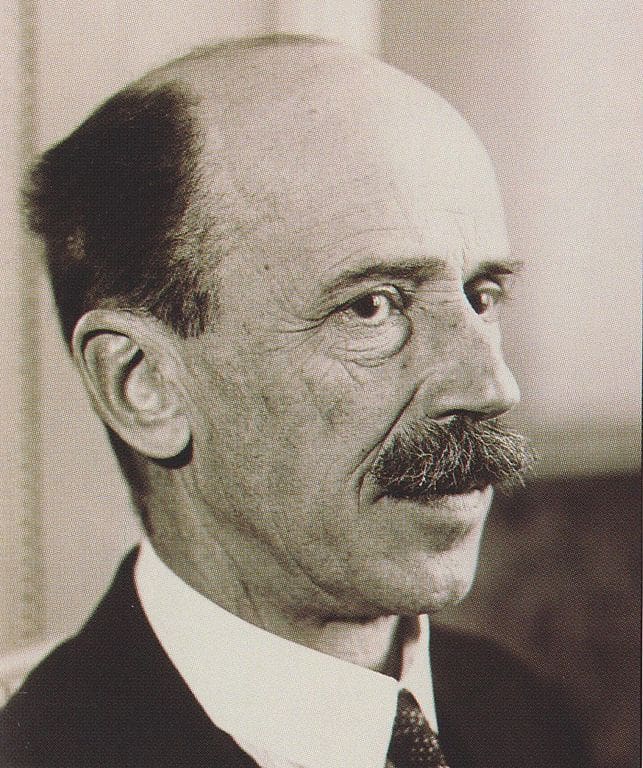

István Bethlen was the most influential figure in 1920s Hungary. Many historians argue that, instead of Regent Miklós Horthy, the era ranging from 1919 to 1944 should be named after Bethlen.

His legacy is highly debated and divisive. However, interestingly, in his case, critical voices are much more muffled than in that of Tisza. Maybe this is the case because he was not shunned by progressive intellectuals of his time, or because he was followed by Gyula Gömbös, who was much more authoritarian and radical. Despite this, during the Communist regime, Bethlen was still described as a ‘proto-Fascist’ and far-right.

Early Years

Bethlen was born in Gernyeszeg, Austria-Hungary in 1874, to a Calvinist and Transylvanian aristocratic family. He studied in Vienna, at the Royal Hungarian University of Sciences (today’s ELTE University). In 1897, he started to practice as a lawyer. At the turn of the nineteenth century, he also got involved in many other, miscellaneous activities.

He took part in a short-term university programme, studying agriculture, and started to manage his family’s estate. Furthermore, he also completed his compulsory military service, and served as a deputy in the county assembly of his home region. Finally,

in 1901, he was elected to Parliament, on a Liberal Party ticket.

From 1901 to 1939, he was a continuous member of the lower house, with the exception of a short break between 1919 and 1921. He was also a member of the upper house until 1944.

His political career was mostly without rupture between 1901 and 1919. However, the Soviet Republic of Hungary caused a brief break in it, forcing Bethlen into exile in Austria. There, he took an active and leading role in anti-Communist organizations. After the ousting of the Communists from power, he was able to return to Hungary.

In 1921, he was elected prime minister.

The Political Views of Bethlen

Bethlen was one of the most characteristically conservative politicians of early nineteenth-century Hungarian political life.

While starting out as a deputy of Tisza’s Liberal Party, his real political home was in the United Party, the party of power in the Horthy era, which he founded in 1922. Bethlen was also a leading figure in the agrarian movement, which supported free trade, and opposed radical land reform, in order to bolster the interests of large landowners. Furthermore, he was one of the staunchest advocates of Transylvanian Hungarians. He recognized the silent expansion of Romanian ‘soft power’ in the region during the early 1900s and called for more state support to Hungarian farmers, and for a settlement policy on abandoned lands.

Bethlen defined himself as ‘Christian and national’,

which label became the official ‘brand’ of the Horthy era. He was a monarchist, although held mixed views on the Habsburgs. Bethlen opposed both Nazism and Communism. While he had sympathy for Mussolini, Bethlen was much more moderate—being a moderate on issues was one of the most defining characteristics of his political persona. His premiership, which lasted from 1921—1931, left a strong mark on the whole Horthy era.

As Prime Minister

His premiership is best known for a phenomenon usually called the ‘consolidation’ of the Horthy regime. When Bethlen took over, the new regime was still fragile. Hungary was recovering from the lost First World War, as well as the revolutions and Communist dictatorship, not to mention the Treaty of Trianon and the ensuing devastating territorial losses. However, the most current political crisis was the so-called ‘royal question’.

The last king of Hungary, Karl IV never officially abdicated, and thus he tried to return to the throne twice. This led to the resignation of Bethlen’s predecessor, Pál Teleki, due to his conflicted loyalty. Bethlen took a harder line on the ‘royal question’, opposing the return, and—after the brief Battle of Budaörs, in which pro-Habsburg forces were defeated—enacted the official dethronization of the Habsburgs, while simultaneously reinforcing Hungary’s status as a de jure monarchy. He also disbanded the far-right militias, which, even after the fall of the Communist regime, committed many atrocities against suspected communists, socialists, liberals, as well as random people, especially Jews. While doubling down on suppressing the communists, he made a pact with the moderate social democrats, legalizing their party. Bethlen also co-opted the non-violent factions of right-wing extremists by paying lip service to them. It is noted by some modern political scientists that the election manifesto and the government programme of the United Party diverged starkly: the former being far-right, while the latter moderate.

During the 1920s, Bethlen cut the deficit and debt of Hungary. He had the country join the League of Nations, immediately obtaining a large-sum loan from them. Bethlen used it to stabilize the budget further, raise the salaries of public employees, which led to an economic upturn. Furthermore, Bethlen utilized it to create the ‘pengő’, the new currency of Hungary. He increased public funding for health care and education, as he knew that it was necessary to invest amply into the future growth of Hungary. In doing this, his famous and revered minister of education, Kuno Klebelsberg also played a prominent role. Bethlen provided health and retirement benefits to previously excluded lower classes, however, he staunchly opposed land reform.

Therefore, to sum it up,

by the late 1920s, Bethlen stabilized Hungary both politically and economically. For the first time since the turbulent early 1910s, its GDP was increasing.

Bethlen also tried to break out of diplomatic isolation. As mentioned above, he successfully had Hungary join the League of Nations, the United Nations of the times, normalized the diplomatic relations with the former Entente powers, and drew Hungary closer to Great Britain and Italy. In 1927, Hungary and Italy signed a treaty of friendship. Bethlen also recognized Weimar Germany as one of the main allies of Hungary.

Later Years

One of the most tragic elements of Bethlen’s political career is that Hungary could not enjoy the fruits of his efforts for too long. In 1929, the Great Depression hit Hungary too. With its conservative and orthodox methods,—for instance, balancing the budget or cutting back on expenditures—his government could not handle the unleashed unemployment and poverty.

In 1931, Bethlen was forced to resign. After a short interlude, the pro-Fascist Gyula Gömbös was named premier. Bethlen, both openly, as a member of the two houses of Parliament, and behind the scenes, as an advisor to Regent Horthy, worked to undermine the corporative and authoritarian plans of Gömbös.

As the prime minister died in 1936, and the moderate conservative wing of the United Party took over again, Bethlen started to retire from politics. In 1939, he did not run for a seat in the lower house. Despite this, as a member of the upper house, he kept criticizing the country’s drift toward Nazi Germany both diplomatically, and in domestic politics. He opposed the one-sided German alliance, the so-called Jewish Laws, as well as the war itself.

During the Second World War, Bethlen unsuccessfully negotiated with Great Britain, trying to create a separate peace treaty with the Western Allies. In 1944, after the Germans occupied Hungary, Bethlen was forced into hiding. He was pursued by the Nazis, but finally, it was the communists who apprehended him.

In 1945, the Soviet authorities arrested Bethlen, and deported him to the Soviet Union. The Soviets planned to imprison Bethlen there, in order to prevent him from uniting the anti-Communist forces in Hungary. However, Bethlen could not be kept as a prisoner for long. He soon died due to his old age, probably a better fate than a prolonged Soviet prison term. He passed away on 5 October 1946 in Moscow. His body was buried in an unknown gravesite. A symbolic grave was erected in his honour in 1994 in Budapest.

Legacy

One could argue that Bethlen was very similar to Tisza regarding his political goals. They both wanted a stable and prosperous Hungary, safe from all extremes. Bethlen’s legacy, however, is still viewed as more positive and less divisive. Some leftists insist him being ‘proto-fascist’. However,

most left-leaning observers value his commitment to the fight against Nazism and authoritarianism.

When the second Orbán government erected a statue in his honour, it was received without much protest or uproar. It can be said that Bethlen is cherished by conservatives, and accepted by non-extreme leftists and liberals. A peculiar thing is that his most forceful critics are the tiny minority of the so-called ‘Hungarists’ (Hungarian National Socialists). They see him as too moderate, and an obstacle in making Hungary more right-wing, and moving it closer to Germany in the 1930s.

István Bethlen is undoubtedly one of the most characteristic politicians of the early twentieth century. Just like from Tisza, we can learn much from his resilient and hard-working attitude, as well as his politics of the ‘great consolidation’.

Related articles: