Review of Michael O’Sullivan’s Trianon – Tragedy of a Nation: The Memoirs of Tibor Scitovszky

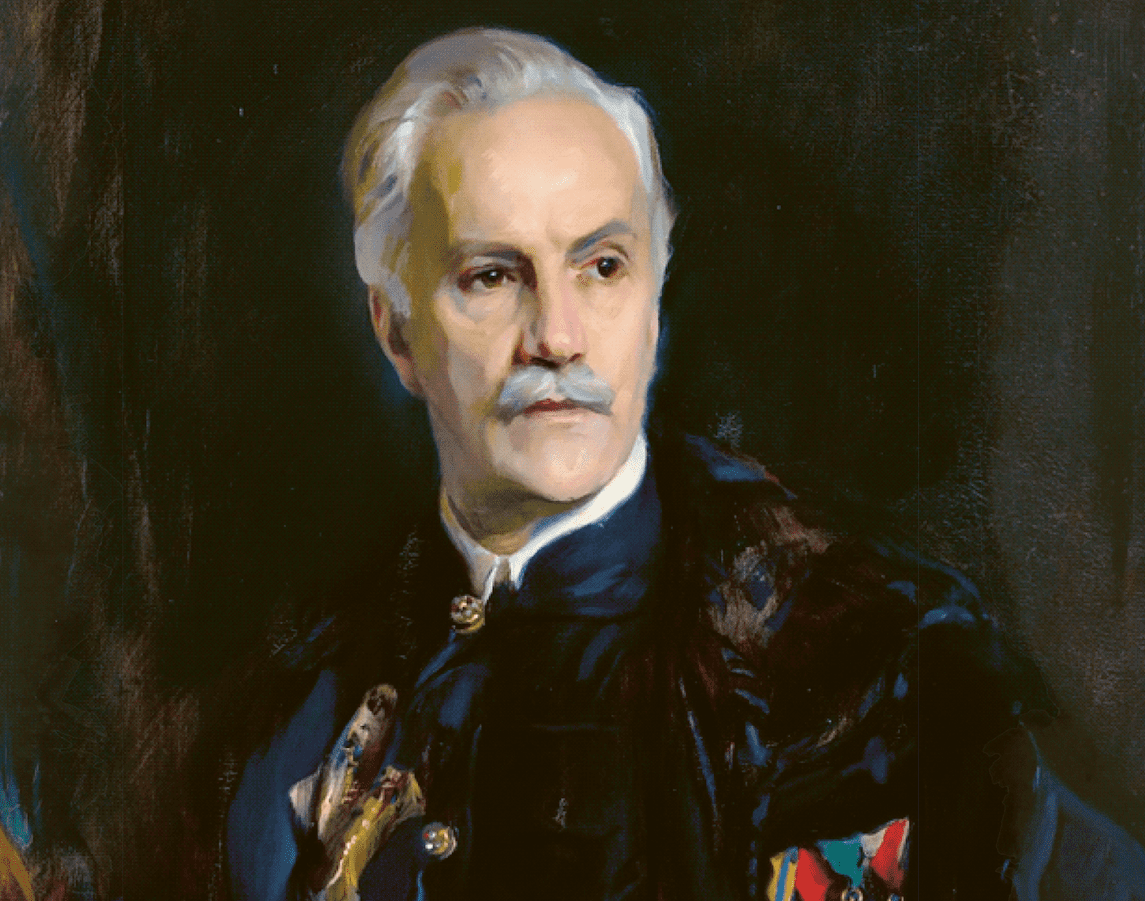

Winston Churchill once said that the price of greatness was responsibility. For most of us who are inclined to think in a more conservative way, this naturally feels right, but we only discover just how true it actually is after reading about the lives of exceptionally great men and women of our past. And the more we do, the more it dawns on us that genuine greatness does not necessarily bring about the widespread admiration of the generations whose lives were improved by the efforts of such people, despite the immeasurable magnitude of the tasks they took up with selfless responsibility. One of the unknown heroes of twentieth-century Hungarian history is Foreign Minister Tibor Scitovszky (1875– 1959), whose recently published memoir is a vivid testimony of unwavering responsibility amidst the harshest of circumstances.

It almost feels like a cliché to say that Hungarian history is nothing but a never-ending series of struggles against insurmountable odds, although this most certainly has been the case at least in the last five centuries. In many ways, that is what gave Hungary its unique character: Hungarians are freedom fighters, unconcerned with the hardships that may lie ahead. However, the key turning points of history are always unique, and call for different solutions: some require a nation to stand up as one, while some only require the presence of a few statesmen who are not only able but also willing to serve a purpose higher than themselves. One such crisis, and perhaps the greatest in our history, was the political and social chaos brought forth by the Treaty of Trianon (1920) upon the smoking rubble of a dismembered nation waiting to be rebuilt again. That is precisely where we find Scitovszky, navigating through the subtleties of interwar diplomacy.

This work is meant to be the retelling of the enormous efforts put forward by a handful of great men, and not one, to save a country that already seemed to have gone over the precipice

He does not start his account by telling readers just how devastated Hungary was in that period—everybody knew it at the time of writing (the late 1950s), and his humble character repeatedly drove him to underplay his own role in events, lest he be accused of boasting. He did not seek admiration or gratitude—this work is meant to be the retelling of the enormous efforts put forward by a handful of great men, and not one, to save a country that already seemed to have gone over the precipice. That is why this book also contains an excellent introduction written by the historian Tamás Barcsay to explain Scitovszky’s Hungary for those of us who can only imagine it. To explain the realities of a broken nation, occupied by several foreign armies, plagued by civil war, unspeakable inflation, famine, and endless waves of refugees, denied of not only fair representation by Western powers, but all sympathy and hope as well.

Scitovszky himself was no ordinary man, of course, as he belonged to those few who never let themselves be broken by the dreadful realities of the post-war years. Coming from a family of Polish origin which was ennobled in the nineteenth century, he was born into a society of great wealth and influence, and also—characteristic of Hungarian nobility of the time—of an inherent sense of patriotic responsibility which ultimately shaped the history of our nation. He met Count István Bethlen—the future prime minister of Hungary and perhaps the most notable one to ever occupy that office—when they were young boys studying together in the Viennese Theresianum, and their friendship lasted through the decades as the two men served together in the Hungarian delegation to Versailles, and continued to do so later in the Hungarian government.

The memoir itself follows the events of this second ‘nation-building’ from quite a professional angle. Scitovszky barely touches on anything related to his personal life; his accounts are strictly about matters of state, starting from the restoration of public order in the country, through the humiliating peace process that took place in Paris, to the constant negotiations and positioning that followed in the consistently hostile international environment Hungary had to face throughout the 1920s. All the events are shown through the eyes of a born statesman: a sense of unmoved calmness accompanied by polite objectivity in his observations, interwoven with remarkable reasoning at every step. Through Scitovszky’s words, one not only peeks into the secretive world of interwar diplomacy through the keyholes of heavy salon doors thick with the scent of cigars and champagne, but also learns why it was all bound to happen as it ultimately did—and how, given the circumstances, the fate of Hungary was in the most able possible hands.

On the rare occasions when Scitovszky does let his emotions break through his generally reserved manner, it is generally when he feels his sense of honour insulted. These lingering grievances come up, in particular, through the detailing of the events around Trianon. For instance, at one point he writes:

‘[I]t should be first of all noted that this term, “peace negotiations”, is entirely false and misleading. No negotiations ever took place, since the peace conditions have already been fixed before the formal “negotiations” began. This was not peace but military subjugation in the crudest possible sense of the term. The condemned were to be denied even the most primitive right: the right to say a word in one’s own defence before judgment is passed.’1

The Hungarian delegation was indeed only invited to sign the treaty—without having been given any opportunity to have a say in it, even though the delegation was led by Count Albert Apponyi, ‘one of the most significant and cultivated politicians in Europe’, who was also ‘uniquely eloquent’ in all major languages of the time.2 In contrast, the representatives of the successor states—to whom two thirds of the territory of the country were eventually granted—had been attending lengthy meetings with all Allied leaders throughout the previous year. An anecdote from a later event, that took place after a conference between the Hungarian and Czechoslovak governments (with the latter’s delegation led by the former chief negotiator and then president Edvard Beneš) in Austria, illustrates Scitovszky’s sentiments towards this injustice perfectly:

‘It was in this [more informal] context, during our discussion in Bruck an der Leitha, that [Beneš] boasted, in a moment of thoughtless honesty, that his success had largely been down to his proficiency in foreign languages: he had been able to speak to all major leaders of the great powers in their own native tongues. […] Count Apponyi, alas, though possessed of the same gifts, was unable to arrange face-to-face meetings with any of the leading Allied powers—all requests of such meetings were made contingent upon us first signing the treaty and accepting its provisions in full.’3

The years following the signature of the treaty found Scitovszky travelling from one conference to another, struggling to alleviate the effects of the disastrous conditions forced upon Hungary with two main motivations in mind: to break his country out of the crippling political and economic isolation imposed by the West and kept in place by the so-called ‘Little Entente’ of neighbouring countries, and to ensure equitable treatment for the millions of Hungarians who suddenly found themselves citizens of the successor states. The former was undoubtedly the more crucial of the two and it took a decade of marvellous diplomatic and financial manoeuvres— most of which were primarily carried out by Scitovszky himself, as director of the Hungarian Credit Bank in the late 1920s—to gradually begin pulling Hungary out of the economic wilderness it had been cast into.

The second task, regarding the treatment of minorities, proved considerably harder than was at first imagined by Scitovszky and his colleagues, who—being ardent supporters of Wilsonian principles—had perhaps put too much trust in the international community. After being appalled when they learned how little the term ‘self-determination’ meant for the West when dealing with Hungary at Trianon, they were continuously reminded of the same at subsequent conferences, where they were denied the possibility of plebiscites outside the borders—with the sole exception of the city of Sopron, which voted overwhelmingly to return to Hungary. Nor was the League of Nations moved by the dozens of memoranda written by the Hungarian foreign ministry, detailing the countless acts of systematic discrimination the new Hungarian diaspora had to face. The words of Count Apponyi (quoted by Scitovszky) are particularly telling in this regard:

‘“There is no other conservative politics for the League besides the politics of the fait accompli. Only when the League discovers the courage to uphold the fundamental principles of international law will it be possible to forge true, lasting, amicable peace. But”, he went on, with a resigned sigh, “I greatly doubt whether I shall live to see that day.”’4

Apponyi’s remark stands true to this day, unfortunately. The leaders of the international community—and the very organizations charged with upholding fairness and justice in it—have never seemed particularly concerned about national minorities, even though the direct precursor to the United Nations—Wilson’s League of Nations—was created precisely for that reason. Nonetheless, what seems a commonplace now had to be learned the hard way by these Hungarian delegates, namely that political interests always take precedence over the idealist values we like to place our faith in. So, in the end, the enormous effort Scitovszky had put into trying to amend the situation of the Hungarian diaspora produced little to no results. But after detailing the numerous meetings and debates he had (while reasonably pointing out the more sensible aspects of the minority question), he ends the chapter in a way that is most expressive of his noble character and exceptional statesmanship:

The leaders of the international community have never seemed particularly concerned about national minorities, even though the direct precursor to the United Nations was created precisely for that reason

‘I have no wish, however, to lose myself in the maze of particularities which this topic always throws up, and would rather concentrate on seeking the basis for some future reconciliation and mutual understanding among the multifarious peoples who inhabit the lands of the vast Danube Basin. Equally, I have no desire to enter into a long discussion of the bitter alienation of former friends, or of friendly and mutually supportive nations, entailed by the Treaty of Trianon. When dealing with minority populations, may wisdom and moderation ever reign!’5

In its entirety, Scitovszky’s memoirs are a compelling and eloquent retelling of many of the obscure events at and after Trianon, written by a man of a sophisticated age, hardened by insurmountable challenges and driven by a sense of duty and responsibility. However, while he paints a grim picture of those years, his accounts are also full of life, admiration towards his peers—regardless of which side of the table they were sitting on—and even some truly charming anecdotes.

For instance, Scitovszky details in length how the Romanian Foreign Minister Nicolae Titulescu easily won the hearts of a room full of high-society Parisians by proving to be an excellent connoisseur of French champagnes (‘after a single taste, he was able to identify not only the producer but even the year’6); or the time when the Italian Foreign Minister Count Dino Grandi was left fuming after an evening in London, where one guest was convinced he was in fact Mahatma Gandhi and kept treating him as such (‘she complained to the host that she had continually tried to talk to her neighbour about India, but that Mr Gandi—as she pronounced the name—did not appear to know the first thing about the place!’7). These luxurious dinners and splendid receptions were just as significant a part of diplomatic missions as any other in Scitovszky’s time, and his memoir does not fail to show them—and their political importance—in the usual manner of humble expertise:

‘[E]ven the most delicate matters can be discussed more easily—sometimes perhaps even solved—over white tablecloths, and in an atmosphere of generous hospitality, than over the green baize of a formal negotiating chamber. Tongues are loosened at a dinner party, and matters come up which might otherwise have remained unspoken.’8

We must also note that the greatness of Scitovszky’s character and his timeless lessons about honour, justice, and statesmanship could have never reached Anglo-Saxon readers without two Irish gentlemen. First, the author’s proficiency as an eloquent writer could not have been presented in this book without a translator of similar skill and competence (as the memoirs were written in German, the historical lingua franca of the Hungarian nobility), and Thomas Sneddon did a wonderful job in this regard. The other is, of course, Michael O’Sullivan, to whom all of Hungary is indebted for taking up the task of publishing this invaluable volume in English and who, as the editor of the book, made sure it remains a truly enjoyable read by adding explanatory notes for the nearly one hundred important people whose names appear in the text.

The political generation of Tibor Scitovszky took responsibility for a country when not many would have done so, given the circumstances, and gave the nation reason to feel proud again

Scitovszky’s memoir is a marvellous period piece which gives a vivid description of the most important politicians, events, and the general atmosphere of his time, while also proving Churchill’s view of greatness true in all respects. The political generation of Tibor Scitovszky took responsibility for a country when not many would have done so, given the circumstances, and gave the nation reason to feel proud again. They paid with their own lives for their bravery: some in a literal sense (such as Prime Minister Pál Teleki, who took his own life to protest the way Hungary was being dragged into the Second World War), while some were forced to flee the country they had sacrificed everything for to avoid imprisonment, torture, or even execution at the hands of the Nazis or the Communists. Scitovszky himself, as a life-long, unwavering democrat and fearless critic of totalitarianism, knew precisely that his time in Hungary had come to an end when the Nazi occupation of Budapest began, but he managed to find his way to the United States where he continued to live as one of the most renowned economists of his time.

In Hungary, nonetheless, he will always be remembered as one of the great men who founded modern Hungary in the wake of the disaster of Trianon. Their courage and perseverance had borne fruit in the end, and— through memoirs such as Scitovszky’s—they continue to serve as an example for countless generations to come. All we could ever wish for when our journey comes to an end is that we will be able to accept our fates with the humble equanimity of Tibor Scitovszky:

‘I have no intention of claiming this gradual escape from isolation as my own doing, and I willingly accept that […] external factors were decisive. Still, it is a source of satisfaction to me that in the time of greatest peril for Hungary, I was able to play some role in allaying these dangers to my country.’9

NOTES

1 Michael O’Sullivan, ed., Trianon – Tragedy of a Nation: The Memoirs of Tibor Scitovszky (Budapest: Hungarian Review, 2020), 24.

2 O’Sullivan, Trianon, 17.

3 O’Sullivan, Trianon, 120–21.

4 O’Sullivan, Trianon, 40.

5 O’Sullivan, Trianon, 53.

6 O’Sullivan, Trianon, 94.

7 O’Sullivan, Trianon, 116.

8 O’Sullivan, Trianon, 94.

9 O’Sullivan, Trianon, 98.