On Wednesday, 22 February, the Danube Institute hosted a lecture by Dr Brittany Pheiffer Noble, an expert on 20th-century Russian intellectual history and religion. The expert offered some insights into how the Russian Orthodox Church went from counterculture during Soviet times to an establishment subculture in as little as thirty years.

During the time of Tsarist Russia, the Orthodox Church was arguably the largest religion in the Empire. However, soon, after the Bolshevik Revolution, religion and religiosity were vilified and prosecuted.

Over the course of the Russian Civil War and the Stalinist terror, 100,000 priests and monks were killed, church property was seized, and churches were closed down.

The oppressive and violent attack on the church brought Russian orthodoxy to the precipice by the time World War II started. In an attempt to boost morale in the war-torn and starving country, churches were allowed to reopen—the Church was far from being freed from oppression, however. After decades of banishment, the priests who were allowed to preach could study only in a heavily state-supervised setting, sometimes having access only to limited theology education before starting their services.

In the years following Stalin’s death, the serious restrictions on the church were not eased. For instance, as Dr Brittany Pheiffer Noble said, rituals that are fundamental elements of Orthodox religious practices, such as pilgrimages and baptism, were banned even under Khrushchev.

In the late socialist period, with the growing popularity of samizdat, religious writings became available again to the Soviet dissident public. Apart from the famous works of dissidents such as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, many old Pravoslav texts were also published and disseminated. In Russian intellectual circles, Orthodoxy was increasingly seen as a force that can recover a lost Russian identity that was suppressed by the Soviet Union’s ideal of a ´new Soviet man´. With glasnost and perestroika in the 1980s, churches gradually received more freedom to preach and organise religious events.

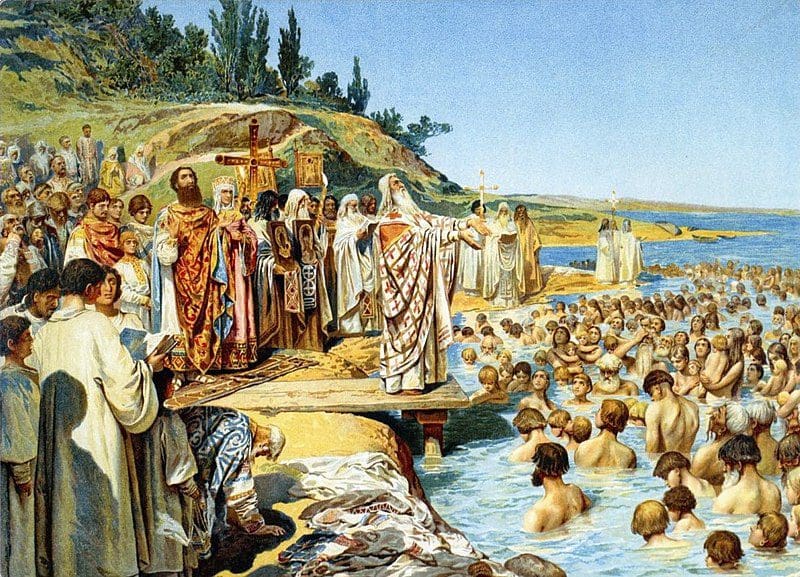

In a historic turn, explained Dr Brittany Pheiffer Noble, the Soviet state that prosecuted Christianity just a couple of decades ago co-hosted a series of memorial events marking the 1,000th Anniversary of the ‘Christianization of Rus’ in 1988.

The series of events, taking place May–June 1988, was meant to celebrate the introduction of Christianity under Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavich’s rule in 988. It was originally planned to be hosted by the Russian Orthodox Church only, but the state decided to step in too, marking a shift in Soviet policy regarding religion. As a show of goodwill, the Danilov Monastery was given back from state to church control. The monastery is the centre of the Moscow Patriarchate even today.

Soon after the celebrations, however, the Soviet Union collapsed, and the Church found itself in a new world. The dissolution of the Soviet Union brought about a remarkable window of opportunity for new faiths to spread in the Russian Federation. It was not until 1997 that the Russian Orthodox Church and other established religions received protected status from Moscow. The protected status that was granted to religions such as Orthodoxy, Judaism, Buddhism, and Islam gave extra benefits and preferential treatment to these churches. Over the years, and increasingly under Putin’s presidency, the Orthodox Church became recognised as an intrinsic, historical part of the Russian Federation. The 2020 constitutional changes, for instance, acknowledged the Church as being one of Russia’s historical state-forming entities, giving further privileges to the Church.