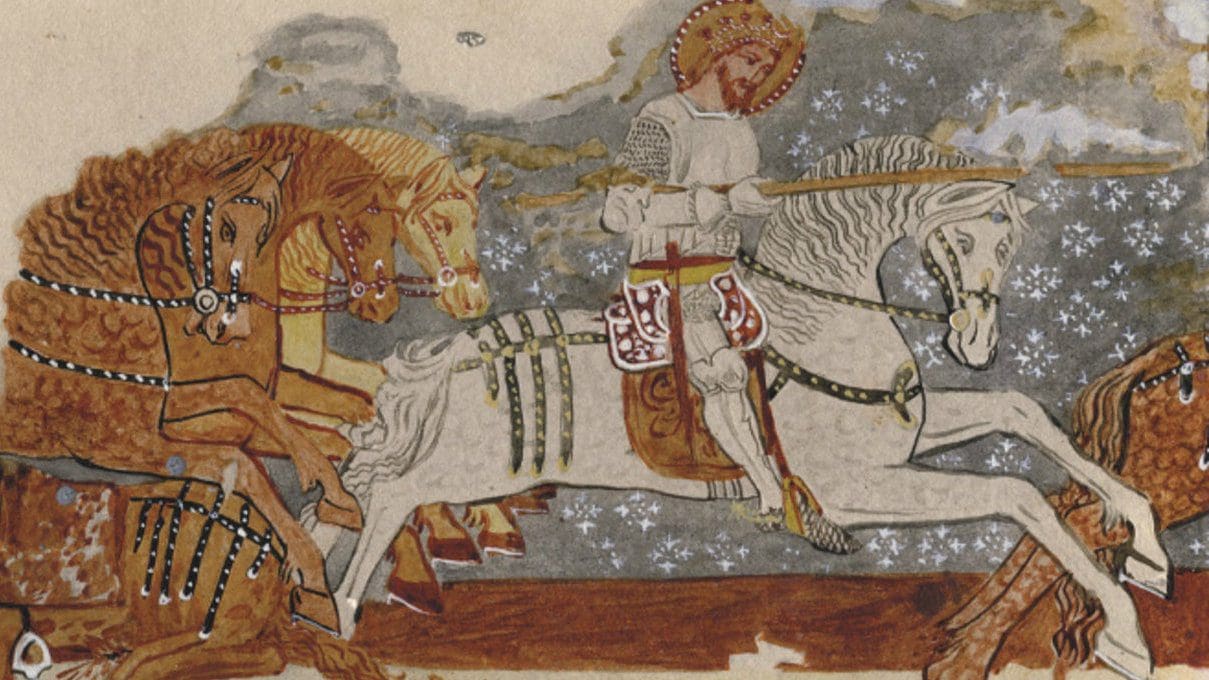

There were once two statues of Saint Ladislaus I, King of Hungary from 1077 to 1095, in the Oradea Fortress (Nagyvárad, now Romania) in Transylvania: a standing and an equestrian one. The bronze equestrian statue erected in 1390 was gilded just like all other royal statues of the time and stood on a stone base with an outstretched right hand holding a hatchet. It was one of the first outdoor equestrian statues erected after Antiquity. In 1660, the invading Ottomans destroyed the statue along with the city of Oradea, so today we can only get an idea of the quality of the late artwork from the only surviving equestrian statue of the sculptors, the Kolozsvári Brothers, which represents St George, and has been standing in Prague Castle since 1373.

At a press conference in Oradea at the beginning of 2022, it was announced that after several years of organisational work, the erection of a five-and-a-half-metre tall equestrian statue of St Ladislaus was planned for later that year. According to the latest information, the inauguration will eventually take place this year, in 2023, on the King’s feast day, 27 June, in the fortress where the statue had originally stood. If truth be told, the local Hungarian community would rather like to see it on the main square of the city.[1] The statue was completed with joint Romanian–Hungarian financing and with the support of the Hungarian State.

But why is the figure of St Ladislaus so significant in Central European historical memory?

St Ladislaus is the best-known figure of Hungarian chivalric culture. Despite the fact that knighthood in the Western sense of the word, that is as a social group, had not yet developed in the country at the time, St Ladislaus became a genuine knight king. Back then, of course, many things were communicated from the royal court to the elite of Hungarian society, and then from them to the wider circles of warriors, but the results remained selective and limited. There are almost no written sources left from this era. What we know is that historical songs did exist, but the earliest ones were about the late 15th-century victorious sieges against the Ottomans: the capture of Jajce in 1463, and Šabac in 1476.

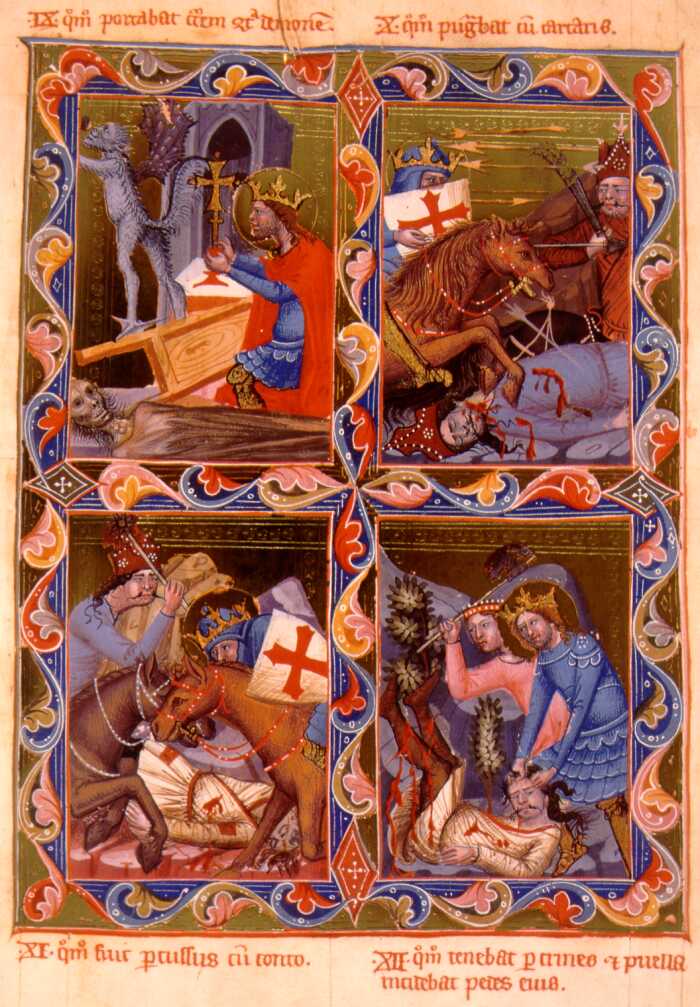

However, there are exceptions in the first centuries of 1000s: the record of the battles of King Ladislaus in the Latin translation of Hungarian chronicles and in the legends of the Saint. The King’s battles against the nomadic invaders called Cumans coming from the East can rightly be compared to the story of the Castilian knight and warlord Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar (also known as El Cid, ‘The Lord’, d. 1099) or Roland of France, a Frankish hero of the Middle Ages (d. 778). In addition to these battles, Hungarian historical memory also linked the Hungarian King to the First Crusade. According to tradition, he was asked to lead the campaign, which he accepted, but his unexpected death prevented him from completing it. At the burial place of Ladislaus, in the treasury of the Oradea Cathedral, his hatchet and silver horn were diligently guarded, indicating that the canonised king was one endowed with military virtues.[2]

In 1192, King Béla III of Hungary initiated the canonisation of his royal predecessor who was mentioned for exceptional virtues and excellence. According to a Polish historian who visited the country shortly after Ladislaus’ death, ‘he was conspicuous for his piety, as well as being tall in stature’. He also added that ‘Hungary had never had as great a king’.[3] St Ladislaus is the ruler who also achieved the greatest early ‘media success’ in Hungary—the number of murals and depictions on coins representing him exceeds that of all other Hungarian kings. If we want to recall the image of the Holy King, it is usually the wooden reliquary kept in the city of Győr, the so-called Herm of St Ladislaus, that we picture.[4] It may safely be said that, along with St Elizabeth of Hungary,

Ladislaus was the most popular Hungarian saint of the European Middle Ages.

Ladislaus first acted as a General in 1068 during his years as a prince. In that year, he went to war against the nomads invading the country and obtained a brilliant victory over them in Transylvania. The most usually represented and described part of the story is also the climax of the battle when Ladislaus saw a nomadic warrior preparing to ride away with a Hungarian girl in his saddle. He quickly followed him, and after a long struggle, he defeated and killed his opponent, rescuing the girl. The tradition of the battle acquired more details over the centuries: the kidnapping scene became the most well-known episode and one of the most depicted murals of medieval Hungarian historical literature.[5]

In Hungarian tradition, the battle had an echo far beyond its actual significance. Implicitly, King Ladislaus and the reorganisation of the country crippled in the 11th-century struggles for the throne and pagan revolts were also celebrated in this feat. ‘The nomadic warrior defeated in the battle perhaps also symbolised the past of Hungarians who had converted to Christianity, and their defeated, but still nostalgic, alter ego.’[6]

The memory of the King’s person survived in the popular imagination as well as in written sources and church traditions. From the 13th to the 15th century, the fresco cycles known as The Legend of Saint Ladislaus appeared on the walls of several of our medieval churches, especially in two areas: Transylvania and Upper Hungary. The figure of St Ladislaus is part of our history, and is still alive in the diverse areas of Hungarian cultural history.

But why did Ladislaus become the most popular of all warrior saints? It is a fact that the 12–13th centuries were clearly an era of crusader ideals and of the crusades themselves, and the persona of Ladislaus fit well into that trend. The surviving records of the battles and campaigns of the canonised King could easily be transformed by the scribes of the royal court into an image corresponding to the knightly ideal. Among the Hungarian saints, the figure of Ladislaus was the closest to soldiers, too. It is no coincidence therefore that during the Mongol invasion of 1345, many believed that the Hungarians were led to victory by a warrior appearing unexpectedly on the battlefield with a hatchet in his hand and a golden crown on his head, who was identified as the Holy King. This story was also confirmed by the testimony of the citizens of Oradea, who said that the reliquary with the Herm of Saint Ladislaus had disappeared from the Cathedral for a while, and when it returned, they found it sweating and ‘worn out by hard work’. In the Hungarian tradition, the memory of the nomads of Ladislaus’ time merged with the Mongols of the modern era, the Golden Horde and the Nogai Horde, as early as in the 14th century.

Surprisingly, the legend of the Latin Catholic St Ladislaus also appears in the 15th- and 16th-century Russian narrations

and orthodox hagiographical sources[7],[8]—it was preserved at the earliest in the compilation of Russian chronicles in Moscow, completed in 1477. According to this source, the Hungarian King led the Christian Hungarian army to victory against the Mongols and killed its leader Batu Khan. The event is described in this way even despite the fact that Ladislaus only fought against the Mongols centuries later and the death of the historical Batu Khan had nothing to do with the Mongol invasion of Hungary between 1241 and 1242 as died of natural causes around 1255. The record that served as the source of the Russian story was obviously prepared with the knowledge of the respect for Ladislaus in Hungary and the Hungarian chronicle tradition, combined with the well-known saga of the creation of the King’s equestrian statue in Oradea.

According to the Hungarian Chronicle, during the Mongol invasion, King Ladislaus stood on a high pillar in Oradea, lamenting the destruction by the Mongols and the abduction of his sister. Then, divinely inspired, he came down from the pillar and his saddled horse was already waiting for him at the foot of the pillar, carrying his hatchet. He caught up with the fleeing Batu Khan and killed him, along with his sister, who had fallen in love with the Mongol leader in the meantime. Returning from the chase, an equestrian statue representing the King was erected in Oradea to commemorate his victory over the Mongols. Compared to the Hungarian text, of course, the Russian story is a bit different: according to that version, Archbishop of the Serbian Church Saint Sava (1175–1236) first converted the Hungarian King to the Orthodox faith, and Ladislaus gained his victory only after that.

Nowadays, we talk a lot about ‘the abuse of the middle ages’—something similar could have happened in the Russian princely court at the end of the 15th century. The legend of the Hungarian Holy King, who, according to the story, was of Orthodox faith and defeated the Mongols, was very much in demand in the court of Ivan III of Moscow (r. 1462–1505). From the 15th century, Batu Khan’s role was prominent in Russian sources, as his name symbolised the enemy—just one hundred years after the legendary victory over the Mongols in the Battle of Kulikovo, Ivan the Great finally broke the shackles of Mongol dependence around this time. According to Russian legends, from 1476, the Grand Prince did not pay the taxes, then in 1480, he put the army of Akhmat, Grand Khan of the Golden Horde (r. 1465–1481), to rout, along the Ugra River. Therefore, it may not be surprising that the legend of Saint Ladislaus was also written down in the Russian chronicles around that time, and the Hungarian gold coins were copied in Moscow in the 1480s, too. In accordance with the traditional Hungarian minting practice, on one side of the coin, there is the figure of St Ladislaus with a bard in his hand, while on the other side, the Hungarian coat of arms can be found, although with the name of Ivan III inscribed in it.

St Ladislaus truly connects the nations of Central Europe: the King was born in Poland, became the patron saint of Transylvania, founded bishoprics in Oradea and Zagreb, coins with his image were minted in Russia, and his legend was copied into several chronicles around Europe. Keeping his memory alive is our common cause. As the organisers of the erection of the equestrian statue of the Holy King said in response to critical comments: ‘The legacy of St Ladislaus is above all the courageous admission of the Christian faith, which is a universal value and part of our European identity.’[9]

[1] https://24.hu/kultura/2023/02/08/szent-laszlo-var-nagyvarad-szobor-deak-arpad-lovas-szobor/, accessed 15 February 2023.

[2] Gábor Klaniczay, Holy Rulers and Blessed Princesses. Dynastic Cults in Medieval Central Europe, Cambridge, 2002, pp. 173–194.

[3] ‘The Deeds of the Princes of the Poles’, in János M. Bak (ed.), Gesta principum Polonorum, transl. Paul W. Knoll and Frank Schaer. Budapest–New York, 2003, p. 97.

[4] https://www.hungarianconservative.com/articles/culture_society/the-herm-of-saint-ladislaus/, accessed 15 February 2023.

[5] Ernő Marosi, ‘Between East and West. Medieval Representations of Saint Ladislas, King of Hungary’, The Hungarian Quarterly, Vol. 36, 1995, pp. 102–110.

[6] Gábor Klaniczay, ‘The Origins of the St Ladislas Cilut’, in Attila Zsoldos (ed.), Nagyvárad és Bihar a korai középkorban, Oradea, 2014, p. 35.

[7] Pierre Gonneau, ‘Hungary in the pages of Ivan the Terrible’s Illuminated Chronicle (1568–1576)’, in Dániel Bagi, Gábor Barabás et al. (eds.), Hungary and Hungarians in Central and East European Narrative Sources (10th–17th Centuries), Pécs, 2019, pp. 189–208.

[8] Charles J. Halperin, ‘The Defeat and Death of Batu’, in Victor Spinei and George Bilavschi (eds.), Russia and the Mongols. Slavs and the Steppe in Medieval and Early Modern Russia, Bucarest, 2007, pp. 105–119.

[9] https://kronikaonline.ro/erdelyi-hirek/az-egyhaz-es-az-onkormanyzat-osszefogasabol-valosul-meg-a-nagyvaradi-szent-laszlo-lovasszoborallitas, accessed 15 February 2023.