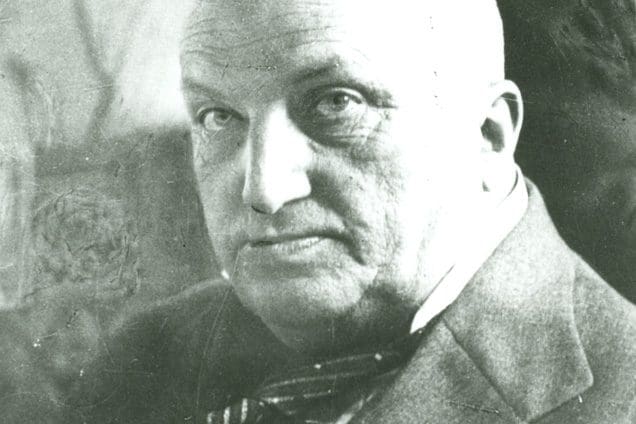

The fundamental tenet of Dezső Szabó’s thinking was the view he expressed in his 1915 essay ‘The Failure of Individualism’, published on the pages of the bourgeois radical, left-leaning Huszadik Század (‘Twentieth Century’) journal. According to this study, individualism that promotes individual prosperity and material self-realisation, as well as liberalism that gives birth to it and its economic system, capitalism, is about to fail in the face of the ‘liberating’, ‘primitive, cruel wild instincts’ of the twentieth century. According to him, the opposite of these—social sensitivity, collectivism and anti-competition— will be the watchwords of the next century.[1]

Szabó’s views on antisemitism—or rather, his early support for it—cannot be separated from his criticism towards capitalism. In this respect, his position was very similar to that of the bourgeois radical Oszkár Jászi, himself of Jewish ancestry, who also identified the Jews as one of the pillars of the dualist system of large landowners and big capitalists. Jászi therefore attacked the adherents of his former faith with such glee that, according to historian János Pelle’s apt formulation, his writing could be mistaken for far-right propaganda.[2] However, Dezső Szabó was not bothered by the common ground, in fact, he was particularly proud of it: ‘I bash the Jew. Oszkár Jászi also bashes the Jew. And this is a collaboration that reassures me,’[3] he wrote in Huszadik Század. Originally from Transylvania, Szabó involuntarily reveals the roots of his anti-capitalism in his novel Elsodort falu (‘A Village Swept Away’), when he writes about the plight of Hungarian intellectuals living in the countryside, destined for greatness, but mercilessly sidelined by their Jewish competitors. Despite the fact that he was endorsed by the Jewish press magnate Lajos Hatvany (originally Deutsch) in Budapest, Szabó showed little gratitude towards his own stereotypical ‘Jewish capitalist’. According to an anecdote from the end of the ‘revolutionary’ months of 1919, before he left Hatvany’s house, where he was staying as a guest, Szabó called the servants together, and told them to set fire to ‘Comrade Deutsch’s’ apartment.[4]

The left-wing press in later years treated Szabó as a kind of ‘anonymous socialist’

However, the anti-capitalist interpretation of his book was already made by his contemporaries. The young socialist Pál Ignotus saw an anti-big-estate miracle in Elsodort falu,[5] and Bálint Aladár, the critic of Népszava, published his laudatory opinion of the book even during the communist Republic of Councils of 1919.[6] The artist turned communist Ödön Palasovszky and the Octobrist (that is, supporter of the bourgeois revolution of 1918) Károly Molter similarly praised the book’s revolutionary spirit (the latter highlighted the book’s ‘strikingly anti-elitist’ character).[7] The left-wing press in later years also treated Szabó as a kind of ‘anonymous socialist’ (for example, in 1926 the Socialist daily Népszava lauded the book as ‘the most powerful Hungarian novel of the century’).[8] And Szabó himself agreed with all of this, even if he only accepted the label socialist (or rather ‘social democrat’) in 1913, while later he rejected it. However, during the brief 1919 communist rule, he wrote as follows to Imre Kner, head of a famous publishing house:

‘This novel is a thousand times more revolutionary than the (Octobrist) National Council; it is its programme, completely and expressly, and not only that! It demands the rights of the people even against the revolution. Based on the programme, in order to ensure equal access to life for all races, it dares to speak brave and true words against the Jewry, precisely against racial bias, financial imperialism and ancient superstitions. This is a necessary criticism of that race, which, if it did not exist, would need to be produced chemically here, but which must be saved from its own sins and from being the pillar of an arrogant, biased money-feudalism’.[9]

When Dezső Szabó finally turned on the Jewish intellectuals of his era, his ‘conversion’ was loudly celebrated by the ‘counter-revolutionary’ right-wing press. They really had nothing to celebrate: Szabó had already published antisemitic articles before, and his idea of capitalism had not changed in the slightest since he had loudly called himself a communist. What is interesting is that his left-wing friends, prior to his right-wing turn, did not notice that he was an anti-capitalist who also happened to be an antisemite. In the words of literary historian Antal Babus: ‘Before Dezső Szabó joined the Christian system, the left-wing accepted him and his novel. Under the communist period of 1919, they saw him as a critic of the previous dualist system and an author who regularly published in Huszadik Század. They thought he was a raving ally and refused to notice his peculiarities’.[10]

It is necessary to note, however, that Szabó broke with the right-wing Horthy system by 1923 and remained its critic until his final days during the siege of Budapest. Szabó also sharply criticised the pro-Nazi Arrow Cross Party in his late years (we will write more on that later), but here we only had space to explore his views on capitalism (and his antisemitism connected to it) during the years immediately following Hungary’s defeat in the First World War and Trianon. Dezső Szabó was not only a nationalist, but also a strong opponent of capitalism during his entire life. The fact that this was hidden by socialist historiography only shows that many more myths have to be debunked by the Hungarian historians of today.

[1] Dezső Szabó, ’Az individualizmus csődje’, Huszadik Század, 1915/8, 81-94.

[2] János Pelle, Jászi Oszkár, Martonvásár, Kairosz, 2001, 229.

[3] Dezső Szabó, ’A magyar zsidóság organikus elhelyezkedése. Nyílt levél a Múlt és Jövő szerkesztőinek’, Huszadik Század, March 1914. 60.

[4] Péter Nagy, Szabó Dezső az ellenforradalomban, Bp., Szépirodalmi, 1960, 12.

[5] Pál Ignotus, ’Csipkerózsa’, Haladás, 29 May 1947.

[6] Aladár Bálint, ’Új könyvek. Szabó Dezső. Az elsodort falu. Regény két kötetben’, Corvina, 20 July 1919. 107-108.

[7] Ödön Palasovszky, ’Az elsodort falu’, Ifjak Szava, 30 Nov. 1919, 13-14, and Christmas 1919, 28. See also: Károly Molter, ’Szabó Dezső: Az elsodort falu’, Zord Idő, 16 Oct. 1919, 126.

[8] Népszava, 24 Feb. 1926, 11.

[9] Imre Kner, A könyv mestere, Budapest, Helikon, 1969, 36.

[10] Antal Babus, ’Fülep Lajos az 1918-1919-es forradalmakban’, Új Forrás, 2002/7, 62-82.