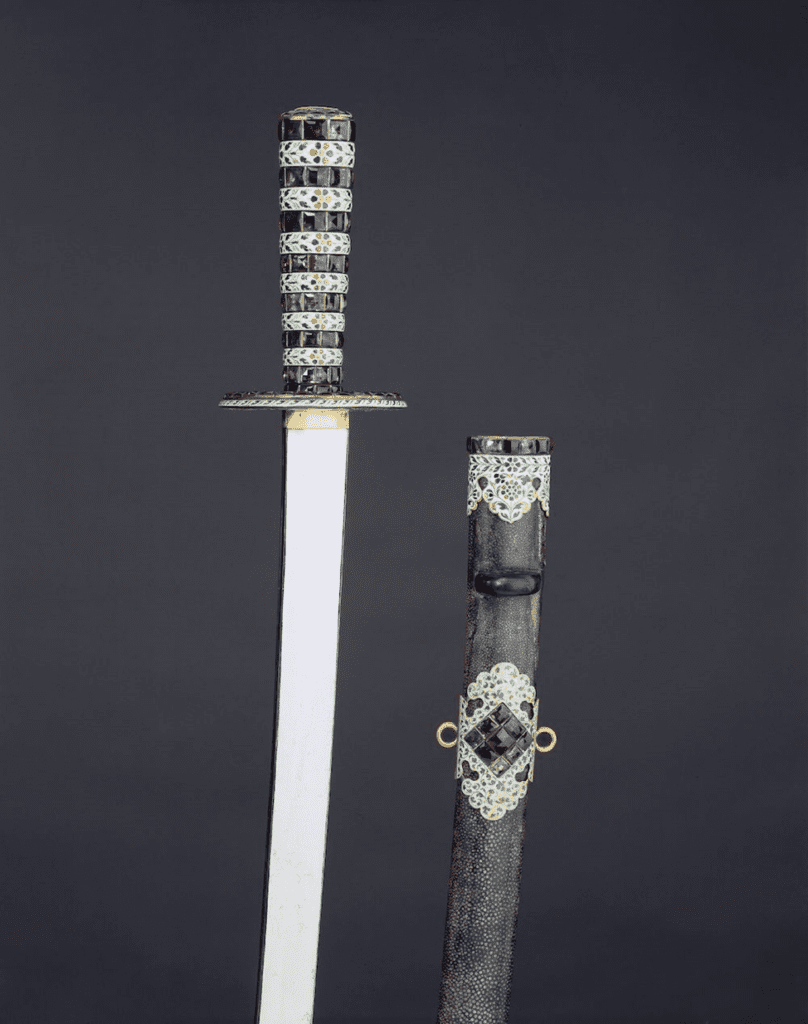

An extraordinary cultural cross-pollination event took place in the principality of Transylvania in the 1670s. A Hungarian weaponsmith called Thomas Kapustran, active in the city of Kolozsvár (today Cluj-Napoca, Romania) around 1670s, ostensibly decorated a weapon of apparent East Asian blade and scabbard design that seemingly looked like the type of weapon that the Japanese warrior caste, the Samurai, historically used in warfare. How and why did Thomas Kapustran make this ornate masterpiece of weapon craftsmanship, and what historical circumstances enabled him to do so?

It is hard to imagine something more geographically and culturally more separated than late 17th century Transylvania and Japan of the same period. Isolated from each other by thousands of miles, dozens of cultures, and the immense expanses of Eurasia, hardly any cultural connections between Hungary—or then independent Turkish vassal Transylvania—and Japan can be attested to have existed back then. At the time, Hungarian lands were split between the Ottoman and the Habsburg empires. Since 1630s, on the other hand, Japan had been pursuing the isolationist sakoku (‘closed country’) policy, making it insurmountably hard for any outsider to enter the country.

However, at the times of the forging of this mysterious sword Transylvania was an independent principality, ruled by Mihály Apafi, who got the seat from the Ottomans as their vassal. Albeit overall Hungary suffered tremendously from the period of the Ottoman wars and was not politically united, Transylvania, if taken alone, was enjoying relative prosperity, and a unique version of Hungarian culture of its own developed and thrived there.

Given that the Principality wisely decided to pursue a policy of religious tolerance considering its policultural society, it is no surprise it attracted talented craftsmen,

such as armorers, smiths, jewellers and other artisans from all across Europe, who migrated there from less tolerant and more populated regions of the continent like Bohemia, Bavaria or Saxony.

Also, the region was geographically located between different civilizations and continents-spanning empires, which naturally made it a focal point of long-distance trade. Moreover, Transylvania also had the abundant gold and silver deposits of the Carpathian Mountains at its disposal, while also maintaining commercial connections with European centres of precious metals trade such as Nuremberg or Augsburg. Such was the atmosphere the talented Hungarian (and possibly partially German) smith Thomas Kapustran operated in, gaining prominence for his impeccable skills in Kolozsvár which he was a resident of, and the entire Transylvania as a whole. Among a multitude of beautiful blades he decorated and manufactured, the Katana-resembling sword he encrusted with amethysts and whose handguard he opulently painted stands out for a number of reasons.

First and foremost, even though Transylvania indeed stood at the crossroads of cultures and civilizations and had amazing trade connections, there is still no definitive explanation as to how and via what route the original blade that was subsequently refurbished and ornated by Kapustran arrived in Transylvania. To be precise, it is not that there are no explanations, the problem is that there are simply too many of them. As it has been mentioned above, Transylvania used to be an Ottoman vassal, which in turn had strong links with the East; however, at no point in its history had the Ottoman Empire direct contact with Japan (geographically speaking), although it is totally plausible the blade first resided somewhere in East Asia and was brought to Turkey later by merchants. Russia in turn stretched roughly as far as the Pacific and the Sea of Okhotsk at that time, but no meaningful interaction had occurred with the Japanese until the first years of the 18th century. It is also true that Transylvania frequently changed allegiances and allied itself more with the Habsburgs at times, which opened up possibilities for more contact with the Western seafaring empires which had been trading with Japan by that time. In any case, the fact it was brought to Europe for decorative purposes is hardly debatable, as even without the easily destructible ornate decoration made by Kapustran, which rendered the weapon practically useless on the battlefield, the original blade was hardly useful in other warfare contexts outside East Asia and Japan. Arms and armour outside these countries were simply too different to accommodate for this blade. Thus, given its décor and shape, there is no reason to assume it was actually wielded by soldiers of either side during the Turkish wars.

But after the sword had made its way to Transylvania into Kapustran’s hands and acquired the beautiful stone decorations of the handle and the floral painting on its handguard of Middle Eastern design, the bizarre journey of the blade didn’t end. Just like no one knows who its previous owners were before Thomas Kapustran got his hands on it, similarly no one knows whom Kapustran so lavishly embellished it for. Some have speculated that since it lacked any real battle use and was literally delivered from the other end of the world, it could have been made only for someone incredibly rich, such as, for example, for someone from the court of Mihály Apafi, possible even Prince Apafi himself. If true, that would render this piece of weapon craftsmanship

a truly unique object with no analogues, a combination of East Asian weapon design, Middle Eastern art influences and Transylvanian–Hungarian court culture.

These are interesting theories about it, but the actual subsequent (as well as the previous) story of the sword is not known. No documents, no acts of purchase, no witnesses reporting on seeing this special sword have been uncovered. But ten years after being refitted by Kapustran, in 1684, it appeared in the inventory of Dresden’s ‘Türckische Cammer’ (Turkish Chamber), where it has been displayed up to this day.

While except for these few known pieces of the puzzle its story and origins remain obscure, the Transylvanian Samurai sword of Thomas Kapustran is certainly a manifestation of the complexity and richness of Hungarian history. Despite being torn apart by two empires and enduring a century of wars, Transylvania still held a remarkable position in the world. So significant was its influence, grandeur, and civilizational level that it could procure luxury goods from distant and isolated lands like Japan.

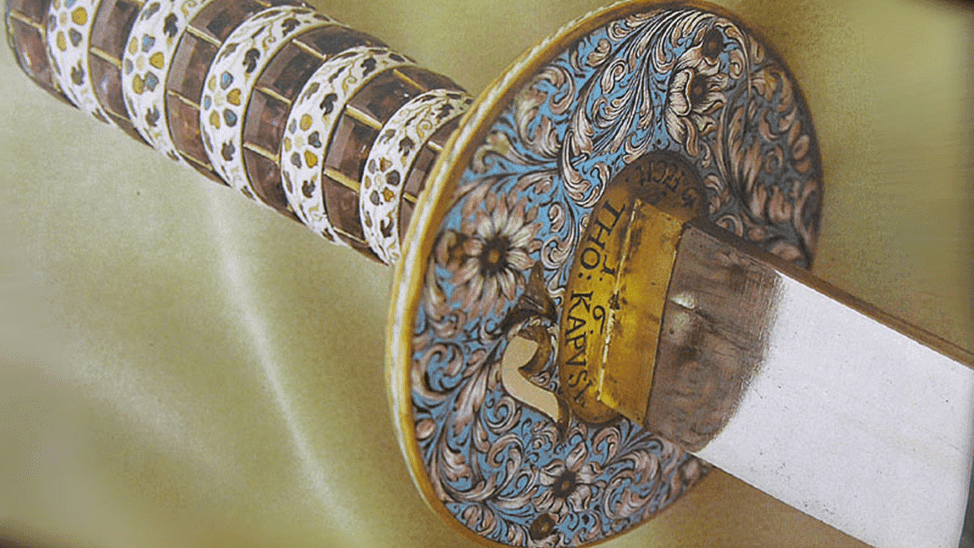

The sword’s handguard (this part of the sword is known as tsuba in Japanese) with elegant oriental Persian-Turkish floral patterns and engraving added by Kapustran. A small gold plate can be seen with the engraving ‘Tho: Kapusi.No: Transilvan FeCit. 1674’, indicating the smith, the place of manufacturing and the year. Source: https://mhistories.hypotheses.org/files/2021/04/Koelmel_Bild_2-scaled.jpg

After the sword had made its way to Transylvania into Kapustran’s hands and acquired the beautiful stone decorations of the handle and the floral painting on its handguard of Middle Eastern design, the bizarre journey of the blade didn’t end there. Just like no one knows who its previous owners were before Thomas Kapustran got his hands on it, similarly no one knows whom Kapustran so lavishly embellished it for. Some have speculated that since it lacked any real battle use and was literally delivered from the other end of the world, it could have been made only for someone incredibly rich, such as, for example, for someone from the court of Mihály Apafi, possible even Prince Apafi himself. If true, that would render this piece of weapon craftsmanship a truly unique object with no analogues, a combination of East Asian weapon design, Middle Eastern art influences and Transylvanian–Hungarian court culture.

These are interesting theories about it, but the actual subsequent (as well as the previous) story of the sword is not known. No documents, no acts of purchase, no witnesses reporting on seeing this special sword have been uncovered. But ten years after being refitted by Kapustran, in 1684, it appeared in the inventory of Dresden’s ‘Türckische Cammer’ (Turkish Chamber), where it has been displayed up to this day.

While except for these few known pieces of the puzzle its story and origins remains obscure, the Transylvanian Samurai sword of Thomas Kapustran is certainly a manifestation of the complexity and richness of Hungarian history. Despite being torn apart by two empires and enduring a century of wars, Transylvania, just one of its regions, still held a remarkable position in the world. So significant was its influence, grandeur, and civilizational level that it could procure luxury goods from distant and isolated lands like Japan.

Related articles: