Douglas Murray, CRT has been used over the last couple of years to justify the demonisation of “whiteness” and white people. Books were written on how to raise white children in an activist, antiracist and antifascist manner, suggesting that white babies are racist from birth. The presumption of “while guilt” follows white people into their adulthood too – companies are introducing “struggle sessions” for their employees where they are compelled to disclose their white privileges and discuss how they benefit from the oppression of others. Murray draws attention to the ills of statements such as ‘a positive white identity is an impossible goal. White identity is inherently racist; white people do not exist outside they system of white supremacy’ by DiAngelo and warns of the dangers of re-racializing the Western world (p. 23). As opposed to the reimagining the West as inherently racist, Douglas Murray highlights that the West in fact is exceptionally tolerant compared to other civilizations.

CRT has been used over the last couple of years to justify the demonisation of “whiteness” and white people

The second chapter is titled ‘History’ and it discusses attempts to reimagine the foundational stories and characters of Western countries by replacing heroism with oppression as the cornerstone of our collective memory. The contemporary movements that Murray focuses on are the 1619 Project by the New York Times, and the iconoclasm of Black Lives Matter. The 1619 Project is dedicated to revising American history, and changing the US’ foundation date to 1619, when the first slave ship arrived at the North American continent, to replace 1776, when the Declaration of Independence was signed. As Douglas Murray eloquently demonstrates, the Project similarly tries to reframe Western history as a whole as a history of oppression, and Murray cites the attacks on Winston Churchill to illustrate his point. During the 2020 BLM protests, Churchill was labelled a racist many times – Douglas Murray argues in his chapter on history that if even Churchill’s achievements in the fight against Nazism can be washed away by accusations that he was a racist, the heroic narrative of the Western world falls apart and can be replaced with a narrative of oppression.

The third chapter of the book is about religion. Douglas Murray argues that with the decline of religiousness in the West, Christian faith has been substituted with ideologies, which eventually replaced God. And while the ideologues of the radical left (Marx and Foucault) are untouchable despite serious accusation of racism (Marx) and child rape (Foucault) against them, traditional churches are subjected to continual antiracist assaults. In Canada, following some unproven allegations of mass graves behind Catholic schools where abused Native American children were allegedly buried, churches were burned to the ground. To battle its alleged racism and past oppression, Murray points out, the Church of England vowed to increase black and ethnic minority service members in its churches, introduced a ‘Black Theology module’ and adopted a ‘Racial Justice Sunday’ (p. 185). These decisions and the Churches’ eagerness to accept their ‘white guilt’ prompted some to argue that Western churches now believe more in antiracism and critical race theory then in God – an opinion Douglas Murray seems to agree with in his chapter.

The fourth and final chapter is called ‘Culture’ and it aims to show that the tendency in Western culture to borrow from other peoples need not to be explained as cultural appropriation and oppression. Instead, Murray proposes an alternative explanation – curiosity, and admiration on the part of the Western world for other cultures and traditions. This chapter is convincingly underpinned by examples demonstrating Douglas Murray’s profound interest and knowledge of music, literature, art, and culture. The author started his career as an author in his late teens with a book titled Bosie: A Biography of Lord Alfred Douglas, and he has preserved his enthusiasm for literature, art, and culture ever since. In The War on the West, he guides readers through many examples from Michael Tippett to Benjamin Britten of how non-Western cultures have been used as a source of inspiration for great works of art. Theses borrowings, argues Murray, are not a form of oppression to appropriate other cultures–as usually portrayed by those waging a war on the West–but expressions of amazement, shared humanity and admiration.

The most important proposition of the book is that the attack on the West is comprehensive

Overall, the most important proposition of the book is that the attack on the West is comprehensive. Every achievement and feature of the Western world is now doubted and reframed as a form of oppression instead of as an achievement one can take pride in. From scientific methods and culture to history, freedom and individualism – everything is challenged and reduced to a form of oppression. Douglas Murray finishes his book with a warning – beware of the backlash against the demonizing of Western cultures and people living in the West, as such demonization inevitably provokes strong counter-reactions. ‘If you do not respect my past, then why should I respect yours? If you do not respect my culture, then why should I respect yours? If you do not respect my forebears, then why should I respect yours? And if you do not like what my society has produced, then why should I agree to your having a place in it? This way lies an awful amount of pain. It also concludes inevitably in conflict, solvable only by force. It is an option much to be avoided,’ Murray writes on the last pages of the book. (p. 270)

The book is now available in Hungary in various English language bookstores; Alexandra publishing house announced just four days ago that they are having the book translated to Hungarian. The translator is Miklós Stemler, who also translated Murray’s previous book, The Madness of Crowds. The Hungarian version should be available in the coming months.