In the first century AD, the border of the Roman Empire reached the Danube, and the limes followed the river from Szörényvár (today’s Drobeta-Turnu Severin, Romania) to Báziás (today’s Baziaş, Romania). Here the Danube breaks through the Carpathian–Balkan border for about 130 kilometres, and thus the river was extremely difficult to navigate, except for 70 to 80 days in drought years due to the numerous reefs and swirls. Hence the common name of this stretch: the Iron Gate.

The frontier at the Lower Danube proved to be a lasting one, inherited from the Roman Empire by the Byzantine Empire and later by the Kingdom of Hungary. In the 15th century, the Hungarian kings, especially Sigismund, tried to strengthen the Danube line against the Ottomans. King Sigismund built dozens of fortresses on the northern bank of the Danube and for a time entrusted the Teutonic Knights with its guard (1429–1432). Sigismund himself personally appeared at the Danube to capture the Ottoman castle of Golubac in 1427 and to include it in the defensive line, but he was unsuccessful. More successful was Emperor Trajan (98–117 AD), the Roman Emperor from the first province of Spain, who is not coincidentally remembered as one of the ‘good emperors’. Indeed, he was honoured by the Senate with the title optimus princeps (meaning ‘the best ruler’), which was no exaggeration, and from 103 onwards it was even printed on his coins. The Roman Empire reached its greatest territorial expansion under the rule of Trajan, as a result of his conquest in the so-called Dacian Wars (101–102 and 105–106) of the territory of the barbarian Dacian Kingdom north of the Danube, which was opposed to the Empire and which lay largely in what is now Transylvania (in today’s Romania). Trajan eventually conquered the seat of the kingdom, Sarmizegetusa (Gredistye, today’s Grădiștea de Munte, Romania), in what is now southern Transylvania, and the last Dacian king, Decebal, committed suicide in flight. His head was cut off by his pursuers and sent to Trajan, who put it on public display in Rome. At the end of the campaign, Trajan organized the defeated Dacian Kingdom into a Roman province, Dacia, which provided Rome with an abundant source of gold and silver for the next century and a half, until its emptying in 275. The emperor returned home with a huge baggage of war booty—some 250 tons of gold and 500 tons of silver. The victory was celebrated with unparalleled festivities lasting for months, with half a million people reportedly being carried off from the conquered territory.

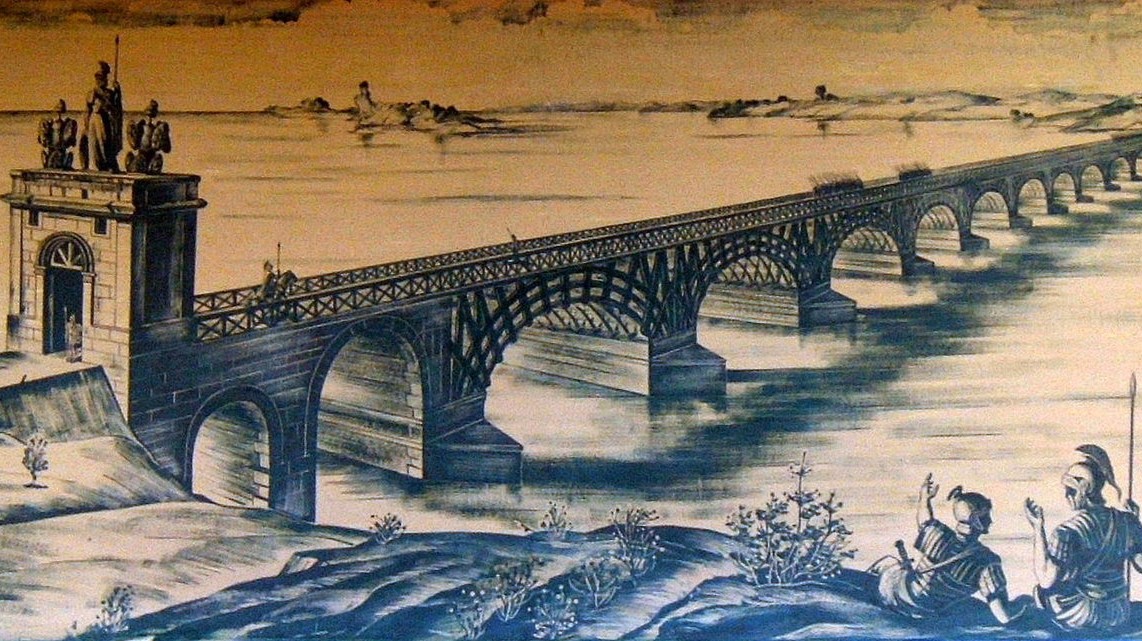

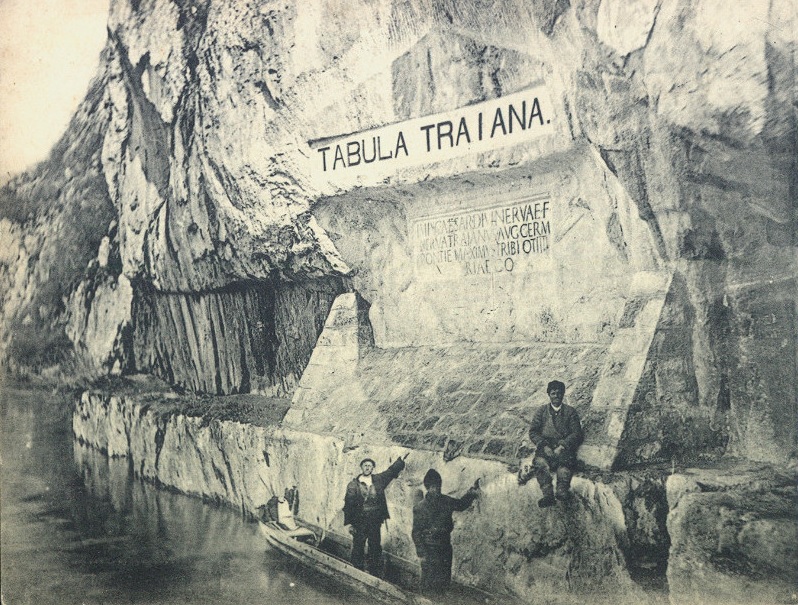

One of the lasting memories of Trajan’s campaign in Dacia is the bridge he built across the Danube to facilitate the march of his armies. The first permanent stone bridge on the Danube was built between Turnu Severin in Romania and Kladovo in Serbia, which was 1127 metres long and designed by the greatest architect of the time, Apollodorus of Damascus origin, the same master who built the Pantheon or the Alconétar bridge over the Tagus River in Spain. Built between 103 and 105, the bridge lasted only a hundred years, as Emperor Hadrian was forced to demolish it to prevent it from becoming an aid to attacks from the north. Only one of its 20 stone pillars remained near the Serbian coast, but contemporary depictions give a very accurate idea of what it looked like. Trajan placed a huge inscription on the rock wall in the Danube valley praising his work, which, although moved due to 20th-century construction, still exists today. Near the plaque is also a 40-metre portrait of King Decebal, completed a few decades ago, but illustrating the place of the Dacian King in modern 20th-century Romanian historical memory.

‘One of the lasting memories of Trajan’s campaign in Dacia is the bridge he built across the Danube’

This is no coincidence since the evidence for the Dacian–Roman theory of the ancient origins of present-day Romania is precisely the period of the Roman occupation of Dacia. According to this theory, based on the affinity between Romance and Latin, Romanians in Transylvania appear in sources from the Middle Ages onwards as descendants of the former Roman inhabitants of Dacia, the Romanized Dacians, and Roman settlers. According to the theory, when the Romans emptied the province, the Dacians stayed behind in masses and lived there during the Middle Ages. The so-called Daco–Romanian theory was first formulated by Italian and Transylvanian Saxon humanists in the 15th and 16th centuries, and its validity remained a subject of debate for centuries, not only among Hungarian and Romanian historians but also among the Hungarian and Romanian public, overwhelmed by nationalist sentiment.[1]

Trajan erected the so-called Trajan’s Column in Rome to commemorate the Dacian campaigns. Rising 38 metres above the forum, the column was topped with a bronze statue of the Emperor (now it is St Peter’s) and decorated with scenes from the campaign against the Dacians. The spiralling series of reliefs, with more than 2,600 figures in 155 scenes, was in fact an ancient comic strip. The column is a very valuable resource for researchers, as it gives an almost complete picture of the costume, weaponry, and warfare of the period. The column also serves as a tomb, as the Emperor’s ashes are buried in its foundation.

The question is, why did Christian posterity preserve the memory of a pagan emperor who was hostile to Christians? Part of the explanation is that the pagan Romans themselves held him in high esteem. The emperors of the 3rd and 4th centuries were usually greeted with the following exclamation: ‘Be more fortunate than Augustus and better than Trajan.’ A late antique predecessor of the medieval king mirror genre is the so-called Institutio Traiani (Institution of Trajan), written in the 4th and 5th centuries, in which his fictional tutor Plutarch addresses him with instructions. The work was well known in the Middle Ages from the 12th-century Bishop of Chartres John of Salisbury’s work Policraticus.

On the other hand, the Emperor’s correspondence in 113 with Pliny, governor of the Asia Minor province of Bithynia, was also read already back in the Middle Ages, recording the first authentic description of Christians by a non-Christian author. In it, Pliny asks the Emperor for advice on how to deal with the accused Christians on trial for Christianity. Linked to this was the question of whether giving Christian ‘names’ itself was a crime, or only the ‘crimes’ associated with it, and whether Christians should be investigated. The Emperor replied very cautiously: ‘They are not to be sought out; if they are denounced and proved guilty, they are to be punished, with this reservation, that whoever denies that he is a Christian and really proves it—that is, by worshiping our gods—even though he was under suspicion in the past, shall obtain pardon through repentance. But anonymously posted accusations ought to have no place in any prosecution. For this is both a dangerous kind of precedent and out of keeping with the spirit of our age.’[2]

It is not surprising that in the most popular 13th-century hagiographical manual of the Middle Ages, Jacobus de Voragine argued that the Emperor was a pagan and thus doomed to damnation, but that he was taken to Paradise through the prayers of Saint Gregory the Great (r. 590–604): ‘One day many years after that emperor’s death, as Gregory was crossing through Trajan’s forum, the emperor’s kindness came to his mind, and he went to Saint Peter’s basilica and lamented the ruler’s errors with bitter tears. The voice of God responded from above: ‘I have granted your petition and spared Trajan eternal punishment.’[3]

The protection of the Lower Danube line was primarily a strategic issue in ancient times and the Middle Ages, but it became a commercial problem in the modern era: it obstructed shipping, preventing direct communication between Hungary and the Black Sea ports. István Széchenyi (1791–1860), a prominent politician of the 19th-century Hungarian reform era, known as ‘the Greatest Hungarian’, recognized the importance of river regulation and enlisted the help of Pál Vásárhelyi, an eminent engineer of the time, to design a scheme. Their main aim was to make the Lower Danube navigable so that steamships could transport Hungarian goods to the eastern markets unhindered. In 1830 Széchenyi set sail in his galley Desdemona and surveyed the area, sailing along the Danube from Pest to the estuary. In 1833 Széchenyi was already in charge of the works as royal commissioner, but the project was beyond his means, and thus he was unable to clear the waterway of obstacles completely. Therefore, as a supplementary plan, the construction of a road, later known as the Széchenyi Road, was started. Over the next few years, 122 kilometres of road were built along the coast, carved into the cliff, to allow ships to be towed.

‘The protection of the Lower Danube line was primarily a strategic issue in ancient times and the Middle Ages’

At low water levels, the ships’ cargo could be loaded onto wagons to ensure continuous transport. The road between Báziás and Orsova (Orșova, today’s Romania), which was carved in rock in places, was completed by 1837. A barrage built between 1964 and 1972 raised the water level by 15 to 30 metres, which covered long stretches of the road. Today, only a short stretch remains, where fortunately a plaque commemorating Hungarian Minister of Trade Gábor Baross from 1890 can still be seen. In the last years of the 19th century (1890–1899), the Lower Danube was further regulated by the construction of a ‘canal’ in the rocky wall of the riverbed, several kilometres long, 80 metres wide, and 3 metres deep. However, Széchenyi was not forgotten either: in 1885, the Association of Hungarian Architects carved his name into the rock above Széchenyi Road, which has now been covered by water. To replace it, a new plaque was erected in 2018, with the support of the Hungarian Government, to mark the European significance of the investment made by Hungarian engineers and politicians during the 19th century.

[1] Gh. A. Niculescu, ‘Archaeology, Nationalism and “The History of the Romanians”’, Dacia N.S. 48–49, 2004–2005, pp. 99–124.; Béla Köpeczi, Gábor Barta, István Bóna, László Makkai, and Zoltán Szász (eds.), History of Transylvania, Budapest, 1994, pp. 183–188, 426–428.

[2] Pliny, Letters 10.96-97, transl. A. N. Sherwyn-White (https://faculty.georgetown.edu/jod/texts/pliny.html).

[3] Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints, trans. William Granger Ryan, with an introduction by Eamon Duffy, Princeton and Oxford, 2012, p. 178.

Read more: