The question of what the country’s medieval capital used to be has once again become part of the public discourse in Hungary in recent times. One could, of course, throw in the names of Fehérvár, Esztergom, or Buda at once, but in medieval Hungary, in the sense and similarly to how Prague had developed in the Czech Kingdom, there was no single central seat of the country until the early 14th century. In the Middle Ages the term ‘capital’ was not even known, although medieval people did occasionally speak of a ‘head’, or capital, of the country (from the Latin ‘caput’, meaning ‘head’). In the time of travelling royal courts, the capital was of course always wherever the king travelled to and established his seat, but even so, neither Temesvár (today’s Timișoara, Romania) nor Visegrád on the Danube in the 14th century became a capital proper under the Angevin kings.

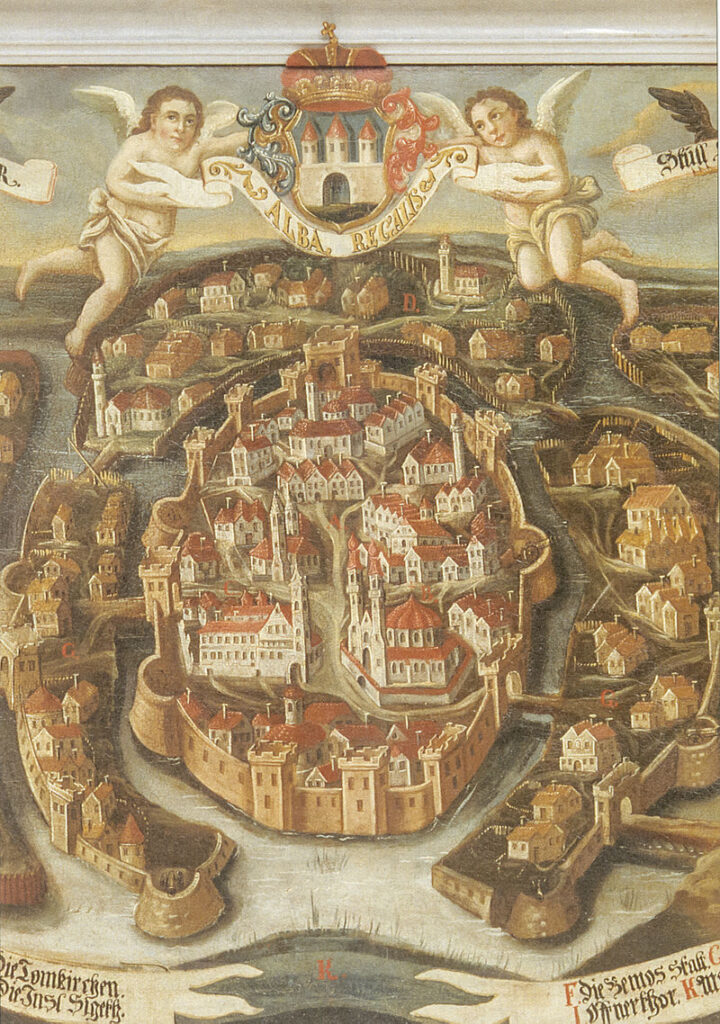

Yet, the connection between the medieval foundation of the state, King St Stephen, and Fehérvár (meaning ‘white castle’), 60 kilometres from Buda, is still inseparable. Even the modern name of the town, Székesfehérvár, in use since the 16th century, is a reference to the royal throne (with the Hungarian ‘szék’ meaning ‘chair’ or ‘throne’). Concerning the royal seat, Fehérvár’s sacral–dynastic character is undoubtedly in its favour: namely, the burial here of the first Hungarian king St Stephen (reigned 1000–1038) and his son Prince Emeric (d. 1031). Both were canonized in 1083, and their tombs became a pilgrimage site of national fame. In the middle of the 11th century the Hungarian annals refer to the city as a ‘metropolis’ (literally ‘mother city’). The royal treasury and coronation insignia (which were temporarily transferred to Visegrád in the 14th century), the national banner of war, the keeping of the royal archives, and the coronation itself made it one of, if not the primary centre of the country. The strategic location of this non-swampy city was also unrivalled; in 1242 the Mongol armies could not capture it either. As early as 1055, a document that has survived in its original form recorded the earliest words written in Hungarian: ‘military road to Fehérvár’. The founder of the city is undoubtedly King St Stephen, and a few years after his coronation the town is also mentioned in several documents. Besides, the opening of the pilgrimage route to the Holy Land by Stephen around 1020 was at least of similar importance. Heading there, the pilgrims passed through Fehérvár, as did the Crusader armies crossing the Balkans to Constantinople and the Middle East.

‘The connection between the medieval foundation of the state, King St Stephen, and Fehérvár is still inseparable’

Following Western patterns can be good or bad. In Stephen’s case, it was an excellent idea to found a collegiate church in Fehérvár, as the more important churches not built in an episcopal seat were called at the time, also bearing the name of the Virgin Mary, modelled on the chapel of the Carolingian monarchs in Aachen. The authority of the Archbishop of Esztergom was undoubtedly damaged by the new foundation, but a similar duality can be observed in Krakow and Gniezno in Poland as well. The chapel, dedicated to the Virgin Mary, was endowed by King Stephen with the treasures he had captured during his campaigns. The new church was not only one of the many churches he built during his reign, but the King also gave it a special role and made it the ‘private chapel’ of the kings of the Árpád Dynasty. With its dimensions of 76 metres long and 30 metres high, the three-nave basilica was one of the most representative European buildings of its time. Little of it can be seen today, however, as the church was unfortunately blown up during the Turkish wars in 1601. At the end of the 18th century parts of the ruined basilica were still standing high, but its stones were used to rebuild the city and only its foundations survived.

However, the King never had his own palace in Fehérvár, since the royal palace was located in Esztergom, the seat of the Hungarian archbishops, until around 1200. Even around 1100, the county governors did not deliver the royal taxes to Fehérvár, but to Esztergom, where mint coinage took place. Unsurprisingly, foreigners were not able to make up their minds about the capital either: when they were looking for the legendary seat of Attila the Hun around 1200, they mentioned both Esztergom and Buda, that is, today’s Óbuda. After all, the city did not become a permanent royal seat, but its cultic and political significance remained the same, and in a sense, it was always considered the ‘centre of the country’. Hungarian common law from the Árpád era, probably as early as the 11th century, only considered the coronation of the founder of the state in the church of Fehérvár. The tomb, the relics of the canonized monarch, his sceptre, and the vestment he had made and turned into a coronation robe were the evident and tangible legacy of St Stephen, in which the Middle Ages found the protective and helping power of the Holy King.

The Holy Crown was kept in the church treasury until the time of King Sigismund, and the most distinguished member of the establishment was responsible for it. It became customary for the kings to hold a national assembly and justice day in Fehérvár around the feast of the canonization of Stephen, 20 August. The custom was later made law by the charters of King Andrew II, the Golden Bulls of 1222 and 1231. Nevertheless, from the end of the 13th century, the Rákos field assemblies near Pest became customary, but sometimes diets were also held here later. In the Middle Ages, the last time a diet was held here was in 1527, the year after the Battle of Mohács, and later in 1938, the festive year of St Stephen.

Comparing medieval towns is very difficult because of their different legal status and the fragmentary nature of written sources. Regarding Hungarian cities, historian András Kubinyi has devised a system that considers a dozen aspects.[1] Among the factors taken into account were the town’s position in the national road network, the number of religious institutions, the number of national and local fairs, the number of students registered at foreign universities, etc. In this comparison, Fehérvár is closely behind Buda and Pressburg (later Pozsony, now Bratislava, Slovakia), on a par with Kassa (now Košice, Slovakia), Kolozsvár (now Cluj-Napoca, Romania), and Szeged.

Obviously, Fehérvár was also intended to be a permanent burial place for the monarch and his family, just like the Abbey of St Denis near Paris for the kings of France. However, this custom was not established until very late, as the idea had not even occurred to the immediate successors of St Stephen. Each of them chose to be buried in a church that he himself had founded and could therefore consider his personal ‘property’. Thus, for example, King Samuel Aba (r. 1041–1044) was buried in the Monastery of Abasár, and King Andrew I (r. 1046–1060) in the Tihany Abbey.

‘Fehérvár was intended to be a permanent burial place for the monarch and his family’

King Coloman was the first to be buried in Fehérvár in 1116, and his example was followed, strangely enough, by King Béla II, who was blinded by Coloman as a child. Béla was then followed by three of his sons, and then by the greatest ruler of the century, the first king to take a crusade vow, Béla III (r. 1172–1196). In the 13th century the kings turned their backs on Fehérvár for good—the basilica became a royal burial place again only under the Angevin Dynasty, but still not once and for all. The first Angevin king, Charles I, restored the fire-damaged basilica twice and chose it as his burial place; there is even a detailed account of his large-scale funeral there in 1342.

Székesfehérvár became the permanent burial place of the Hungarian kings only after the death of King Sigismund in 1437. This fact was certainly connected to the victory of the nobility’s movement in 1439, which was accompanied by the revival of some ancient traditions. Such was the role of Székesfehérvár, as witnessed by its living tradition of coronations. It was at this time, in the middle of the 15th century, that the conviction was formed that the eternal resting place of the descendants of St Stephen could be no other than the Basilica of Fehérvár. Until 1543, when the city and the church fell under Turkish rule, five more kings were buried here, including Matthias in 1490, the last rebuilder of the church, and finally János Szapolyai in 1540. The basilica is thus the resting place of 15 out of 37 Hungarian kings. Only two kings were not buried here between 1437 and 1543: Ulászló I, who fell to the Turks on the battlefield of Varna in 1444, and Ladislaus V of Habsburg, who died and was buried in Prague in 1457. The city was conquered by the Turks in 1543; and the Habsburg kings, who came to the Hungarian throne, were buried in Vienna anyway.

‘The basilica is the resting place of 15 out of 37 Hungarian kings’

Fehérvár remained under Turkish rule until 1688. Over time, the tombs there were destroyed and looted. The only exception was the miraculously intact double tomb found in December 1848, in which the skeletons of a king and queen were discovered. The tomb was conclusively identified as the remains of King Béla III and his first wife, Agnes of Antioch. The remains were transferred in 1862 to the Church of Our Lady of the Assumption in Buda, now Matthias Church. Here, as part of the Millennium celebrations, they were given a decorative burial place with the support of King Franz Joseph of Hungary and were reburied in 1898. The tomb statues were made to the exact size that the skeletons suggest Béla III and Agnes would have been: 192 and 150 centimetres respectively.

Although burial in Fehérvár was mainly reserved for members of the royal house, others were also exceptionally granted this privilege. In 1427 King Sigismund, at his request, allowed Comes István Rozgonyi to choose a burial place ‘for himself, his wife, children, brothers and sisters, and whole kinship’, wherever he wanted in the Basilica of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, as well as to erect an altar there and enrich it with possessions and goods at his discretion. It was the István Rozgonyi, who, a year later, with his warlike wife by his side, fought heroically against the Turks at the castle of Golubac. Shortly before Rozgonyi, King Sigismund’s Florentine-born commander Filippo Scolari, also known as Ozorai Pipo in Hungary, was granted a similar privilege. Besides, King Matthias also buried here his favourite Czech mercenary captain, František Hag, who was killed in 1476 at the siege of the Castle of Szabács (now Šabac, Serbia).

After the expulsion of the Turks, Fehérvár could not regain its medieval importance, and the place of the royal coronation remained Pressburg. This was somewhat compensated for by the foundation of the bishopric in 1777, and then by the gesture of the founding queen, Maria Theresa, who, after the Turkish occupation of Fehérvár, recovered the skull relic of St Stephen, which had been kept in Ragusa (now Dubrovnik, Croatia), and donated it to the basilica.

It was the festive year of St Stephen in 1938 that restored the town to its status as the number one St Stephen’s memorial site. The newly completed ruin garden, the monuments and series of historical frescoes still present today, the dedication of the royal tomb and, last but not least, the extraordinary session of the Parliament here which legislated the national holiday of 20 August made it a unique year in the life of the city. Of course, we still have the opportunity to think about all this today if we visit the Székesfehérvár Royal Days, a series of events having been organized around the feast of King St Stephen since 1996.

[1] András Kubinyi, ‘Székesfehérvár helye a késő középkori Magyarország városhálózatában, valamint Fejér vármegye központi helyei között’, in Gyöngyi Erdei, Balázs Nagy (eds.), Változatok a történelemre: Tanulmányok Székely György tiszteletére, Budapest, 2004, pp. 277–284.

Related articles: