The following is a translation of an article written by Emese Hulej, originally published in Hungarian in Magyar Krónika.

In its series about Hungarikums, Magyar Krónika presents the trade secrets of the treasures of the Collection of Hungarian Values—this time, the overwhelming success of the famous Hungarian Zsolnay Porcelain and Ceramics and the factory’s history.

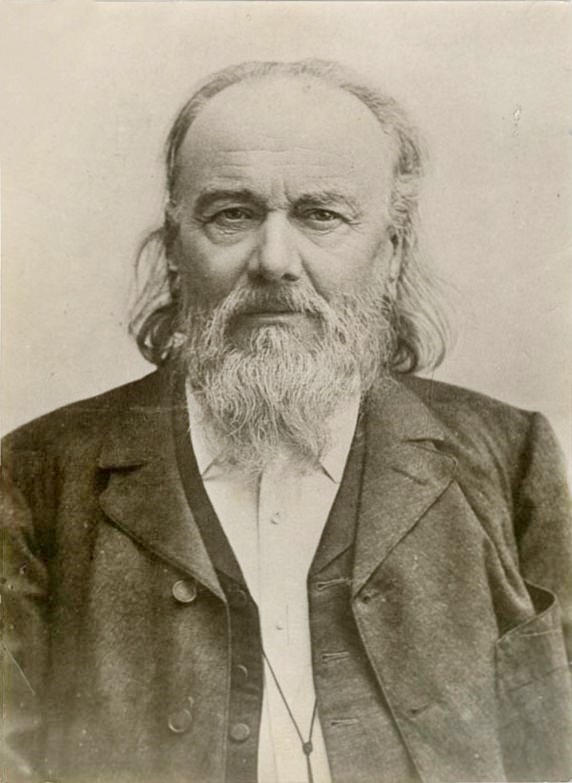

An old alchemist farmer. This is how painter József Rippl-Rónai described the bearded Vilmos Zsolnay, always wearing a long woollen coat, who by the end of the 19th century had made his factory the largest world-famous ceramics factory in the monarchy.

Like Coca-Cola or Unicum, Zsolnay also has a closely guarded secret: the composition of a certain eosin glaze that Vilmos Zsolnay developed with Vince Wartha and Lajos Petrik. The bowls, vases, and sculptures, coated with this distinctive bluish glaze, look as if they have been mysteriously painted with light itself. That is why this material is named after Eos, the Goddess of Dawn.

If not a secret, the brand is just as much about its unique painting technique as the glaze. In other domestic porcelain factories, the firing temperature at which the glaze melts onto the surface of the ceramics is eight hundred and twenty degrees, but in the Zsolnay Factory, it is much higher. They use a practically coloured glaze, and we can not only see the patterns but also feel them with our fingers. This painting technique was also experimented with by the founder back in the day.

‘The bowls, vases, and sculptures coated with this distinctive bluish glaze look as if they have been mysteriously painted with light itself’

It is interesting to note that in the time of Zsolnay, only men worked in the workshop, but then the tables were turned, or rather, times changed, and women took over the brushes. Patterns are designed on paper and then drawn in ink on the object. Next comes the painting, then the firing, and finally the gilding.

Vilmos Zsolnay was born to succeed. He was at once talented and hard-working, stubbornly curious and steadfastly perfectionist. Already as a merchant, he made his store in the centre of Pécs a success. He inherited the shop from his father, and his brother, Ignác, the pottery workshop, which had been moved from Lukafa to Pécs. Over the years, Vilmos helped his brother and the factory several times before he finally took over. He was already over 40 at the time, but he threw himself into the study of chemistry, different technologies, firing techniques, and the properties of raw materials without hesitation. He also saw that, with industrialization and the booming economy, there would be a large and varied demand for ceramics, which meant that there was a good chance of a return on investment.

In addition to tableware, tiles, ornaments, insulating material, pipes, and sanitary equipment were also produced, and there is hardly a building of any significance that was not decorated with elements made at Zsolnay. Pirogranite, a heat-resistant and load-bearing material, was also developed in this period at the Pécs plant.

There was, for example, the butterfly- and the cornflower-patterned dinner service, the same in coffee sets, all at affordable prices. Zsolnay was special because, in addition to its aristocratic and wealthy foreign customers, it always thought of the ordinary person, too. In the last century, there was hardly a household without at least one Zsolnay white bowl or a milk jug, wine bucket, or baking mould from the distinctive pink collection. Here, high quality was matched by an amazing quantity.

In the Pécs factory, large families of several generations worked because there was a secure livelihood and a high level of social welfare. All three of Zsolnay’s children stayed with the company; his daughters Teréz and Júlia were design artists, while Miklós, who was much more bohemian than his father, was a merchant. Zsolnay the Younger was a member of the Upper House, and his decorative buttons were not made of precious stones but of Zsolnay eosin. He did not live to see the nationalization of the factory, which took place during the next generation. The factory regained its legendary name after the fall of communism, and to this day, world-class pieces are produced in the workshops. The old Zsolnay objects are still sought-after items in antique shops and at auctions.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.