When Pope Francis visited Budapest, he was visiting the capital of a historically Catholic country, though one in which the Christian faith is held, but scarcely practised.

According to a 2017 Pew Research Center survey, Hungary is one of the most secular countries in Central and Eastern Europe, with only 9 per cent of its people reporting attending church services weekly. Pew found that 64 per cent of Hungarians ‘seldom or never’ go to church.1 The numbers are even more dire among young people aged 16 to 29. An analysis by St Mary’s University (London) sociologist of religion Stephen Bullivant, based on data gathered from 2014 to 2016, found that 67 per cent of Hungarians in that age cohort identify with no religion, and only 3 per cent go to weekly Mass.2

In the nearby Czech Republic, the picture is even darker, with only 3 per cent of Czech Catholic youth going to Mass weekly, and a staggering 91 per cent of the Czech youth professing no religion.3 As a young Czech priest once told me, ‘I will probably live long enough to bury Christianity in my country’.

Poland is the great regional exception. According to the 2017 survey, 41 per cent of Catholics there go to church weekly, with only 19 per cent seldom or never darkening the door of their parish church.4 But there have been stark changes in the four years since that survey was taken. Conditions for Catholicism in Poland, the home of Pope St John Paul II, and long considered a bastion of the faith, have weakened in the wake of shocking revelations of clerical sexual abuse and episcopal cover-up. Last year, the Polish Episcopal Conference announced a yearly decline of 1.3 per cent of weekly mass goers, bringing the four-year falloff of the nation’s Catholics to four per cent.5 Given the angry national fallout over the church’s support for very strict new abortion regulations, that number is likely to decline further this year.

Worryingly for church leaders, polls last fall and winter revealed that more Polish Catholics distrust their church than trust it. Huge pro-choice protests across Poland last autumn, following the Constitutional Court’s abortion ruling, took a distinctly anti-Catholic tone. Protesters defaced churches with graffiti, and spray-painted phone numbers on sidewalks where pregnant women could phone to get abortion pills. In Kraków, under the balcony where John Paul II once blessed the faithful, demonstrators chanted, ‘F—k the priests!’

The poll numbers among Poland’s Catholic youth are close to catastrophic for the church. A 2019 survey by the Centre for East European and International Studies, conducted before the protests, showed that two thirds of the Polish youth either barely trusted the church, or did not trust it at all. Of all the institutions in Polish life, the church is one of the least trusted among the young.6 A 2017 Pew poll found that 23 per cent fewer young Poles said that religion is important in their lives than older ones—the greatest generation gap in all the 45 countries surveyed.7 (The disparity in Hungary between youth and adults is only 9 per cent, but that is because the number of religious Hungarians is already small compared to Poland.) These Polish statistics confirm anecdotes I have heard on reporting trips to that country over the past two years.

A number of young conservative Catholics, in both Warsaw and Kraków, told me that they fear their country could soon go the same way as Ireland, and experience a sudden near-total collapse of the Catholic faith

As a middle-aged American who came of age in the era of Pope John Paul II, I found this difficult to believe. Then, on a 2019 visit to Poland’s famed Tyniec monastery, I spoke to a widely respected Benedictine, Father Włodzimierz Zatorski, and asked him if it could possibly be true. ‘Yes, it is’, he confirmed. When I asked him to explain why, he said the main cause is ‘the vainglory of the bishops’. Father Zatorski, who died of COVID in December 2020, meant that the Catholic bishops were too prideful and too blind to see what was happening in Poland. Indeed, Marcin Kaczmarek, an academic sociologist, told Agence France-Press that the decline in confidence in the church had more to do with the bishops’ reaction to the abuse scandal than with the abuse itself. That is, church leaders have a false sense of the security of their own authority.

Stephen Bullivant, an English sociologist of religion, told me that the religious engagement of the youth is the most important predictor of the future of a religion. Cultural Christianity, he said, does not get passed on to the next generation. Either the next generation will be intentionally Christian, or it will not be Christian at all. In the United States, Christianity is in collapse among the so-called Generation Z (those born between 1995 and 2010) because their parents wrongly believed that cultural Christianity would be sufficient. A profession of faith, if one does not practice it, remains ephemeral, and that faith is unlikely to withstand secular pressure.

Given that European Protestantism is in a position as bad or worse than that of European Catholicism, it is all but impossible to be optimistic about the future of Christianity in what was once the heart of Christendom. Optimism, no—but there is reason to hope.

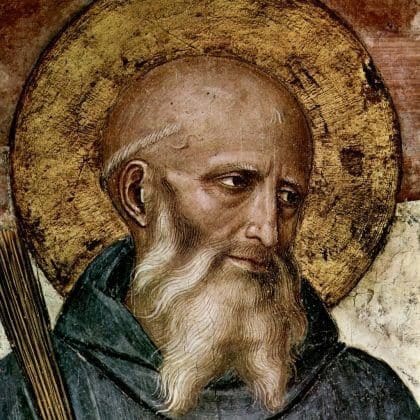

As the Western Roman Empire’s calamitous fifth century turned into the sixth, a young Christian student from the mountains of Umbria, Benedict of Nursia, left his studies in the city of Rome, and retreated to the countryside. The Empire had fallen to barbarian rulers, and Benedict saw so much chaos, immorality, and unbelief in the city that he feared the loss of his own faith if he remained there.

Benedict spent three years living in a cave in the side of a mountain near Subiaco, in a steep and gloomy valley north of Rome. While there, he prayed and fasted, seeking God’s will for his life. He developed a reputation for holiness, and eventually became abbot of a monastery. Benedict wrote his Rule—a guide for Christians living in vowed community. When he died in 547, Benedict left behind thirteen monasteries, and his Rule. Over the next few centuries, Benedictine monasticism spread like wildfire across Europe, which was roiled by great turmoil and suffering in the wake of Rome’s fall. The monasteries became oases of light and order amid the darkness and chaos of the early medieval period. Those early Benedictines taught the faith to the peasantry, but also instructed them on how to do simple tasks—like winemaking and metallurgy—the knowledge of which had been lost in the catastrophe. And in their libraries, the monks kept alive the cultural memory of Greco-Roman civilization. Over centuries of patient struggle, the Benedictines laid the groundwork for the rebirth of civilization in Europe. This is why the Catholic Church regards Benedict of Nursia as one of Europe’s patron saints.

What does Benedict’s legacy have to teach Christians today? This is a question I explore in my 2017 book The Benedict Option, which was recently released in a Hungarian translation.8 I am convinced that if Christianity—not only Catholicism, but all forms of Christianity—is to have a future in the secularizing West, it will have to be Benedictine. That is to say, it will have to be built around an intentional, disciplined, and communal practice of the faith. No, the laity will not need to build monasteries. But it will need to develop new and more focused ways of living out the traditional faith together. That means the laity will also need to back away from the secular mainstream in some ways, to strengthen its own sense of itself as disciples of Christ. This is not, as some critics have alleged, a counsel to ‘head for the hills’. Rather, it is simply to say that in this post-Christian culture, ordinary believers face the same dilemma that St Benedict did around the year 500: to remain fully engaged with the world is to risk losing the faith entirely.

Consider the three Hebrew youths— Shadrach, Meshech, and Abednego—in the Book of Daniel. Though enslaved by the Babylonians, they were advisers to King Nebuchadnezzar. It is hard to become more embedded in Babylonian society than that. Yet when Nebuchadnezzar ordered them to bow down before an idol, the three men chose the prospect of a terrible martyrdom in a furnace rather than apostatize. God, of course, miraculously saved them—but had He not done so, their sacrifice would still have been exemplary.

What latter-day Christians need to ask ourselves is this: how did those three Hebrew men live in Babylon prior to their testing that enabled them both to recognize that they could not apostatize, and to find the strength to choose death before abandoning God? Or, to bring the point up to date, why is it that in the tiny Austrian Catholic mountain village of Sankt Radegund, farmer Franz Jägerstätter was the only believer who refused to collaborate with the Nazis? Why was he the only one who both recognized Hitler as an antichrist, and was prepared to die before swearing an oath to him? Jägerstätter was executed by the Nazis, and beatified as a martyr in 2007. In the 2019 film A Hidden Life, based on Jägerstätter’s own life story, the fictional Franz visits an artist painting Biblical images on the walls of the local church. He tells Franz that Jesus has lots of admirers, but that He did not call admirers; Jesus called disciples. You can only tell the difference, said the artist, when you are called to suffer for Jesus.

The only Christians whose faith will survive what is to come will be those who know how to suffer for Jesus. And the only ones who do that will be those who have been living lives of authentic discipleship prior to the time of testing. That means regular prayer, churchgoing, fasting, and a vigorous family and community life immersed in the faith. There is no substitute.

This is what is being done right now in a small Italian seaside city called San Benedetto del Tronto. There, a cheerful confederation of Catholic families who cheekily call themselves the Tipi Loschi (which means ‘the usual suspects’) come together around a clubhouse for occasional Mass, for catechesis, sports, gardening, communal meals, and other activities. They have their own private school, the Scuola Libera G. K. Chesterton, where they educate their children according to a traditional model. They all live in their homes scattered throughout the city, and go to their normal parishes on Sunday. But they know that the only way their faith will survive is if they live countercultural. Similarly, a handful of faithful families around Nursia (Norcia in Italian), the home of St Benedict, have recently moved there to raise their children in the vicinity of the town’s monastery. In France, two entrepreneurial young Catholics have started a company, Monasphère, to create ways to allow Catholic families to leave the cities and settle around monasteries. So far, 1,000 French Catholic families have signed up, and thirty-two monasteries have agreed to participate. Before his untimely death last year, Father Zatorski, the Polish Benedictine, founded Opcja Benedykta, dedicated to building a hermitage where both clergy and lay Catholics can live in a strong, intergenerational Christian community.

Some critics of these Benedict Option initiatives say they violate Pope Francis’s wish that Catholics today go ‘to the peripheries’ in search of converts. It is certainly true that Christians must evangelize, always, yet it is also true that if the centre does not hold, there will be few believers to take the Gospel to the peripheries. After all, you cannot pass on what you do not have. While not neglecting evangelism, European Catholics must prioritize discipleship in their own families and communities. To do otherwise, says Stephen Bullivant, is to foolishly pay more attention to bandaging a cut than to stem a haemorrhaging artery.

Though the United States remains a much more religious country than those in Europe, in my travels throughout both Central and Western Europe, I have been surprised and encouraged by the pockets of faith I have seen among young Catholics. In fact, I see more hope in Europe than in my own country. That is because in America, despite the sharp decline of religion among Generation Z, the faith is still much more prevalent than in Europe—and this conceals the fundamental crisis facing US churches. We American Christians still have not begun to grapple with the de-Christianization of our culture. Europeans, by contrast, have been living with this for several generations, and therefore have a more realistic understanding of the situation facing believers.

Moreover, in my experience, European Christians aged forty and under are on balance more in touch with reality than older ones, who still seem to harbour hope that the Church is relevant to broader European society. In my experience, young Christians who still attend church have no such beliefs, and are therefore confident in their countercultural identity. The question they have is not ‘how do we make the faith relevant to post-Christian society?’ but rather ‘how do we live as faithful Christians in post-Christian society?’

This is not to say that they do not want to evangelize. Rather, they see the Benedictine model as more promising. The founders ofMonasphère, Damien Thomas and Charles Wattebled, told me that they want simply to create local communities in which young people can be formed as real apostles, and can evangelize their towns simply by the way they live their lives as believers. The two men have absorbed the fundamental Benedict Option lesson: that in order to be for the world who Christ calls us to be, contemporary Christians must live in some sense away from the world. There is no substitute for personal conversion, spiritual discipline, and building the structures and habits that sustain the faith within small communities. Absent that, Christians will become fully assimilated to the post- Christian world, and will live out the saying of Jesus, when he called his followers ‘the salt of the earth’. The Gospel of Matthew records Jesus’s warning: ‘But if the salt loses its saltiness, how can it be made salty again? It is no longer good for anything, except to be thrown out and trampled underfoot.’ Catholics gathered in Budapest to hear Pope Francis would do well to consider the voice of his predecessor, Benedict XVI, from a radio broadcast he gave back in 1969, when the crisis facing the Catholic Church was not nearly as obvious as it is today. Father

Ratzinger told his listeners that ‘the real crisis has scarcely begun’. What was coming, he prophesied, was the loss of wealth, power, status, and members. It would be a kind of apocalypse. And after that? Here is what Benedict XVI said the future held:

‘The Church will be a more spiritual Church, not presuming upon a political mandate, flirting as little with the Left as with the Right. It will be hard going for the Church, for the process of crystallization and clarification will cost her much valuable energy. It will make her poor and cause her to become the Church of the meek. The process will be all the more arduous, for sectarian narrow-mindedness as well as pompous self-will will have to be shed. One may predict that all of this will take time. The process will be long and wearisome as was the road from the false progressivism on the eve of the French Revolution—when a bishop might be thought smart if he made fun of dogmas and even insinuated that the existence of God was by no means certain—to the renewal of the nineteenth century. But when the trial of this sifting is past, a great power will flow from a more spiritualized and simplified Church. Men in a totally planned world will find themselves unspeakably lonely. If they have completely lost sight of God, they will feel the whole horror of their poverty. Then they will discover the little flock of believers as something wholly new. They will discover it as a hope that is meant for them, an answer for which they have always been searching in secret.’9

This is the hope of European Christianity. When Father Ratzinger became pope in 2005, he took the name of the saint who was a seed planted in a tiny hole in the side of a rocky mountain, in the shadow of civilizational collapse. From the faith germinating inside the heart of the hermit Benedict came the light that ignited a religious revolution in Europe, one that beat back the darkness of unbelief. It happened once. It could happen again. God is always ready to send us what we need. The question is whether we are able to receive it.

NOTES

1 https://www.pewforum.org/2017/05/10/religious- commitment-and-practices/.

2 https://www.stmarys.ac.uk/research/centres/ benedict-xvi/docs/2018-mar-europe-young-people- report-eng.pdf.

3 https://www.stmarys.ac.uk/research/centres/ benedict-xvi/docs/2018-mar-europe-young-people- report-eng.pdf.

4 https://www.pewforum.org/2017/05/10/religious- commitment-and-practices/.

5 https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/46879/ catholic-church-in-poland-records-13-fall-in-sunday- mass-attendance-in-2019.

6 Félix Krawatzek, ‘Youth in Poland: Outlook on Life and Political Attitudes’, ZOiS Report, 4 (2019), https://www.zois-berlin.de/fileadmin/media/ Dateien/3-Publikationen/ZOiS_Reports/2019/ZOiS_ Report_4_2019.pdf.https://www.pewforum.org/2018/06/13/young- adults-around-the-world-are-less-religious-by-several- measures/.

8 Rod Dreher, The Benedict Option: A Strategy for Christians in a Post-Christian Nation (New York: Sentinel, 2017). In Hungarian see: Szent Benedek válaszútján (Budapest: Osiris, 2021).

9 https://www.catholiceducation.org/en/religion- and-philosophy/spiritual-life/when-father-joseph- ratzinger-predicted-the-future-of-the-church.html.