László Salgó was born on 23 April 1910 in Budapest. His father, Miksa Salgó (Schwarz) (1880–1958), worked at the Rákoskeresztúr Jewish cemetery and had roots in Nógrád, while his mother was Kornélia Hecht. László Salgó earned his doctorate in 1933 and was ordained as a rabbi in 1935. He began his career as an assistant rabbi at the Józsefváros synagogue. In 1944 the Arrow Cross forces deported him to forced labour service, an experience he documented in his memoir written in 1984.[1] During the Holocaust, he lost two of his siblings. From 1945 he served as Chief Rabbi, and from 1959 he was the director of the Budapest Rabbinate and a lecturer at the National Rabbinical Seminary. From 1971 until his death, he was Deputy Chief Rabbi of Hungary while also serving as the Rabbi of the Dohány Street Synagogue in Budapest. In 1980 he became a member of the Communist parliament. Following the death of Sándor Scheiber in March 1985, he became the director of the Rabbinical Seminary, a position he held only for a short time until his own passing on 24 July 1985.[2]

As documented in multiple historical works, Salgó was identical to the state security agent codenamed ‘György Sárvári’, who, over nearly two decades of activity, reported on his students, friends, colleagues, and, most notably, Sándor Scheiber.[3] Four ‘M’ (munka—work) files documenting his activities have survived, spanning several hundred pages and detailing his work as an agent. Historians largely assess his role based on these records. While we do not intend to absolve him of his actions, we believe certain documents may help readers gain a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of the story.

Salgó’s so-called ‘6-os karton’ (personal record card) and ‘B’ (beszervezési—recruitment) dossier have not survived, so the exact timing and circumstances of his recruitment remain unknown, though the broad outlines of the story can be reconstructed. Even before the 1960s, ÁVH (State Security Bureau) reports mentioned Salgó as a rabbi with Zionist sympathies.

‘Salgó likely became a target precisely because of his Zionist stance’

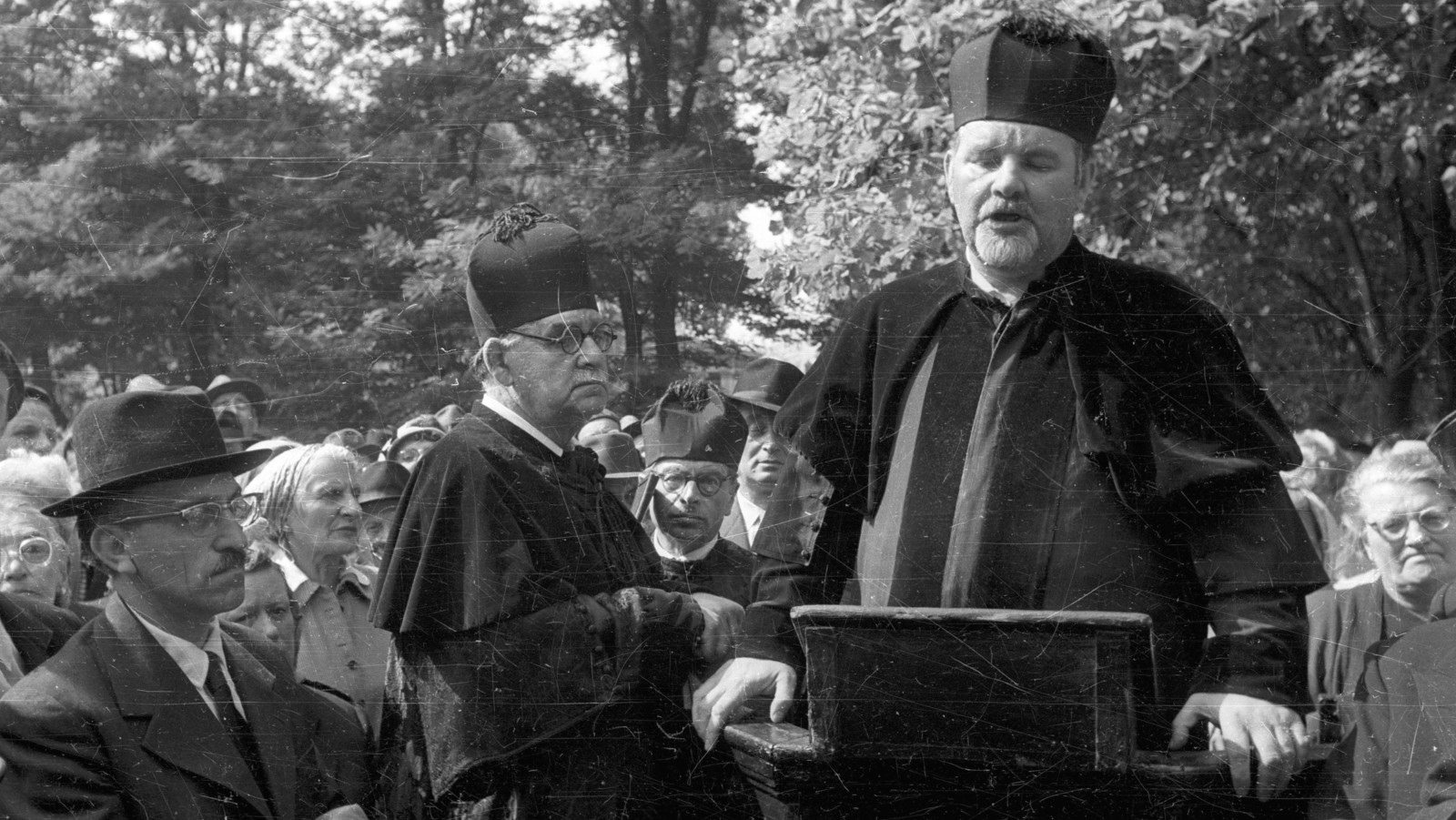

This may seem surprising in light of his later, well-known and vocal anti-Zionist, anti-Israel statements. However, there is a clear connection between the two: Salgó likely became a target precisely because of his Zionist stance, and after getting into trouble, he was offered a way out through recruitment. Following this, state security used him for its own anti-Israel agenda. His early Zionist sympathies are well-documented. After the proclamation of the State of Israel on 14 May 1948, Jewish communities in Hungary organized a series of lectures and celebratory services, during which Salgó himself delivered an enthusiastic speech.[4]

On 2 February 1951 an agent with the cover name ‘Kékes’—who reported from the highest echelons of the Budapest Jewish Community—submitted a report to László Tölgyesi, an ÁVH lieutenant (who later transitioned to the Ministry of Interior’s III/III division before retiring in 1963). The report stated that ‘among the currently active rabbis, the following individuals were involved in leading and organizing the Zionist movement…and still maintain Zionist connections today: Dr László Salgó, district rabbi of Nagyfuvaros Street, was also an active participant in the Zionist Federation.’[5] In the fall of 1959 ‘Xavér’, an agent of the Ministry of Interior’s II/3-a sub-department, who we have already introduced, reported: ‘there are no political factions among the rabbis; the only thing they agree on is their hatred for Henrik Fisch and István Végházi…They are highly unstable but still listen to each other and stick together: (Sándor) Scheiber, (Imre) Benoschofsky, (József) Schindler, (József) Schweitzer, (László) Salgó, and as quasi-members, (Miklós) Bernáth, (László) Hochberger, (Artúr) Geyer.’ These sources still categorized Salgó as a Jewish leader critical of the regime, even placing him among those with Zionist affiliations.[6]

Subsequently, the Ministry of Interior’s II/5-c sub-department included Salgó in its work plan dated 14 March 1962, which focused on ‘processing Zionist illegal activity’. While the text primarily concentrated on Rabbi Sándor Scheiber, it contained a passing remark about Salgó: ‘We have begun studying Chief Rabbi Dr László Salgó among Scheiber’s contacts for the purpose of agent recruitment. To concretize morally compromising materials, we will organize surveillance and photography. Deadline: 15 April 1962.’[7] The text does not specify what ‘moral compromising’ was involved, but a fellow rabbi recalled Salgó as follows: ‘When I was drinking black coffee with others in the Eastern Railway Station restaurant one time, I heard his distinctive, unmistakable cough, clearly caused by some illness. He was sitting there with an unknown woman. There was an unspoken understanding between us: he would not criticize my appearance, and I would pretend I hadn’t witnessed the date unfolding in the Eastern Railway Station restaurant.’[8]

Leading such a private life was dangerous for religious figures, as they later provided excellent opportunities for state security to approach them. The following report from the Ministry of Interior’s II/5 department, dated 12 April, once again identified Salgó as a Zionist opponent: ‘Within the denomination, there is currently active Zionist, pro-Israel propaganda being conducted through the use of religious institutions and religious education. Active religious education outside of school is ongoing. According to our information, 824 schoolchildren in Budapest have been involved in out-of-school religious education. It is noteworthy that the reactionary Zionist rabbis lead the largest groups. Dr László Salgó’s group, for example, exceeds 150 members.’[9]

This did not rule out the possibility of targeting him for recruitment, and in fact, as a Zionist, his intelligence opportunities were ideal since a target would have been less likely to open up to a person with a known affiliation to the Communist system. A week later, the same department briefly recorded: ‘Regarding the case of Dr Sándor S(cheiber)…we will continue studying Dr László S(algó). Through a combination of methods, we will compromise him on moral grounds to carry out his recruitment.’[10] The term ‘combination’ unfortunately does not reveal much, but in professional jargon, it refers to ‘the simultaneous or consecutive application of operational measures, which involved the use of one or more secret investigative (operational) tools to increase the effectiveness of the action.’[11] Here, the term likely referred to personal (agent-based) action and the making of covert recordings.

As we noted, his personal record card has not survived, but the first report in ‘Sárvári’s’ initial working dossier, dated 16 June 1963, about rabbi László Hochberger showing him Israeli newspapers, was followed by a comment from his handler, Ferenc Mélykuti, a second lieutenant from the Ministry of Interior’s III/III-2-a sub-department. The note read: ‘This is the first report since the agent’s recruitment. The agent has, by now, completely calmed down, responds well to the questions, and appears to be sincere. He emphasized again that he wanted to prove his loyalty to his country through his work. This is supported by the report he submitted.’[12] The term ‘calming down’ was a phrase used by handlers in cases of ‘recruitment based on pressure’—ie blackmail. This fits with the above work plan, which indicated that they intended to recruit Salgó in such a way.

Subsequently, Salgó began a lengthy, fruitful collaboration with state security, which brought him numerous opportunities for career advancement, Western trips, and other advantages. One of the low points of his activities occurred in May 1973, when he had to steal typed letters from Sándor Scheiber’s office to have them subjected to handwriting analysis. According to the relevant report: ‘The attached typed letter beginning with “Dear Friend!” was written on an Olympia typewriter in the Rabbinical Seminary’s office on 23 May 1973. This typewriter is regularly used by Lászlóné Kátai (Scheiber’s secretary). However, it is freely accessible on the desk, and anyone can use it.’ The evaluation of the report: ‘The agent carried out the task of obtaining the necessary sample from the typewriter in the Rabbinical Seminary’s office. The only shortcoming is that the text is quite brief…His task was well executed.’[13]

‘Public opinion considers him to be a pretentious, malicious person’

However, this does not mean that his handlers were always satisfied with him. A fundamental procedure was that agents were also monitored to weed out double-dealing, treacherous agents. In October 1976 an unknown agent reported about Salgó: ‘László Salgó has returned from his trip to England and did not comment on his experiences in front of the students and teachers. Salgó László has very poor relations with the students and teachers, and public opinion considers him to be a pretentious, malicious person.’[14] It should be added that the poor relationship was obviously partly due to his forced loyalty to the regime, which later severely limited his intelligence-gathering opportunities.

A year later, he appeared directly as a target person. The document titled ‘The 1977 Work Plan for the Elimination of Zionist Religious Reaction’ from the Ministry of Interior’s III/III-1 division, dated 7 December 1976, listed the main individuals under surveillance. The first two names—Sándor Scheiber and Tamás Raj—were not surprising, as they had been harassed by the state security for decades. The third case, however, is much more surprising and worth quoting in detail:

‘Name: Sándor Zoldán. The target person is 65 years old and is the custodian of the Dohány Street Synagogue. His son is a lieutenant colonel in the Israeli army and regularly visits him. According to network reports, Zoldán, under the protection of Chief Rabbi Salgó, organized a group of young people at the Dohány Street Synagogue, holding regular meetings where they engage in extreme Jewish nationalist discussions. The group—based on primary data—consists of 50–60 people. Recently, left-wing and right-wing extremists have also appeared. Zoldán regularly brings in records and propaganda materials from Israel, using and distributing them within the group.

- We propose to open a preliminary investigation and develop an action plan. Deadline: 28 February 1977.

- We will determine the participants in the group and investigate their social background through network and operational technical means. Deadline: 20 June 1977.

- We will investigate the location, system, and content of the meetings. Deadline: 20 June 1977.

- Depending on the results, we will propose initiating a confidential investigation or discontinuing the activity. Deadline: 30 June 1977.’[15]

A few remarks are worth noting regarding the above. The term ‘left-wing and right-wing extremists’ should obviously be placed within the political spectrum of the Kádár regime, where even a stray social democrat or a left-wing Zionist could be considered ‘right-wing’. While one might speculate that Salgó may have merely allowed Zoldán’s group to function on the orders of his handlers, the same document, a few pages later, shared the following regarding ‘unreliable agents’:

‘Our networks often provide parallel reports about individual events, allowing us to continuously verify them by comparing the content of the reports. During this process, it was found regarding agent “Sárvári”…that due to various subjective circumstances, he has altered or concealed from us certain matters that are important from an operational point of view. Therefore, it became necessary to use operational technical tools to obtain data about him, which we could use to align him with our objectives. As a result, we are implementing 3/e tools (wiretapping of a room) at “Sárvári’s” workplace and placing him under 3/a supervision (wiretapping of a phone). Deadline: 31 August 1977.’[16]

Unfortunately, it is not known how the aforementioned preliminary check or investigation ended. However, it is worth noting that even then, a person could have been the target of an undercover investigation, even if their cooperation with the Kádár regime seemed seamless at first glance. In Salgó’s case, trust may not have fully faltered, as he later received significant positions. It seems likely that in 1980, when he became a member of parliament, he was excluded from the network—not because he had become unreliable, but because, at such times, the authorities generally felt that there was no need for the person to continue their involvement in the network. However, without the personal data card, this remains a mere assumption.

Starting from the mid-1970s, the sources became significantly scarcer, but Salgó’s name appeared several times in the so-called Daily Operational Intelligence Reports (NOIJ). These reports were compiled between 1979 and 1990 by the state security agencies and were used to brief the internal ministry leadership. Salgó was included in the NOIJ even two years before his death, as in 1983, Nicholas M Salgo, the rabbi’s cousin, became the new US ambassador to Hungary. The counterintelligence officers were waiting for him to establish contact with Salgó.[17]

The above does not drastically alter the image of Salgó that has been established in the scholarly literature, but it helps to understand the background of the agent, some of his motivations, and illustrates how complex the relationship between the agent and state security might have been in the Kádár regime. A complete, primary-source-based investigation into Salgó’s activities is yet to be written. In any case, we can agree with the rabbi in the sense that, as he stated at the beginning of his Holocaust remembrance: ‘Nothing can be properly examined without understanding the chain of causes.’[18]

[1] Salgó László, ‘Emlékeimből’, Évkönyv — Magyar Izraeliták Országos Képviselete, 1983–1984, Ed. Scheiber Sándor, 301–309.

[2] For his biography, see: György G Landeszman, ‘Ordained Rabbis’, In: The Rabbinical Seminary of Budapest, 1877–1977, A Centennial Volume, Ed. Moshe Carmilly-Weinberger, New York, Sepher-Hermon Press, 1986. pp. 303–320, here 315., and also Új Élet, 1 Dec 1958.

[3] Kovács András, A Kádár-rendszer és a zsidók, Bp, Corvina, 2019, p. 316, footnote no 29, and Novák Attila, ‘Párbeszéd? Zsidó-keresztény (katolikus) közeledési kísérletek az 1960-as évek Magyarországán—az állambiztonsági dokumentumok tükrében’, Regio, 2022/4, 68–91, here 85.

[4] Új Élet, 11 Dec 1947.

[5] Állambiztonsági Szolgálatok Történeti Levéltára (from here on: ÁBSZTL), 3.1.5. O-17169, 147.

[6] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.5. O-17169, 219.

[7] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.5. O-17169, 274.

[8] ‘A Síp utcai szocializmus: a Népköztársaság megszűnt, fel vagyok mentve’, Milev.hu, 20 Dec 2022. https://www.milev.hu/interviews/category/kardos-peter-forabbi?lang=en

[9] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.5. O-17169, 237–238.

[10] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.5. O-17169/1, 155.

[11] https://ugynoksorsok.hu/segedletek/a-fontosabb-allambiztonsegi-szakkifejezesek-jegyzeke

[12] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.2. M-37809, 10.

[13] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.2. M-37809/3, 67–68.

[14] ÁBSZTL, 3.1.5. O-17169/4, 287.

[15] 3.1.5. O-17169/5, 326.

[16] 3.1.5. O-17169/5, 334–335.

[17] ÁBSZTL, 2.7.1. III/II-210-212/7./1983.10.26.

[18] Salgó, ‘Emlékeimből’, Op. cit. 301.

Related articles: